Elevator pitch

The Netherlands is an example of a highly institutionalized labor market that places considerable attention on equity concerns. The government and social partners (unions and industry associations) seek to adjust labor market arrangements to meet the challenges of increased international competition, stronger claims on labor market positions by women, and the growing population share of immigrants and their children. The most notable developments since 2001 are the significant rise in part-time and flexible work arrangements as well as rising inequalities.

Key findings

Pros

The employment-to-population ratio has increased from 61.1% to 65.8%.

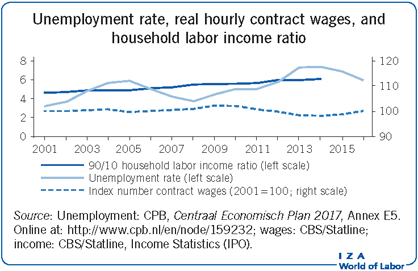

Unemployment started to fall in 2014 after a significant increase following a recession in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the euro crisis.

The Dutch labor market is highly flexible, being characterized by a large share of part-time and flexible work arrangements and labor contracts.

Cons

Labor market inequalities are growing; in particular, hourly wage inequality increased, with the 90th-to-10th percentile ratio rising from 3.0 to 3.3.

Protection of vulnerable workers has deteriorated as employers shift an increasing amount of risk onto employees.

The labor force has aged considerably, leading to lower overall labor mobility and provoking tough discussions on the pension system and the retirement age.

The labor market has faced difficulties integrating immigrants, particularly those from non-Western countries, who lag behind natives in most metrics.