Elevator pitch

Ireland was hit particularly hard by the global financial crisis, with severe impacts on the labor market. The unemployment rate increased dramatically, and the labor force participation rate declined by four percentage points between 2007 and 2012. Outward migration re-emerged as a safety valve for the Irish economy, helping to moderate impacts on unemployment via a reduction in overall labor supply. As the crisis deepened, long-term unemployment escalated, creating significant policy challenges. Overall unemployment has been dropping rapidly since 2013, but remains above its pre-crisis level.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployment has been on a steep downwards trajectory since 2013.

Migration has acted as an important safety valve for the Irish economy, whereby increases in unemployment have led to rising emigration, thus alleviating the potential impact on the unemployment rate.

Labor force participation rates have stabilized after experiencing substantial falls during the crisis years.

Cons

Long-term unemployment remains a challenge and the share of very long-term unemployed (more than four years) has doubled since the crisis.

Issues around future sources of labor supply are beginning to emerge.

In terms of unemployment, young men (aged 15–24) were hit particularly hard by the recession due to their high concentration within the construction sector.

Due to a lack of comparable earnings data over time, it is not possible to present developments in earnings inequality or the gender pay gap.

Author's main message

In the early 2000s, Irish growth was fueled by a property, credit, and construction boom. The global financial crisis in 2008 shattered this growth model. Between 2007 and 2012, the unemployment rate soared from 4.7% to 14.7%, despite outward migration helping to moderate some of the impact. Recovery has been underway since 2013, but long-term unemployment and uncertainty about the future labor supply remain salient issues. Looking to the future, labor market activation programs to train the long-term unemployed for future labor market needs should be prioritized. Migration could also offer a means of alleviating growing labor supply concerns.

Motivation

As a small open economy, the business cycle is particularly pronounced in Ireland. The openness of the economy also includes the labor market, and migration has traditionally played an important role in dampening the peaks and troughs of the cycle. Although the unemployment rate rose to double-digit figures during the Great Recession, the rate would have been much higher if not for emigration. At the same time, if immigration had not taken place during the Celtic Tiger growth period, the country would have faced significant wage pressures that would have impacted the country’s competitiveness and ultimately its growth rates during this period.

Discussion of pros and cons

Aggregate issues

The past 20 years have seen the Irish economy experience an unprecedented boom and a spectacular bust. From a relatively low standard of living within the EU15 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) in the early 1990s, the following decade saw the standard of living in Ireland converge rapidly to the EU15 average. Between 1997 and 2007, real GNP expanded at an average rate of 6% per annum. The economic success of the Celtic Tiger years was mirrored by developments in the labor market. The unemployment rate fell dramatically in the 1990s, from 15% to just over 4% in the early 2000s, and substantial immigration helped to relieve labor market pressures.

Until 2000, growth was underpinned by an expansion in world trade and a rapid increase in world market share for Irish exports. However, rising incomes and Ireland’s relatively young population of household formation age (the age where people set up independent households), together with the increased availability of low-cost finance as a result of European Monetary Union (EMU) membership, led to a boom in the building and construction sector. In contrast to the 1990s, where growth was driven by exports, the housing boom was the driving force for economic growth over the following years. By around 2003 domestic savings were no longer sufficient to fund the housing boom and the banking sector continued to fund the property sector by foreign borrowing. In addition, public finances became increasingly dependent on transaction taxes in the property sector [1].

When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, Ireland was particularly exposed: this was intensified by a collapse in property prices and the construction sector, followed by severe difficulties in the banking sector [2], [3]. The contraction in economic activity was dramatic, with a cumulative fall in real GNP of over 11% in 2008 and 2009. The full gravity of the problem with the banking system was not fully realized until the autumn of 2010. The revelation of these problems saw Ireland’s access to international funding drying up. This, combined with the large fiscal deficit that emerged in the wake of the crisis, led the government to turn to the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), known as the “Troika,” in late November 2010 for assistance. Ireland exited the assistance program that was agreed with these three institutions in 2013. Recovery has been underway since then and the economy is currently one of the fastest growing in the EU.

Unemployment—Aggregate, by gender, and by age

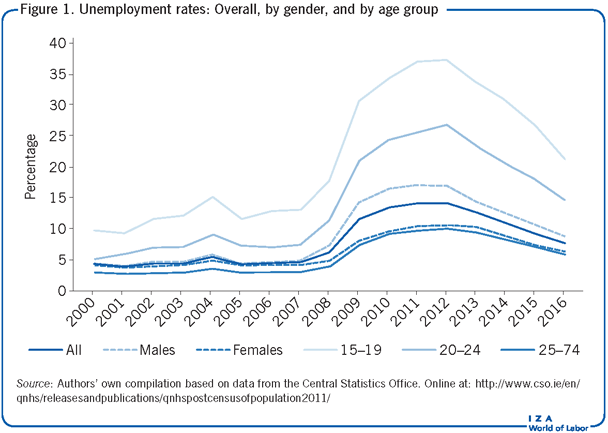

Figure 1 presents developments in Ireland’s unemployment rate between 2000 and 2016, overall and separately by gender and age. Three distinct periods can be identified: 2000−2007, 2008−2012, and 2013−2016, each of which reflect the country’s variable economic growth over the entire period.

