Elevator pitch

The micro- and macroeconomic effects of the declining power of trade unions have been hotly debated by economists and policymakers. Nevertheless, the empirical evidence shows that the impact of the decline on economic aggregates and firm performance is not an overwhelming cause for concern. However, the association of declining union power with rising earnings inequality and a loss of direct communication between workers and firms is potentially more worrisome. This in turn raises the questions of how supportive contemporary unionism is of wage solidarity, and whether the depiction of the nonunion workplace as an authoritarian “bleak house” is more caricature than reality.

Key findings

Pros

Trade unions under certain bargaining structures can have favorable macro consequences by being less aggressive in their wage bargaining.

Trade unions can have favorable micro outcomes by stimulating worker voice.

Trade unions can facilitate contracting where there are benefits to a long-term relationship between the employer and the worker.

Trade unions have historically reduced wage inequality.

There has been a reversal of adverse union effects, where observed.

Cons

Trade union monopoly power is bad, and its exercise may lead to a misallocation of resources.

The basis of pro-productive union effects is vague while there exist alternative, non-union voice mechanisms.

Governance procedures are not exclusive to union regimes and by design may lower rent-seeking behavior injurious to firm performance.

Unions may no longer reduce wage inequality or support redistributive policies.

Reductions in union power may directly underpin a reduction in the disadvantages of unionism.

Author's main message

To the extent that unions have been found to have negative effects on net, their decline might be deemed no cause for concern. However, even in these circumstances, “on net” is not a sufficient guide for policy. Rather than a hands-off approach, the general goal should be to stimulate value-enhancing choices by firms and workers, while limiting the downside of rent-seeking.

Motivation

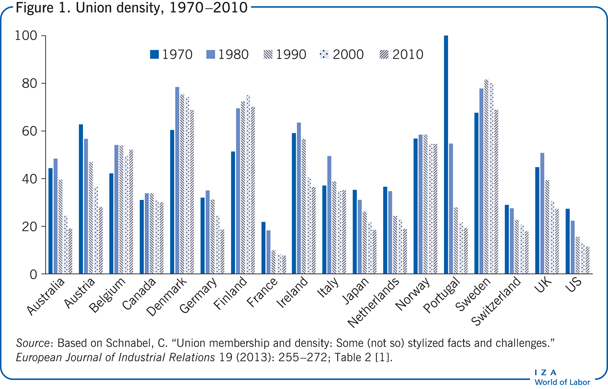

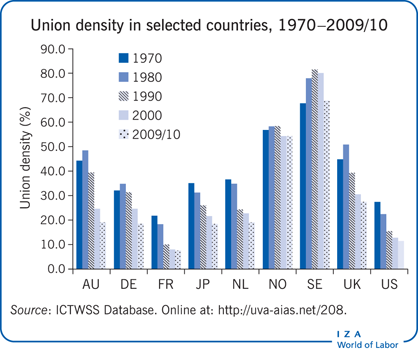

Union density is in retreat. Data for 25 advanced countries indicate that union density has fallen in 24 out of 25 countries over the last 20 years, and in 23 out of 24 countries in the last 30 years. Even if we cannot yet speak of convergence—the Nordic countries being the main outliers—there has been an unambiguous decline in unionism (see Figure 1). Sustained decline can be equated with a diminution in union power, despite pockets of union strength.

This paper discusses the consequences of this erosion along macroeconomic and microeconomic contours. Although the evidence on union effects is mixed, it can be argued that union decline may give little immediate cause for concern. Even so, two indicators typically associated with union decline—heightened earnings inequality and a potential shortfall in employee voice—occasion more concern.

Discussion of pros and cons

Collective bargaining and macroeconomic performance

In discussing the macroeconomic effects of unions, it has been conventional to draw a distinction between union membership, union coverage and bargaining structure. Union membership refers to union density, the fraction of the workforce that is organized. Union coverage refers to the fraction of the workforce that is covered by collective agreements. The latter proportion generally exceeds the former because wages negotiated by unions are often applied to non-union workers via extension agreements. Bargaining structure refers to the level at which wages are determined. It ranges from decentralized bargaining at firm level, through intermediate bargaining arrangements (agreements between industry-wide unions and employers’ associations that establish a floor of wages at the industry level), to centralized bargaining procedures (negotiations between labor and employer confederations that set national wage norms).

