The spread of illness is driven not only by biological factors, but also by human behavior. Within the context of a pandemic, failing to account for the role of human behavior undermines the effectiveness of policies aiming to curb the spread of illness. Tension between individual behavior and population health is not unique to the Covid-19 pandemic. HIV/AIDS provides an ongoing case study. In that context, risky sex not only affects the individual, but also contributes to the spread of the illness.

Then, as now, policies that assume full compliance when compliance is doubtful tend not to work. Scolding and shaming are unlikely to be enough. Optimal policy design must account for the incentives and constraints of different types of people.

Two features complicate the tension between private choices and public health in the current pandemic. First, policies to slow the spread place vastly unequal burdens on different segments of the population. For example, people unable to tele-work will have difficulty staying at home. Second, younger people face lower risks of serious illness, which could also undermine their willingness to stay at home.

In recent work we tried to understand the uneven burden of protective behaviors in the Covid-19 pandemic, such as hand washing, mask wearing, and social distancing. This study began as a speculative blog post predicting which types of people would face the most difficulty in complying with measures to slow the spread of the virus. The prediction was that social distancing could harm the poorest and most vulnerable members of society, raising questions about its sustainability. These speculations helped to guide a multi-country data collection effort shedding light on factors associated with self-protective behaviors. The data include information gathered from US respondents from California, Florida, New York, and Texas during the last week of March.

