Elevator pitch

Large and sudden economic and political changes, even if potentially positive, often entail enormous social and health costs. Such transitory costs are generally underestimated or neglected by incumbent governments. The mortality crisis experienced by the former communist countries of Europe—which caused ten million excess deaths from 1990 to 2000—is a good example of how the transition from a low to a high socio-economic level can generate huge social costs if it is not actively, effectively, and equitably managed from a public policy perspective.

Key findings

Pros

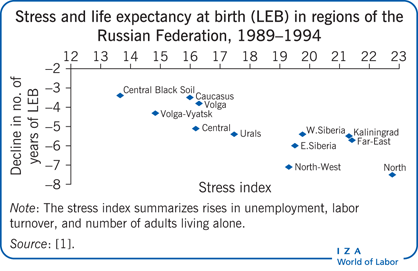

Acute psychosocial stress was one of the main drivers of the sharp mortality increase experienced by the former communist countries of Europe.

In central Europe, the post-communist mortality crisis was quickly solved, while in much of the former USSR, life expectancy at birth did not return to 1989 levels until 2013.

The relative success of central European countries in recovering from health shocks after the transition from communism indicates how this type of mortality crisis can be avoided in the future.

Cons

In most countries, analyses of the mortality impact of the transition have only had a modest impact on public policy.

The formulation of a single causal model to explain the causes of the post-communist mortality crisis is difficult because key explanatory variables belong to different disciplines.

Data on alcohol and stress during the transition away from communism are patchy at best—a fact that inhibits conclusive testing about their relative impact on mortality.

The transition mortality crisis primarily affected marginal groups such as the unemployed, single, young, and middle-aged men and women with limited education and skills, who lived in or migrated to urban areas under stressful conditions.