Elevator pitch

The use of anonymous job applications to combat hiring discrimination is gaining attention and interest. Results from a number of field experiments in European countries (France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden are considered here) shed light on their potential to reduce some of the discriminatory barriers to hiring for minority and other disadvantaged groups. But although this approach can achieve its primary aims, there are also some cautions to consider.

Key findings

Pros

Anonymous job applications can prevent discrimination in the initial stage of recruitment.

Anonymous job applications may boost job offer rates for minority candidates.

Anonymous job applications signal a strong employer commitment to focus solely on skills and qualifications.

Standardized anonymous job application forms are an efficient implementation method.

Job applicant comparability may increase with the use of anonymous job applications.

Cons

Anonymous job applications have the potential to reduce discrimination only when discrimination is high.

Anonymous job applications may simply postpone discrimination to later in the hiring process.

The full potential of anonymous job applications can be realized only if there are no broad structural differences between applicant groups.

Suboptimal implementation of anonymous job application procedures can be costly, time-consuming, and error-prone.

Context-specific information may be interpreted disadvantageously if the candidate’s identity is unknown.

Author's main message

Anonymous job applications have the potential to remove or reduce some discriminatory hiring barriers facing applicants from minority and other disadvantaged groups. When implemented effectively, anonymous job applications level the playing field in access to jobs by shifting the focus toward skills and qualifications. Anonymous job applications should not, however, be regarded as a universal remedy that is applicable in any context or that can prevent any form of discrimination.

Motivation

Discrimination is not only unfair and potentially costly to the individuals who experience it, but also results in large economic costs for society. While discrimination exists in many markets around the world, labor market discrimination receives the most attention. A key barrier is access to jobs. Strikingly different callback rates following initial job applications have been documented for applicants from minority or other disadvantaged groups, such as immigrants and women.

But what if the characteristics identifying minority group status were unknown to recruiters? Clearly, discrimination should become impossible. Anonymous job applications put this simple and straightforward idea into practice at the initial step in the hiring process. Now that anonymous job applications have been tested in several European countries, it is possible to assess some of the potentials and limits of this new policy tool. Although it may sound counterintuitive, the underlying hypothesis is that less information may lead to better choices (and outcomes)—at least in the initial stage of the hiring process.

Discussion of pros and cons

Discrimination in the labor market takes various forms, but it appears to be more frequent in hiring than, for example, in compensation. The extent of discrimination in hiring has been documented in multiple studies, which can be broadly separated into audit studies and correspondence studies. Although audit studies, which use matched pairs of actors with identical characteristics except for one (for example, ethnicity), have long been used to document pervasive discrimination, they are criticized because applicants from different groups may not appear (otherwise) entirely identical to employers. Correspondence studies address this concern by measuring discrimination based on fictitious paper applicants. Their results are similarly persuasive, and the studies generally document substantial discrimination at the initial hiring stage in many countries, including Germany [1], Sweden [2], and the US [3].

The hiring process and discrimination

Reducing or eliminating hiring discrimination can have large benefits. Besides establishing equality of opportunity and signaling an employer’s commitment to focus solely on skills and qualifications, reducing discrimination is expected to increase diversity in the workplace. Furthermore, if recruitment decisions are based solely on skills and qualifications, the outcomes should automatically be in line with a firm’s objective to hire the most productive workers. There may be additional effects as well, for example, on the career paths and wages of workers who are potentially discriminated against.

Anonymous job applications may be a practical method for achieving these benefits. Anonymous procedures have long been used in other areas. For example, scientists have long used double-blind and single-blind procedures in experimental research studies. Blind auditions for symphony orchestras have demonstrated a strong impact on gender composition [4]. These experiences show that it is generally possible to decide or select anonymously to achieve the intended outcomes.

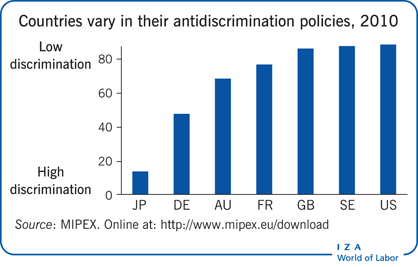

Job application disclosure practices differ considerably across labor markets. European and North American countries perform comparatively well in terms of general antidiscrimination policies and legislation (see Illustration), but this does not guarantee equality in every aspect of life. The kind of information that may legally be requested in job applications varies widely. Whereas explicitly reserving a job for a person of a certain race or gender has been illegal in the US since the 1960s, asking for very detailed personal information is standard in many Asian countries. For example, Chinese job ads are frequently segregated by gender, and South Korean application forms can include questions on such personal matters as smoking and drinking habits, height and weight, blood type, and financial status.