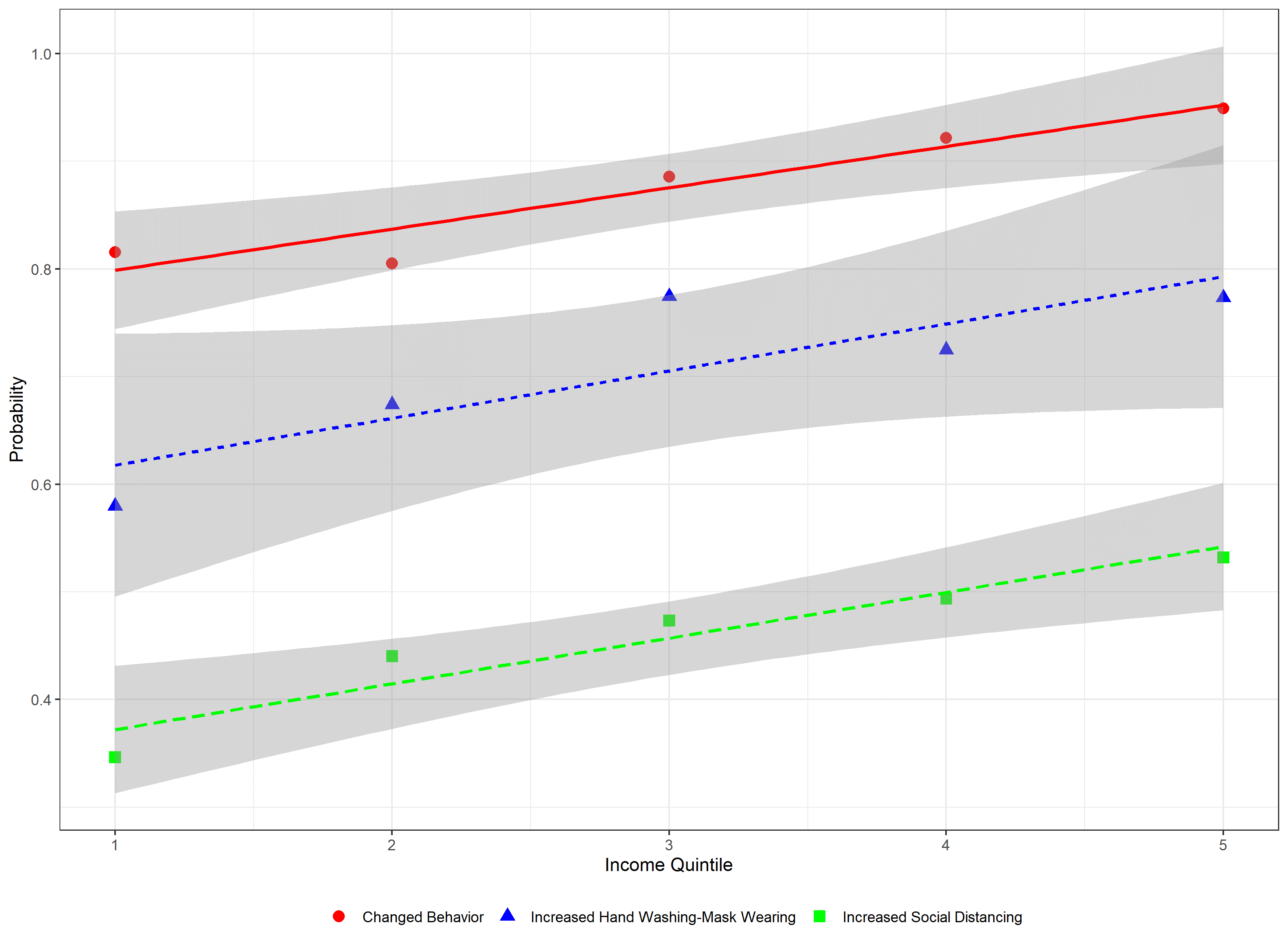

We find persistent associations between higher levels of income and increases in self-protective behaviors, as shown in Figure 1. Relative to the first income quintile, a member of the fifth income quintile is 14–28% more likely to increase social distancing behaviors and 18–28% more likely to increase hand washing or mask wearing. Work arrangements, particularly the ability to tele-work, were also found to be strongly associated with increases in protective behaviors. Relative to a person who continued to work, a person who transitioned to tele-working was 9–12% more likely to increase self-protective behaviors. Further, people without access to the open air at home were 11% less likely to practice social distancing, even after accounting for differences in income and work arrangements.

Figure 1. Probability of actions by income quintile: Proportion of respondents within an income quintile that changed behaviors, increased social distancing, or increased hand washing-mask wearing

Many socio-demographic factors were associated with decreases in protective behaviors. Respondents who were male or residents of Florida or Texas were significantly less likely to engage in social distancing. This may have contributed to current explosions of cases in those states. Additionally, white people were significantly less likely than African Americans to increase hand washing or mask wearing behaviors. This effect for increased hand washing or mask wearing is concentrated in New York and may reflect a relatively low-cost way to self-protect for people who live in densely populated areas or multi-generational housing.

To explain differences in behaviors, we also demonstrate that some people suffer more than others during the pandemic, over and above health disparities. Financial losses due to Covid-19 represent a significantly larger share of income for low income families. Expected and actual income losses for the first quintile ranged from nearly 20% to 25% while fifth quintile losses ranged from 10% to just under 15%. Low income people are less likely to have access to tele-working, contributing to higher rates of job and monetary losses. Higher income people have access to jobs that permit tele-working, helping them avoid a trade-off between their economic and personal well-being. Beyond financial losses, many people are facing difficulties stemming directly from the protective measures, making social distancing potentially unsustainable.

Policies such as social distancing are especially burdensome for some people depending on their income, housing, and work arrangements. Thus, they may be unwilling or unable to abide by them. Social scientists should work alongside health policy experts to develop humane policies that alleviate the burdens of the protective measures, making them more sustainable and less costly for larger segments of the population.

© Emma Kalish, Nicholas W. Papageorge, and Matthew Zahn

Emma Kalish is a graduate student in economics, Johns Hopkins University.

Nicholas Papageorge is the Broadus Mitchell associate professor of economics, Johns Hopkins University.

Matthew Zahn is a graduate student in economics, Johns Hopkins University.

Read more from IZA World of Labor on the coronavirus crisis.

Please note:

We recognize that IZA World of Labor articles may prompt discussion and possibly controversy. Opinion pieces, such as the one above, capture ideas and debates concisely, and anchor them with real-world examples. Opinions stated here do not necessarily reflect those of the IZA.