Elevator pitch

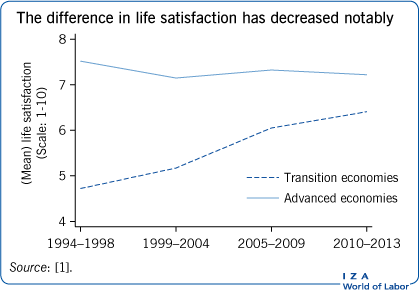

Since 1989, post-communist countries have undergone profound changes in their political, economic, and social structures and institutions. Across a range of development outcomes—in terms of the speed and success of reforms—transition is an “unhappy process.” The “happiness gap,” i.e. the difference in average happiness levels between the populations of transition and non-transition economies, is closing, but at a slower pace than the process of economic convergence. Economic growth, as the determinant of a country’s collective well-being, has been superseded by measurements of institutional quality and social development.

Key findings

Pros

The happiness gap between transition and non-transition as well as advanced countries is gradually closing.

Economic and political stability still have a stronger influence on life satisfaction than economic growth in transition countries.

Key factors to improve individual and societal well-being include perceived legitimacy of institutions, good governance, and rule of law.

High levels of social capital, in particular social trust, improve life satisfaction and happiness in the medium term, even in harsh economic conditions.

Cons

The persistence of an “unconditional” happiness gap, regardless of economic progress, suggests a permanent “negative” transition effect.

Economic convergence between transition and advanced countries may not be enough to close the happiness gap.

Dissatisfaction with life may produce reform fatigue, thus threatening the stability of new and vulnerable economic and political institutions.

Happiness gap estimates may be biased due to cultural differences across countries or generations.