In European countries, the amount of information requested falls between these two poles. Although European employers would not actively ask about characteristics such as marital status or number of children, applicants sometimes volunteer such information. And information about two characteristics that are central to any debate about hiring discrimination—gender and migrant status—can often be deduced from the applicant’s name.

Expected benefits and potential shortcomings of anonymous job applications

Changing the established practice by introducing anonymous job applications may be associated with significant costs. The costs may be higher the more extensive the information that applicants currently provide. That makes finding an effective and efficient method of making applications anonymous crucial, especially from the employer’s perspective. Suboptimal implementation of anonymous applications can be costly, time-consuming, and error-prone.

Even with anonymous job applications, candidates’ identities are eventually revealed once employers have decided on which candidates to interview—at the latest, when both parties meet face to face for an interview. Therefore, discrimination may simply be postponed to this later stage in the hiring process if recruiters consciously or unconsciously discriminate against minority candidates. In that case, even though minority candidates might benefit from higher callback rates, their job offer rates would not be improved by the introduction of anonymous applications.

However, the concept of anonymous job applications relies on the assumption that prejudices play a more important role in decisions that are based solely on application documents than in decisions that are influenced by the applicant’s appearance in person. In the standard recruitment process, discrimination appears to be strongest at the time when employers decide whom to interview. Whether this assumption holds and anonymous job applications have effects beyond the first stage of the recruitment process, or whether discrimination is only postponed, requires an empirical determination.

Similarly, but slightly more subtly, structural differences in skills or qualifications between applicant groups or indirect references to a candidate’s minority group identity could still lead to discriminatory behavior in the first stage—even with anonymous job applications. In the first case, unequal education opportunities could lead to credentials that systematically vary by minority group status. Such differences in skills and qualifications could then lead to different callback rates for minority candidates even if recruiters have no direct information about the minority group status of applicants. Likewise, it may not be possible to remove all information that could point to an applicant’s minority or disadvantaged group status. For example, episodes of maternity leave are a strong signal of a candidate’s gender, while deep proficiency in a foreign language could indicate an immigration background.

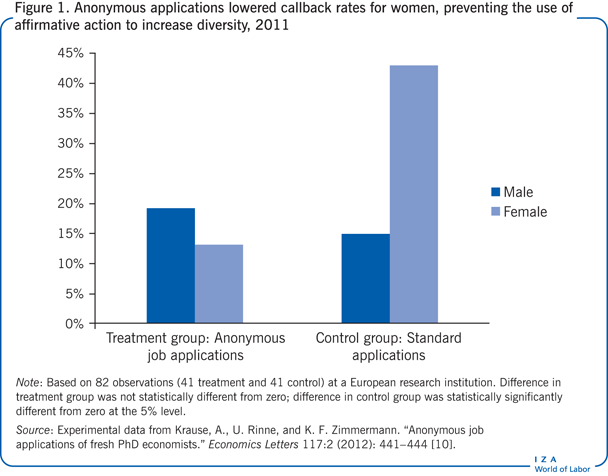

Finally, some employers might prefer to have a larger number of candidates from minority or disadvantaged groups in the initial selection stage—for example, to increase diversity in the workplace. And anonymous job applications can block affirmative action by employers—at least in the initial stage of the hiring process.

Empirical evidence and key findings

An overview of several European studies

Although the use of anonymous job applications has also been proposed in the US [5], empirical evidence on their effects is available mainly from recent field experiments in Europe (see Randomized (field) experiments). Among those that have been rigorously evaluated are large-scale experiments in France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, and a smaller-scale experiment at a European economic research institution. Small-scale implementations of anonymous applications have also been undertaken in Belgium and Switzerland, but their effects have not yet been rigorously evaluated, and hence they are not discussed here.

The French government implemented a randomized controlled experiment in the public employment service in 2010 and 2011 [6]. It involved about 1,000 firms with more than 50 employees that posted vacancies in the public employment service and that voluntarily joined the experiment.

In the experiment in Germany, which began in November 2010 and lasted for 12 months, each of the eight public and private organizations that voluntarily joined the experiment agreed to review anonymous applications in specific departments for different types of jobs [7].

In the Netherlands, two experiments were conducted in the public administration of one major Dutch city in 2006 and 2007 [8]. These experiments, which were at the department level, focused on ethnic minorities identified through foreign-sounding names.

