Covid-19 hit a world that was unprepared for financial disruption. Before the pandemic, researchers examined balance sheets of representative households and asked a simple question: If a household totally lost its income, how long could it maintain consumption levels by relying solely on liquid wealth sources? The results showed that in developing countries, only about four in ten households could survive for a month.

The virus—and the policy measures to contain it, like lockdowns—compounded financial vulnerabilities. World Bank phone surveys in three dozen developing countries found that, on average, more than a third of respondents stopped working because of the pandemic, while nearly two-thirds of households suffered income reductions.

The need for a quick financial response to the pandemic had governments turn to digital payments. Their logic was sound. Research had found that digital payments can have a range of positive financial health outcomes, from improved risk management to women’s empowerment and reduced corruption.

Yet governments faced a conundrum: How were people with low financial capability supposed to effectively use their new digital financial tools? These concerns had some basis. A study in Colombia, for example, found that Covid-19 relief payments had positive effects on recipients’ well-being—but some people also found them difficult to use.

Fortunately, there is evidence that people learn how to use financial tools from experience. When garment workers in Bangladesh adopted direct digital wage payments, they gradually learned how to dodge fees and transact without help from an agent. At the same time, they landed higher savings and improved their financial risk management.

People also acquire financial skills from their peers. Migrant workers in Korea, for example, discovered value-maximizing remittance features that weren’t advertised and could only be learned through social networks.

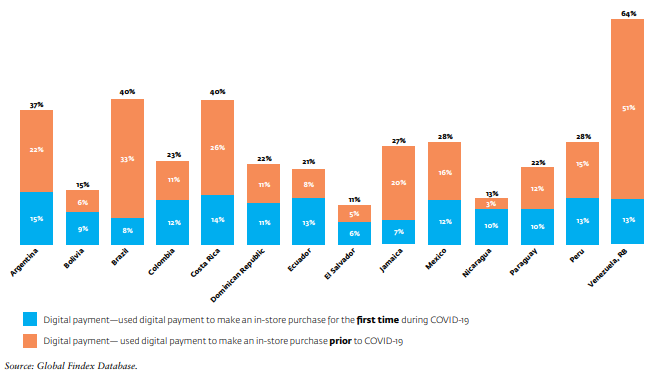

Looking back, it seems inevitable that the pandemic would trigger a surge in digital payments. People (incorrectly) thought cash would spread the virus, and they (correctly) sought to maintain social distancing while shopping. One of the most striking examples of Covid-era digital payment adoption was the abrupt shift in merchant payments from being mainly cash to more electronic forms, as the figure shows.

Many adults adopted digital merchant payments for the first time during Covid-19.

Share of adults who used a card, mobile phone, or the internet to make a payment in a store for the first time in the past year (%), 2020

About 50 million adults in Latin America and the Caribbean newly adopted in-store digital merchant payments during the pandemic’s first year, according to new World Bank data. As governments pushed out safety net payments, unbanked adults faced the choice of opening accounts or forgoing relief.

Now is the time to build resilience to the next major financial shock, especially an unusually sudden one like the Covid-19 pandemic. That response would begin by ensuring everyone has affordable, appropriate, well-regulated, and easy-to-use financial services. Consumer protection is vital for financial inclusion, especially at a time when people are newly adopting digital financial services in droves.

© Leora Klapper

Leora Klapper is a Lead Economist in the Finance and Private Sector Research Team of the Development Research Group at the World Bank and a founder of the Global Findex Database.

Please note:

We recognize that IZA World of Labor articles may prompt discussion and possibly controversy. Opinion pieces, such as the one above, capture ideas and debates concisely, and anchor them with real-world examples. Opinions stated here do not necessarily reflect those of the IZA.