The World Health Organization recognizes that “the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.” Despite this, disparities in access to healthcare remain a worldwide problem, often disproportionately for people of color and vulnerable populations. Even in the US, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, there are barriers that limit access to effective healthcare: a lack of providers and facilities in rural and impoverished areas, underinsurance, and financial difficulties. These deficiencies, including physician shortages and a lack of hospital capacity, were painfully revealed during the Covid-19 pandemic. The recent trend toward the centralization of healthcare compounds these concerns as many areas are becoming health deserts. For example, research found that majority African American zip codes were 67% more likely to have a primary care physician shortage than non-majority areas and rural areas have 25% fewer primary care physicians per capita than urban areas.

These challenges persist despite dramatic changes in healthcare spending and population health over the last century. Within the US, the past 100 years have witnessed a ten-fold increase in healthcare spending, a 95% decline in infant mortality, and a 45% increase in life expectancy. Moreover, healthcare now plays a central role in contemporary society accounting for nearly 20% of US economic activity, but little is known about how hospitals and modern medicine contributed to this health transition.

In a new IZA discussion paper, we study how access to hospitals and modern medicine affects short- and long-term mortality, and the long-standing Black–White mortality gap. Our study is based on a large-scale hospital modernization program introduced by The Duke Endowment in the early-twentieth century in the Carolinas. The Endowment made unprecedented healthcare investments in hospitals by building new and expanding existing facilities, obtaining state-of-the-art medical technology, and improving management practices.

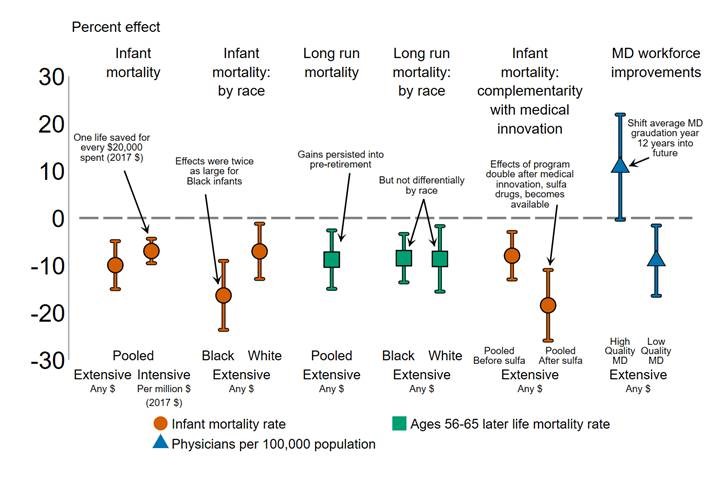

Hospital modernization improved health for those that lived nearby, reducing infant mortality by 10%. Effects were larger for Black infants (16%, 12 deaths per 1,000 births) than for White infants (7%, 4 deaths per 1,000 births), implying a reduction in the Black–White infant mortality gap by one-third. These gains were cost-effective, saving one life for every $20,000 ($ 2017) disbursed. Furthermore, investments in infancy had long-lasting effects, reducing mortality at ages 56–65 by 9%.

We find evidence supporting two important mechanisms driving these health improvements. First, modernized hospitals attracted higher quality physicians, shifting the graduation year of doctors 12 years into the future. Second, we find that the reductions in infant mortality caused by Duke support doubled after the introduction of the first effective antibiotics, implying that improvements in physical and human capital are compounded by medical innovation.

We conclude that investments in the modernization and expansion of hospitals: (i) have short- and long-term mortality benefits; (ii) have disproportionate benefits for disadvantaged groups; (iii) are cost-effective; (iv) can be particularly beneficial when implemented in under-served regions; and (v) contributed to the dramatic health improvements observed over the past century.

© Alex Hollingsworth, Krzysztof Karbownik, Melissa Thomasson, and Anthony Wray

Alex Hollingsworth is associate professor at Indiana University, USA

Krzysztof Karbownik is assistant professor of economics at Emory University, USA, and a Research Fellow of IZA.

Melissa Thomasson is professor of economics at Miami University, USA.

Anthony Wray is associate professor of economics at the University of Southern Denmark.

Please note:

We recognize that IZA World of Labor articles may prompt discussion and possibly controversy. Opinion pieces, such as the one above, capture ideas and debates concisely, and anchor them with real-world examples. Opinions stated here do not necessarily reflect those of the IZA.