In Sweden, results are available for two experiments. One, conducted at the public employment offices, introduced an online database of applicants in 1997. A novel feature was that applicants could voluntarily choose to exclude their names and gender from the information provided to potential employers. However, this feature might involve non-random sorting, because the job seekers who opt to hide their names and gender are very likely to be those who fear negative discrimination. In a second experiment, conducted in parts of the local administration in the city of Gothenburg during 2004–2006, anonymous job applications were introduced in some districts, while another district served as the control group [9].

Next to these relatively large-scale experiments, a smaller-scale randomized experiment provides additional insights into the effects of anonymous applications [10]. The study analyzed data for 2010–2011 at a European economic research institution on interview invitations for economists who applied for postdoctoral positions.

Findings of the European studies

Callback rates

In most of the experiments, the callback rates of minority group candidates do not differ from those of comparable majority group candidates when anonymous job applications are introduced. This is what one would expect: If application documents preserve anonymity effectively, discrimination becomes impossible.

However, the French study was an important exception to this general finding [6]. Migrants and residents of deprived neighborhoods apparently suffer from the introduction of anonymous applications: Callback rates are lower with anonymous job applications than with standard applications. An explanation for this unexpected result could be that application documents were not fully anonymous. While the applicant’s name, contact details, gender, picture, age, marital status, and number of children were not disclosed, an applicant’s residential neighborhood could be relatively easily inferred from information on schools attended, while ethnicity could be deduced from listed language skills. Whether this fully accounts for the unexpected lower callback rates for migrants and residents of deprived neighborhoods is unclear, however.

Effect of the anonymization method

Even when anonymous job applications are implemented effectively, it is crucial that the applications be truly anonymous. Otherwise, substantial costs may arise. Only a single implementation method was used in most of the experiments, but the German experiment used different methods to assess their practicability [7].

The use of a standardized application form appears to be a very efficient method—at least, once the form has been developed. Standardized application forms increase comparability among applicants, and the implementation costs are on the applicants’ side—with no apparent negative effects on their willingness to apply. In contrast, the method of blacking out information on completed applications is a particularly costly, time-consuming, and error-prone technique.

But whatever the implementation method, introducing anonymous applications forces recruiters to reconsider their recruitment practices, and their focus automatically shifts toward the applicants’ qualifications and skills.

Job offer rates

Although it seems to be generally the case that with anonymous job applications the callback rates of minority applicants do not differ from those of comparable majority applicants, this does not necessarily imply that the same holds true for job offer rates after the interview stage. Discrimination may simply be postponed to this later stage.

Although many experiments have insufficient data to assess the effects on job offer rates in an empirically sound manner, at least three studies provide some indication of these effects. First, the results of the two Swedish experiments indicate that the increased chances for minority candidates in the first stage translate into higher job offer rates. However, whereas the first experiment found higher callback rates leading to higher hiring rates across the board for minority and disadvantaged groups, the second experiment found such effects only for women and not for migrants [9].

The Dutch experiments found no differences in job offers between minority and majority candidates—regardless of whether their applications were treated anonymously [8]. This finding could indicate that, even with standard applications, discrimination against minority and disadvantaged applicants occurs predominantly when deciding about interview invitations and might not be very substantial at the job offer stage. The effects on job offer rates for women were not analyzed.

Minority groups

Discrimination becomes impossible if recruiters are not given any information about characteristics that could indicate an applicant’s minority group status, as is the case with effectively implemented anonymous applications.

However, if recruiters are able to draw indirect conclusions about race, ethnicity, or gender from the information supplied on not fully anonymous application forms, minority and other disadvantaged applicants could still face different, and in most cases lower, callback rates. Even if a way is found to make application documents fully anonymous at reasonable cost, there remains a more subtle limit to the potential of anonymous job applications.

Anonymous job applications shift the focus of hiring decisions toward the applicants’ skills and qualifications. However, if other types of discrimination in society lead to differences in skills and qualifications, anonymous applications cannot solve that problem. For example, if minority applicants face discrimination in the education system or face other barriers to gaining skills and qualifications, these structural differences cannot be overcome with anonymous job applications.

Ambiguous effects and unintended consequences

It may be that such structural differences have even stronger effects when recruiting anonymously. That is because information may be interpreted differently if the context is changed.

This appears to be the case in the French experiment with respect to information about residential neighborhood [6]. It also holds in the case of the small-scale experiment at a European research institution, where indicators of professional quality (for example, journal publications) seem to receive a different weight when screening is anonymous [10]. For example, if recruiters are not aware of the applicant’s family situation, migration background, or disadvantaged neighborhood, that information cannot be taken into account to explain such impediments as below-average education outcomes, lack of labor market experience, or insufficient language skills. The more general question is thus whether anonymous job applications remove the “signal” or the “noise” in the information that the application discloses.

