Venezuela’s refugee crisis tests Peru’s economy

Peru’s federal government is currently assessing how the country’s economy and labor market can cope with the 700,000 Venezuelans who have left their ailing country for Peru in recent years.

Peru is the second most popular destination for Venezuelan migrants and refugees behind neighboring Colombia and the International Organization for Migration has estimated arrival numbers could rise to 1.4 million by the end of 2019.

Superintendent of the Ministry of Migration, Roxana del Aguila Tuesta, acknowledges “this is one crisis—a human crisis.” Stressing further, “We cannot close our eyes, close our ears or close our mouths,” to the situation.

Arrivals before October 31, 2018 were able to access a one-year temporary residency permit (the PTP) that granted access to work, education, and banking services. Both the UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration have worked with the Peruvian government to bolster the country’s migration and refugee systems, which have been struggling with the demand—processing close to 5,000 applications per day.

While Peru’s GDP grew by 6% annually from 2002 to 2013, making it one of Latin America’s fastest-growing economies, since the crisis began, World Bank figures show that growth is slowing (2.5% in 2016–2017).

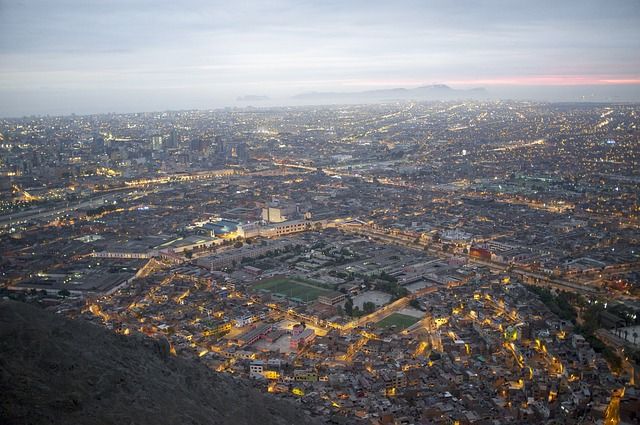

Venezuelans are also struggling to join Peru’s labor force. In Lima, Peru’s capital, where 85% of Venezuelan refugees have relocated, unemployment is 8.1%. The ILO estimates that nearly 72% of workers in Peru are in fact in the informal sector, with no guaranteed income or benefits. They estimate that less than 1% of Venezuelan migrants and refugees have found formal work.

“Immigrants are typically not evenly distributed within host countries,” says Simone Schüller in her IZA World of Labor article on immigrant economic integration, “instead they tend to cluster in particular neighborhoods.”

Policymakers are interested in how living in such ethnic enclaves may affect immigrants’ labor market integration, with fear of “ghettoization” one of the main arguments for the asylum-seeker dispersion policies implemented in many Western countries, according to Schüller.

Observations suggest that earnings may be higher for immigrants settling in ethnic enclaves, depending mainly on the quality of the co-ethnic network. Schüller concludes that “policies that encourage immigrants to settle in regions with relatively high employment rates and education levels among co-nationals may benefit their integration into the wider host-country labor market.”

With over 75% of respondents to a recent survey believing Venezuelans are taking jobs from Peruvians and pose a threat to the national economy, the Peruvian government is certainly facing a challenge.