Sexual harassment encompasses a wide range of behaviors, from suggestive jokes and demeaning comments based on gender stereotypes, to explicit requests or demands for sexual favors, to sexual assault and other acts of physical violence. Workplace sexual harassment is illegal in the US as well as in more than 75 other countries, and is internationally condemned as a form of sex discrimination and a violation of human rights. Because sexual harassment increases absenteeism and turnover and lowers workplace productivity, it is costly to both targets of harassment and to organizations. As with other highly adverse working conditions, workers at risk of sexual harassment receive a pay premium for exposure to this despised working condition.

It would seem that the combination of legal consequences and market pressures should drive out workplace sexual harassment. Yet, more than 30 years after becoming widely recognized as a form of illegal employment discrimination and a harm to dignity, workplace sexual harassment remains pervasive. Survey evidence from 11 northern European countries shows 30–50% of women, and 10% of men, have experienced workplace sexual harassment. Evidence from the US shows similarly high rates of sexual harassment.

Prominent cases of sexual harassment dominate the news and have led to leadership shakeups at the highest levels of business and government. In 2016, Fox News CEO and chairman Roger Ailes was ousted in light of a barrage of evidence of longstanding sexual harassment against many female Fox News employees, despite formal policies, workplace training, and reporting procedures. A lawsuit filed by former Fox News host Gretchen Carlson resulted in a reported $20 million settlement.

Why is sexual harassment still a major workplace problem? There are several barriers to its eradication. Sexual harassment is challenging to define, measure, and monitor, making it hard to draft and enforce laws and workplace policies that prohibit it. Although the legal definition varies by country, sexual harassment is understood to refer to unwelcome and unreasonable sex-related conduct. But, except for sexual assault, which is always a crime, whether specific acts constitute sexual harassment in the legal sense depends on factors such as context and frequency.

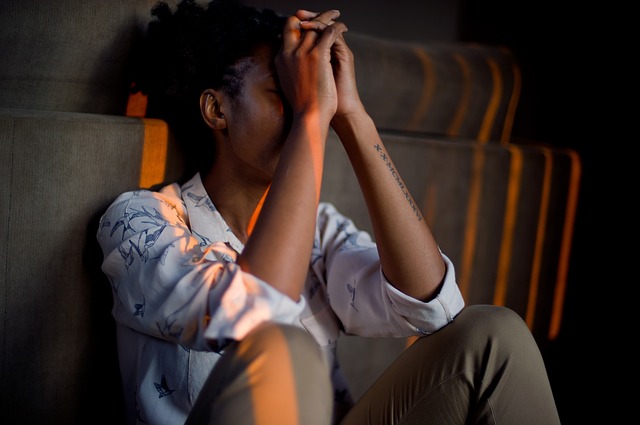

Sexual harassment is substantially underreported, in part because workers who speak out rightly fear retaliation that may put their careers at risk. Underreporting undermines enforcement efforts, as laws and workplace policies depend on reporting to identify harassers and to discourage harassment. Women face far higher risk than do men, but are also less likely to be in positions of influence that would lead to changes in workplace culture.

What can be done to reduce workplace sexual harassment? Workplace policies and training have not been adequate in protecting workers from sexual harassment. However, as the Fox News case illustrates, litigation can be effective in exposing illegal behavior. In the absence of effective workplace policies and legal protections, many victims may unfortunately find that their only recourse is to follow Donald Trump’s much-derided suggestion: When asked what his daughter should do if she is sexually harassed at work, he responded, “I would like to think she could find another career or find another company if that is the case.”

© Joni Hersch

Related article:

Sexual harassment in the workplace, by Joni Hersch

Please note:

We recognize that IZA World of Labor articles may prompt discussion and possibly controversy. Opinion pieces, such as the one above, capture ideas and debates concisely, and anchor them with real-world examples. Opinions stated here do not necessarily reflect those of the IZA.