The three “systems” may be said to apply in Anglo-Saxon, continental European and Nordic nations, respectively, although membership and typology are in reality more fluid than this. Moreover, a given structure can mask differences in the practice of collective bargaining, such as the degree to which there is coordination in bargaining.

From the outset, union density and union coverage were associated with adverse outcomes in contrast with initially more favorable results for bargaining structure and coordination. Focusing on the latter, one important study found evidence of a non-linear relation between bargaining level and the change in employment/unemployment, as well as the Okun Index (the inflation rate plus the unemployment rate), when comparing the period 1965–1973 with 1974–1985 [2]. Others, however, reported that countries with coordinated bargaining structure experienced relatively lower equilibrium unemployment rates, although typically the fitted relation was now linear (rather than hump-shaped).

A modern review of the coordination literature, embracing the various elements of bargaining structure, examines 28 studies, which it breaks down into 174 sub-studies (where the unit of analysis is the relationship between a specific measure of bargaining coordination and an individual performance measure) [3]. Abstracting from whether the associations are linear or non-linear, on a simple head count 45% of the sub-studies support the view that coordination works—either by lowering price inflation, unemployment (or a conflation of the two), or by raising employment and productivity, among other things. But the results vary considerably by outcome indicator. Critically, the more sophisticated the estimation technique employed in the study, the more elusive the empirical relationship between bargaining coordination and economic performance.

Another result is that coordination benefits, where observed, are more likely in the 1970s and 1980s than the 1990s. Further, while initially it was thought that coordinated systems were better able to react to or otherwise absorb shocks, more recent research discounts this purported dynamic benefit, although bargaining coordination may well mitigate the harmful effect of union density on unemployment.

On balance, then, union density and union coverage are associated with unfavorable outcomes, while coordination points more to a reduction in the disadvantages of (strong) unionism than indicating a direct effect on the economic aggregates.

All this is rather thin gruel. But an interesting recent development—the contingency hypothesis—argues that the success of coordination/centralization is contingent on the governance capacity of the bargaining parties at higher levels to bind lower levels (so-called vertical coordination). This ability is captured by state-based provisions for the legal enforceability of collective agreements and a peace obligation during the validity of a collective agreement. Centralized and/or coordinated wage bargaining, so the argument runs, can only be expected to deliver the macroeconomic goods in conjunction with a high degree of bargaining governability. There is some cross-section empirical evidence favoring this contingency hypothesis in terms of lower inflation and labor costs. That said, it is not clear that governance capacity is the most important enabling factor at work here, as opposed to, say for instance, the stance of monetary policy.

But what of the Nordic model? The four main Nordics—Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland—still record high levels of union density coupled with low unemployment, low income inequality, and generally favorable productivity and unit cost development. However, despite the important role played by unions in the Nordic countries, there is little separate empirical evidence as to their specific influence (relative to other institutions) on economic performance. Also, despite its current popularity as a potential model for other countries and its use as a benchmark, the Nordic model has not always been alluring. (It will be recalled that the Nordic countries had their financial crisis in the 1990s.) There are also material differences between the individual Nordic states.

Thus, Sweden and Denmark have seen the emergence of more decentralized regimes based on more flexible wage structures than before, as well as a reordering of economic priorities. This restructuring has received insufficient attention in the economics literature. Finally, the Nordic countries are characterized by highly institutionalized social dialogues between the labor market organizations and public representatives at all levels. This privileged position of the unions in relation to public policy making and its implementation sharply differentiates this distinct bloc from most other nations.

Collective bargaining and microeconomic performance

From the perspective of micro theory, union decline again poses a mix of positive and negative elements. The conventional monopoly theory of unions sees their effects as unabashedly negative. Viewed as combinations in restraint of trade, unions introduce distortions into what would otherwise be efficient labor markets. They distort labor market outcomes owing to the increase in compensation above competitive levels, and they impose deadweight losses. To these losses in welfare, it is conventional to add the output costs stemming from the union rule-book and reduced management discretion.

