One of the most hotly debated issues of the current Italian electoral campaign concerns the so-called Jobs Act (JA), a wide labor market reform package introduced in 2015. The debate is centered on one specific aspect of the JA, i.e. the reduction of dismissal protection for permanent workers, implemented to alleviate segmentation between stable and temporary workers.

The new dismissal regulation predetermines the consequences for firms of a court deeming the dismissal to be unfair. In particular, it mandates that firing costs shall no longer be determined by judges, and be proportional to workers’ seniority (up to a threshold). The new rules apply to all new permanent job contracts signed after March 7, 2015 and affect firms with at least 15 employees (rules for smaller firms remained roughly unchanged, as well as rules for discriminatory dismissals).

To foster the adoption of the new rules and to stimulate job creation after a period of prolonged stagnation, the government introduced also a very generous subsidy paid to firms hiring permanent workers in 2015. The subsidy was reduced in 2016 and discontinued in 2017. Since then, the number of temporary job contracts has started rising again and the debate about the re-introduction of high levels of dismissal protection has gained new momentum.

The effectiveness of a reform cannot be assessed by simply looking at the evolution of aggregated figures (e.g. monthly employment by type of contract), since many confounding factors may be simultaneously at play (above all, the business cycle evolution, the sectoral composition of activity, structural changes in labor supply). A paper recently published in Economic Policy uses monthly administrative microdata on hires in one Italian region, Veneto, before and after the reform. Veneto is one of the most developed regions in Italy. To identify the impact of the new dismissal regulation and hiring subsidies the paper exploits some differences in their design, in particular as regards the time of their introduction (January 1 vs March 7, 2015), eligibility criteria for the subsidy and firm size, relevant for firing costs (being above vs below 15 employees).

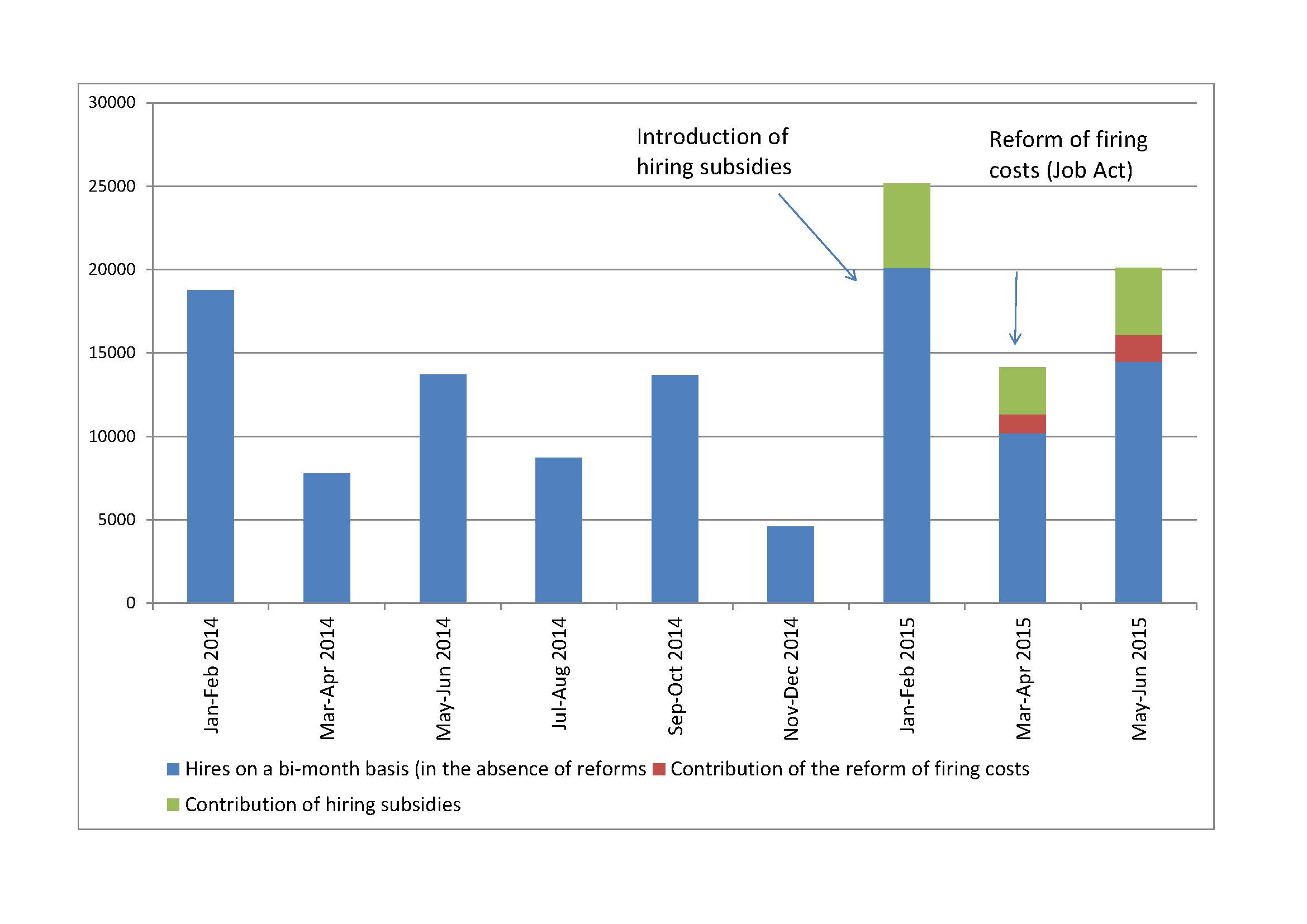

The results are reported in the figure. Each bar represents the flow of new permanent job positions before and after the reform. The colors identify the estimated contribution of the business cycle and other factors (blue part), hiring subsidies (green), and firing costs (red).

Aside from cyclical factors, hiring subsidies contributed the most to the creation of new permanent jobs (roughly 20% of new permanent hires). This is not surprising since the subsidies entailed a significant but temporary reduction of total labor cost. On top of that the JA had a non-negligible positive impact (8%).

Based on these results, the Italian debate should then focus on how to reinforce the recent reform patterns to further reduce labor market segmentation.

© Eliana Viviano

I am solely responsible for any and all errors. The views expressed herein are mine and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy.

Figure: Flows of new permanent job contracts, Veneto (number of hires, bi-monthly basis)

Please note:

We recognize that IZA World of Labor articles may prompt discussion and possibly controversy. Opinion pieces, such as the one above, capture ideas and debates concisely, and anchor them with real-world examples. Opinions stated here do not necessarily reflect those of the IZA.