Elevator pitch

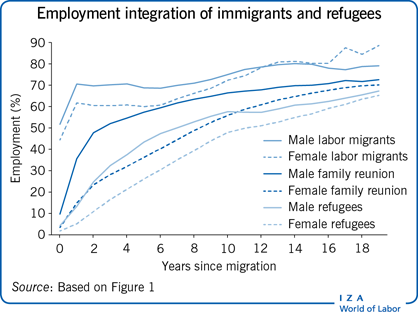

Refugee migration has increased considerably since the Second World War, and amounts to more than 50 million refugees. Only a minority of these refugees seek asylum, and even fewer resettle in developed countries. At the same time, politicians, the media, and the public are worried about a lack of economic integration. Refugees start at a lower employment and income level, but subsequently “catch up” to the level of family unification migrants. However, both refugees and family migrants do not “catch up” to the economic integration levels of labor migrants. A faster integration process would significantly benefit refugees and their new host countries.

Key findings

Pros

Refugees start at a lower employment level upon arrival in host countries but subsequently “catch up,” economically, with family reunion migrants.

Internal migration (i.e. within the host country) of immigrants in general, and of refugees in particular, is an important factor for obtaining employment.

Similar labor market results (e.g. employment and income levels) are obtained for male and female immigrants in a number of different countries.

Results from current research seem robust, since comparable outcomes are obtained when investigating various national labor markets.

Cons

Refugees integrate more slowly into host countries’ labor markets compared to labor migrants, due to not being primarily selected for host country labor markets.

Loss and depreciation of human capital and credentials during asylum procedures and lower health levels hinder refugees’ integration.

Introduction and settlement policies do not adequately help refugees attempting to integrate into the host’s labor market; this contributes to their poorer economic performance, particularly in the first few years after arrival.

Refugees’ less effective adaptation to the host country’s labor market leads to increased individual and societal costs.