But there is a countervailing face of unions that emphasizes their value-enhancing effects. The chief exponents of this collective voice view of unionism note the ambiguity introduced by long-term attachments between the firm and much of its labor force for the efficiency properties of the standard quit or exit mechanism [4]. The firm’s reliance on quits to extract information relevant to the design of an efficient mix of wages and working conditions may introduce inefficiencies by focusing on the preferences of the marginal worker rather than those of older, more stable, and potentially more valuable employees. As a result, voice or direct communication between the worker and the firm fulfils the role of bringing actual and desired conditions closer together. Crucial to this argument is that many working conditions are public goods, with the implication that they will be underprovided without some form of collective agency, at all times equated in this model with autonomous unions.

More generally, the collective voice model emphasizes the great importance of the quality of labor relations. Good labor relations are typically viewed as more likely to produce positive performance outcomes, and vice versa. Finally, the model also recognizes the shock that unions and union wages can impart to inefficient management, providing it with the incentive to tighten up on work standards and alter methods of production.

Thus, there are a number of (largely) informational channels through which unionism as the instrument of collective voice can improve the operation of the workplace, their most tangible manifestation being a reduction in quits, all things being equal. But there is also the issue of governance. Here the collective voice model is consistent with modern contract theory, wherein governance refers to the policing and/or monitoring of incomplete employment contracts.

Assuming that unions make it easier (less costly) to negotiate and administer a governance apparatus, they may be expected to facilitate long-term efficient contracting in a number of ways. Thus, a union specializing in information about the contract and in the representation of workers can prevent employers from behaving opportunistically. One fly in the ointment, however, is that the governance argument also depends on (union monopoly) power that, while necessary to make credible the employer’s ex ante promises, also gives rise to a bargaining power or hold-up problem.

Empirical evidence for the US, surveyed in an influential review, does not encourage a sanguine view of this modern perspective of unionism [5].

First, as far as the keynote productivity variable is concerned, union effects are close to zero on average, and at most modestly positive.

Second, unions have little direct effect on productivity growth; the lower growth of union firms, after controlling for union–non-union differences in capital and other factors of production, is the consequence of their being located in slower-growing sectors (but see below).

Third, the findings with respect to profitability are of concern. In one sense, a negative profitability effect is to be expected, given a substantial union wage premium in conjunction with a close-to-zero productivity effect. And virtually all US studies point to lower profitability in union regimes, irrespective of the profit measure used. At issue, however, is the source of the union gain. If the process is merely a redistributive effect, there are no implications for efficiency. But there is little to suggest that concentration-related profits are an important source of the gain. More potent sources are current earnings associated with limited foreign competition and growing firm/industry demand.

Fourth, even greater concern is occasioned by union effects on investments in tangible (i.e. investment) and intangible (research and development, or R&D) capital. US research indicates that unions capture some share of the quasi rents that make up the normal returns on investment in long-lived capital and R&D. Firms rationally seek to limit their exposure to this hold-up problem, most obviously by cutting back on these investments. There are both direct and indirect union effects: The former are caused by the union wage tax, while the latter stem from the reduction in profits (relevant because of imperfect capital markets).

Finally, lower profits and investment are manifested in lower employment growth, although infrequently in higher failure rates.

In a rare departure from these pessimistic findings, one US study examining the effects on labor productivity of various working practices, information technology, and management procedures in conjunction with unionism offers a brighter scenario [6]. Specifically, it reports that a hypothetical union plant embracing benchmarking and total quality management, with 50% of its workers meeting on a regular basis (a measure of employee involvement), and operating profit-sharing for its non-managerial employees, would have 13.5% higher labor productivity than a non-union plant with none of these practices. By contrast, the corresponding differential for a high-performance non-union plant is put at only 4.5%. An important qualification, however, is the word “hypothetical,” since such innovative union plants constitute a tiny share of union workplaces in the study sample.

To what extent do the negative US results carry over to other countries? After all, most studies confirm that the US union premium is unusually high compared with that in other countries.

Cross-country surveys do in fact often report different results for other countries. In particular, the innovation results and (to a lesser extent) the profit results are generally not found for other nations. Given that the data in these studies are rather dated, however, this section can be concluded with some updated results for Britain and Germany, along with some brief remarks on the possible variation in performance across different unionized settings.