The European experiments tend to show that anonymous job applications can have the desired effect of increasing the probability that minority applicants will be invited for a job interview. However, there are also some indications of the opposite effect, when anonymity prevents employers from favoring minority applicants or taking extenuating circumstances into account. That means that before introducing anonymous job applications it is crucial to identify which of three initial conditions exist: discrimination, affirmative action, or equality of opportunity. Not surprisingly, the effects of introducing anonymous applications are as different as the established practice to be changed. In the German experiment, the results were in line with each of the three initial conditions [7]. In the small-scale experiment at a European economic research institution, the use of anonymous applications blocked the desired goal of promoting the chances of the underrepresented gender through affirmative action (see Figure 1) [10]. Also, in the French experiment, as discussed above, the callback rates of migrants and residents of deprived neighborhoods were lower with anonymous applications than with standard applications [6].

These results thus corroborate the often-voiced complaint that anonymity prevents employers from favoring minority applicants when credentials are equal—at least in the initial stage of the hiring process. These circumstances may not be representative, however, as a large number of studies for many countries document substantial hiring discrimination against minority candidates. Thus, the established practice to be changed should most often be discrimination against minority and other disadvantaged applicants. In most cases, then, the use of anonymous applications should increase the probability of a job interview for minority candidates.

Limitations and gaps

Although using anonymous job applications can lead to the desired effect of increasing the chances of minority candidates receiving an interview invitation, this result does not seem to hold in every context. In general, the effects of recruiting anonymously appear to be context-specific and to depend on the established practice. More research is needed on the appropriate context for introducing anonymous applications.

Along similar lines, removing information about the identity of candidates may result in a different interpretation of other information. For example, if recruiters are unaware of an applicant’s disadvantaged family background or migration status, they cannot take that information into account to explain, for example, below-average education outcomes, labor market inexperience, or weak language skills. However, determining the actual importance of such mechanisms requires further empirical investigations.

Moreover, it is not yet clear whether using anonymous job applications has effects on the outcome of primary interest or only on the first stage of the recruitment process. Do increased callback rates of minority candidates also result in increased job offer rates? So far, field experiments have not involved a sufficiently large enough number of observations to allow significant statements to be made in this regard. And in those cases where the number of observations has been sufficiently large, the evidence on job offer rates is rather mixed and inconclusive.

Furthermore, most field experiments measuring the effects of introducing anonymous job applications focus on either the public sector or the private sector, rather than on both. And the studies that have data for both sectors do not adequately analyze whether effects differ between the two sectors. This, however, may be the case since incentives to hire minority candidates could substantially differ between the public sector and the private sector. For example, public sector employers may be rather keen on ensuring that their employees are a representative cross section of the relevant population.

Summary and policy advice

Anonymous job applications have the potential to level the recruitment playing field. If application documents are made anonymous in a way that is fully effective, the callback rates of minority applicants do not generally differ from those of comparable majority applicants. Although this is in principle a desired outcome, the relative effect depends critically on the established practice in the recruitment process and, more specifically, on the extent of discrimination that may have affected a candidate’s prospects up to that point.

Thus, current evidence does not seem to support the desirability of a mandatory introduction of anonymous job applications in every context. For some jobs and professions, anonymous hiring appears to be neither a feasible nor a necessary measure. This includes jobs in the worlds of science, the arts, and letters, since discrimination is limited in very creative, highly skilled, and rather competitive labor markets. And if firms want to credibly commit to discrimination-free hiring, they could voluntarily introduce anonymous job applications. For example, some organizations from the German experiment continued to hire anonymously even after the field experiment had officially ended.

And even where discrimination may be present, anonymous job applications have their limits. They are clearly not a universal remedy to combat any form of discrimination. They target one specific stage in the recruitment process and may have the potential to eliminate discrimination at that stage. But there are many other circumstances where discrimination against minority candidates is present that are not affected by anonymous job applications. For example, combating discrimination in education or promotions is clearly beyond the scope of this approach.

Finally, the public debate about anonymous job applications shows an interesting trend in the policy approach toward it. Many European countries have conducted field experiments to thoroughly evaluate the actual effects of anonymous job applications before initiating implementation on a larger scale. This new line of action in the spirit of “evidence-based policy making” should be utilized more often, also with respect to other possible reforms or amendments of existing laws.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. This paper draws on many fruitful discussions with co-authors of papers on anonymous job applications (see, for example, [7] and [10], and another joint paper listed under “Further reading”).

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Ulf Rinne