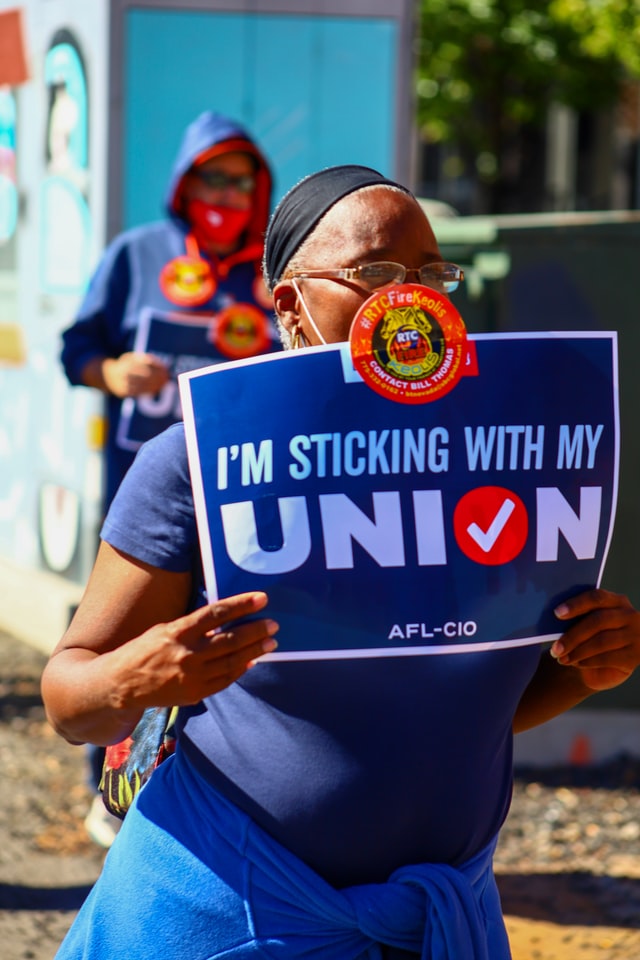

Union density has been in retreat for 50 years in most advanced nations, not least the US, where just 10.3% of workers are union members. But now it seems that unions are making a comeback. Between October 2021 and April 2022 union representation petitions in the US rose 57% from the same period a year earlier; and this is just a fraction of union organizing campaigns. Well-publicized examples are Starbucks (petitions from 250 locations after winning an election in 2021); Amazon, the second largest private employer in the nation, where workers at a warehouse in Staten Island, New York, voted to form a union in April 2022; and Google, where the Alphabet Workers Union gained its first electoral victory earlier in the year. What explains this dramatic shift in organizing activity, and does it have legs?

Covid-19 stimulated organizing in the health sector because of its obvious effects on already hard-pressed frontline workers; but similar equipment problems, abrupt changes in working conditions, and health vulnerability issues confronted many other groups of workers. Dissemination of these difficulties through digital channels has been both commonplace and a factor in facilitating worker organization. Instances of insensitive management actions were weaponized, no less than union organizing successes. Another factor was the demonstrated lower layoffs among unionized workers during the pandemic.

The tidal wave of activism may resonate with the broader public, 68% of whom now favor labor unions. Factors behind this sentiment are well-publicized (albeit contested) findings suggesting that organized labor’s decline (rather than globalization and automation) explains much of the sharp growth in wage inequality from 1973 to 2007; a belief that a spillover effect from strong unions improves the wages and benefits of non-union workers; and widespread acceptance of the argument that unions are key supporters of progressive legislation benefiting all workers. Acceptance of these views has strengthened over the pandemic.

Against this backdrop, the depiction of unions as monopolies or combinations in restraint of trade has been very much subdued recently, despite a body of research—for the US at least—pointing to modest effects of unions on productivity in conjunction with a stubbornly-high union wage premium, and negative effects on investment and R&D, among other things.

What of the future? The implications for workers and companies are not straightforward. Neither skyrocketing organizing activity nor the pronounced political shift guarantees success in reversing trends in union coverage. There have also been some notable reversals in union organizing success. The group seeking to organize Apple employees at its Atlanta store subsequently withdrew its request for an election, while in May 2022 Amazon warehouse workers at a second Staten Island location emphatically rejected a union petition. Greater organizing success by traditional unions requires changes in union strategy away from mobilization and other policies that have in the past neglected input from workers. For their part, worker-led unions do require external help, be it from traditional unions (although there is a potential problem of jurisdictional conflict), non-profit agencies, and commercial firms (most obviously in software).

If unions succeed in confronting their problems, employers should consider the current situation as profoundly different from the past. Those employers wanting to remain union-free will find the legal landscape more challenging than before, not only in expressing their view of the dangers of unionism to employees but also in their evaluation of union strength. Some will face pressures from their own shareholders: for example, Starbucks investors recently warned company leadership of the dangers of aggressively avoiding unionization, requesting it to “publicly commit to a global policy of neutrality” with Starbucks Workers United. The shareholder argument is that the company’s unique reputation would be damaged by publicity accompanying aggressive union-busting tactics. Actions such as the recent dismissal of senior managers at Amazon who presided over the landmark successful worker vote in April 2022 are unlikely to garner customer support for the brand. PR considerations are also likely to loom larger than in the past by analogy with the reaction to P&O Ferries in Britain, which summarily dismissed 786 of its crew working on British contracts issued out of Jersey and replaced them with low-wage agency staff.

Workers’ desires to unionize will depend on how well their companies listen to their concerns, which very clearly extend beyond wages. The spotlight may indeed remain on workers organizing for union representation, in which case we may expect some tangible rise in unionization. Another possibility is that more employers will come to see the value-enhancing effects of worker voice. The context here is wider than formal representation. Studies for the US have indicated that large numbers of workers report a pronounced gap between their actual say on a variety of workplace issues and what they deem to be appropriate.

Research emphatically confirms that the US is not alone in this regard. But there are different voice regimes (union and non-union) and different types of voice (both representative and direct). Surveys also reveal that no one-size shoe fits all. Some workers are likely to favor internal company solutions, others the union option. Some workers might need the defense of an independent labor union if the law inadequately protects their rights; others might need liberalization laws to enable non-union companies to expand the enhanced participation of workers. Policy should offer value-enhancing choices to the parties and the economy via multi-option systems. Heightened conflict coupled with increased experimentation in labor relations stemming from the pandemic and the political environment may yet provide markers along the path to designing a solution to the employee participation-representation gap.

© John T. Addison

Read John T. Addison's World of Labor article "The consequences of trade union power erosion," and find more curated content on unionization and collective bargaining.

John T. Addison is Research Professor and Hugh C. Lane Professor of Economic Theory Emeritus at the University of South Carolina, and a Research Fellow of IZA.

Please note:

We recognize that IZA World of Labor articles may prompt discussion and possibly controversy. Opinion pieces, such as the one above, capture ideas and debates concisely, and anchor them with real-world examples. Opinions stated here do not necessarily reflect those of the IZA.