The British case is interesting because of the shift in the impact of British unions in the 1990s and beyond compared with the 1980s. One study maps changes in the impact of British unions at a time when union density almost halved—from 53% in 1979 to 28% in 1999 [7]. It provides clear evidence of a diminution in the negative effects of unions on wages, financial performance and productivity through time. By the same token, certain other unfavorable effects of unions are shown to persist, including slower employment growth and elevated absenteeism. The study’s overall assessment that there has been a reduction in the disadvantages of unionism rather than a reversal is echoed in much of the British literature, although the evidence for profitability at least has been argued as more in line with a straight reversal of past effects.

After US and British research, union and worker representation effects on performance have perhaps been most studied for Germany. Research has focused more on works council than union effect, although recently the two have been examined together (appropriately so, given the dual system of industrial relations in that country, with collective bargaining typically being conducted at industry level and worker representation at plant level through the agency of works councils). German works councils are the exemplars of collective voice, given their statutory rights (to information, consultation, and codetermination) and constraints (they cannot bargain about terms usually fixed under collective agreements at industry level, and they cannot engage in strike action). But the breadth of their authority inevitably conveys power, and how this is exercised will determine their effects on performance. Again, theory does not provide an unambiguous answer.

Recent studies exploiting large nationally representative data sets often present a more optimistic picture than the earlier literature. Thus, there is some indication that the effect of works councils on firm productivity and even innovation may be positive if the entity is firmly embedded in the dual system (i.e. covered by a sectoral agreement). However, with the pronounced decline in unionism, German sectoral collective bargaining has significantly decentralized, and works councils have come to enjoy formal bargaining rights. The jury is still out as to whether the new bargaining role of works councils has been manifested in more active rent-seeking. In these circumstances, ambitious policy recommendations for other nations to adopt this institution may be especially premature.

Finally, as a wide-ranging British study indicated some time ago, high-performance practices are not distinctive with respect to unionism [8]. Further, the subsequent literature cannot be said to have uncovered a well-determined hierarchy for firm performance (or a blueprint for the future of unions) because of the ambiguity surrounding the costs of the practices in question, as well as profound causality issues associated with the unobserved timing of these transforming industrial relations practices.

Equity considerations: The earnings distribution and worker voice

Their redistributive function has sometimes led to unions being described as a sword of justice. Also, apart from the issue of industrial democracy, workers possess valuable private information that is more likely to be disclosed under collective action. Might not the decline in unionism therefore have worrisome implications for inequality and worker voice?

The definitive modern comparative study investigating unions and wage inequality in the US, the UK, and Canada from the early 1980s to 2001 reaches three main conclusions [9]. First, unions tend to reduce inequality in all three countries among male workers, whose union coverage tends to be concentrated in the middle of the skill distribution and whose wages tend to be compressed relative to those of non-union workers. Second, unions do not reduce wage inequality among females because (a) women, unlike men, are concentrated in the upper end of the wage distribution and (b) the union wage premium is not only greater for women but also greater for higher-skilled women. Finally, the decline in union density and the wage differential has resulted in a steady decline in the equalizing effect of unions for males but had little effect for females.

If the size of the union sector and the absence of extension mechanisms in these three countries make it much easier it to compare the structure of wages for workers whose wages are determined by union contracts and those whose wages are not, other studies have nevertheless confirmed the same basic tendencies. Thus, for example, a very recent comparative study of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations confirms that over the interval 1975–1995 countries witnessing relatively large declines in unionization also experienced relatively large increases in earnings inequality, as measured by changes in the 90:10 percentile earnings ratio [10].

After 1995, however, no such association is evident in the data. This divergence provides the starting-point for an examination of the link between changes in redistribution (measured by the percentage change in the Gini coefficient produced by taxation and income transfers) and changes in union density. A regression of the change in redistribution on the change in union density indicates a positive and statistically significant effect of unionism for the sample period 1980–1995. During this period, increasing unionism seems to have exerted pressure on governments to redistribute, and vice versa.

For the interval 1995–2010, however, the coefficient estimate for the change in union density is negative and statistically insignificant, suggesting that changes in union density were no longer linked to redistribution. By way of explanation, it is reported that union decline in many OECD nations since the 1970s has been accompanied by changes in the position of union members in the income distribution. It is conjectured that, since the average union member has become better off as union density has declined, union members have become less supportive of wage solidarity and redistributive policies. Thus, the inequality problem may remain, but the role of unions is more controversial.

This fascinating study is suggestive rather than definitive. It requires more work, as do two other issues linked to inequality that can only be raised here briefly. First, just how equalizing is equalizing once unemployment is taken into account? Second, what are the longer-term efficiency consequences of compression?

Perhaps we are on firmer ground in speaking of a shortfall of worker voice in the wake of union decline. This topic has generated much debate in the US because of (a) its vanguard position in that retreat, (b) the collective voice model, and (c) the results of large-scale surveys indicating that workers desire more voice and influence in the workplace.

Although firms in competitive labor markets may undersupply voice, it does not follow that autonomous unionism is the remedy, either from a worker perspective (where workers seek non-adversarial representation) or the practical interest of fostering higher productivity. Here a case can be made for company unionism—including non-union employee involvement/representation programs, joint plant councils, and alternative dispute resolution programs—which holds out the prospect of greater collective voice for workers without the negative monopoly effect of unionism. Legal niceties largely rule this out in the US (witness the recent Volkswagen case in Chattanooga, Tennessee), but British research suggests that employer-created non-union forms offer the prospects of meeting the aspirations of workers, and yield gains to workers and firms alike.

Indeed, the most recent research for Britain has found that the decline in union voice has been accompanied by a significant expansion in non-union voice, such that the overall coverage of voice mechanisms has remained high and stable [11]. In short, British employers have thus chosen non-union voice rather than opt for no voice at all. Moreover, comparing voice regimes, non-union voice outperforms union voice for a variety of perceived-outcome indicators—industrial relations climate, productivity, and financial performance—if not quits. This gives credence to the notion that management has an incentive to invest in non-union voice, even if this optimistic scenario is muddied by comparisons between voice types.

Limitations and gaps

Despite the wealth of evidence reviewed here, it pertains only to OECD countries and, within that firmament, the majority of studies cover Anglo-Saxon countries, whose experiences may differ in important respects from the rest. The representativeness of the results is therefore in question. Also our understanding of the relationships uncovered in the existing sample of countries is often fragile. Examples are the difficulty of measuring levels of and changes in bargaining structure, and the ambiguity surrounding transforming industrial relations practices and firm performance. Issues of causality loom particularly large. Many of the relationships examined here are descriptive and have a basis in cross-section analysis. There is a pressing need for use of better data at the micro level allowing controls for firm and worker fixed effects, in the absence of which spurious attributions of the direction of causality are all too easily made.

Summary and policy advice

Unions have both beneficial and harmful effects in theory.

Union density/coverage is associated with adverse macro outcomes, and bargaining structure/coordination no longer appears to have a direct effect on performance (although it may moderate the harmful effects associated with the former indicators). The potential of bargaining discipline awaits formal validation.

At the micro level, apart from near-universal negative findings for the US, findings for other countries are more nuanced. For its part, the British evidence points to a decline in the disadvantages of unionism rather than a simple reversal of unionism’s negative effects. The recherché notion, encountered in US and British literatures, that adopting transforming industrial relations practices enables union firms to outcompete non-union firms with the same set of practices requires validation. And while sectoral bargaining in Germany has often been criticized on macro grounds, some recent evidence suggests that that country’s dual system of industrial relations is associated with improved productivity and other outcomes.

Concern over the distributional consequences of union decline is qualified by the fact that unions are not always associated with narrowing, and the finding that changes in union density may no longer be linked to redistribution. The possibility of a diminution in voice attendant upon union decline is potentially more serious (and here US labor law is a cause for concern), although some encouraging evidence of a growth in non-union voice was provided.

The goal of policy should be to stimulate value-enhancing choices by firms and workers while limiting rent-seeking. The emphasis should be upon experimentation and self-regulation, whereby a variety of systems, including the union option, are put up for adoption by the market.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for their helpful comments on an earlier draft. The author also thanks Barry Hirsch, Stanley Siebert, and Pulkit Nigam.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© John T. Addison