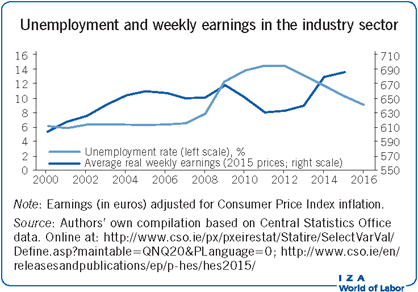

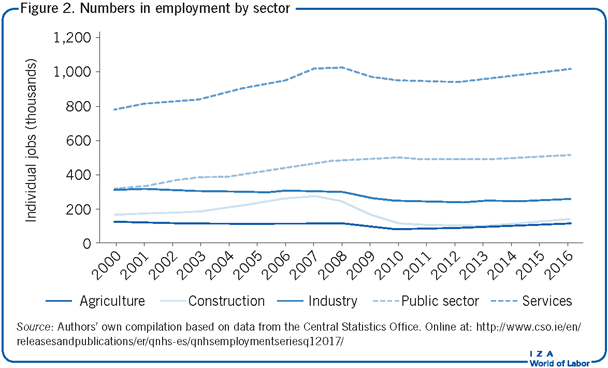

The rapid economic growth that took place in Ireland during the mid to late 1990s resulted in the country’s unemployment rate falling to a low of 3.9% in 2001, the lowest on record in modern history. Ireland’s unemployment rate remained low between 2001 and 2007, averaging 4.6%. As indicated already, Ireland’s economic expansion during this period was largely driven by the property sector. The impact that this specific type of growth had on employment in the construction and services sectors can be seen in Figure 2.

Between 2001 and 2007, the male unemployment rate (4.9%) was slightly higher than the average rate. The youth unemployment rate (ages 15−24) was, not surprisingly, above average between 2001 and 2007, particularly for those aged 15−19 years where the rate averaged 12.8%. Nevertheless, at less than 10%, Ireland’s youth unemployment rate during this period was much lower compared with the rate in some other OECD economies.

The spillover effects of the crisis on the country’s labor market were severe. As can be seen in Figure 1, the overall unemployment rate increased from 4.7% in 2007 to 14.7% in 2011−2012.

Men, in particular, were severely affected by the downturn because of their high concentration in the construction sector prior to the recession. Between 2007 and 2012, more than 162,000 construction sector jobs were lost (Figure 2), which made up more than half of all job losses over this period (303,000). This, combined with job losses in agriculture and industry, resulted in the male unemployment rate rising to 17.7% in 2012. While the female unemployment rate also rose between 2007 and 2012 (where it peaked at 11%), the increase was not as great as that for men because before the recession women were over-represented in sectors that were less exposed to the downturn [4]; in particular, health and education, which were public sector organizations that continued to expand throughout the downturn, as shown in Figure 2.

Young people were also exposed to the collapse in construction. In 2007, the construction sector accounted for 17% of employment among those younger than 25, and almost one-third of employment for men younger than 25 [4]. This, along with the concentration of their employment in other cyclically sensitive sectors, such as manufacturing and wholesale and retail, resulted in the unemployment rate of those aged 15−19 rising sharply to 39% in 2012 and to 28% for those aged 20−24. Relative to younger people, those aged 25−74 were less exposed to job losses in the construction sector and, consequently, their unemployment rate did not increase by as much over the recession: it rose from 3% in 2007 to 10% in 2012.

The Irish economy began growing again in 2010; however, the recovery was quite muted and has only gathered momentum since 2013. Since then, the unemployment rate has fallen quite rapidly: as of 2016, the overall rate stood at 7.9%. For men, the rate was 9.1% in 2016; for women it was 6.5%. Thus, the large gap that emerged between the male and female unemployment rates during the Great Recession (17.7% and 11% respectively) has closed quite considerably during the recovery period. Youth unemployment rates have also fallen during the recovery: in 2016, the rate was 22.3% for those aged 15−19 and 15.4% for those aged 20−24. However, while there has been considerable improvement in the labor market, the unemployment rate is not as low as it was before the crisis. Consequently, Ireland cannot be described as having fully recovered from the Great Recession, as the economy is not yet at or near full employment, as it was in the early 2000s.

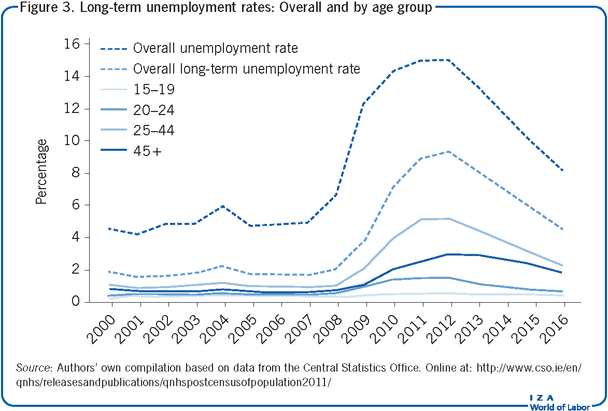

Long-term unemployment—Aggregate, by age, and by duration

Figure 3 shows long-term unemployment rates between 2000 and 2016, overall and by age group. In Ireland, long-term unemployment is defined as a period of unemployment longer than one year. The long-term unemployment rate has followed the same pattern as the overall unemployment rate during this period. The overall long-term unemployment rate averaged 1.5% between 2001 and 2007. It then increased considerably during the Great Recession, reaching a peak of 9% in 2012, and subsequently fell back to 4.2% in 2016: again, not as low as it was in the first part of the 2000s.

Interestingly, the age breakdown reveals that the long-term unemployment rate is highest among those aged 25−44. This was already the case prior to the Great Recession, but the crisis widened the gap in the long-term unemployment rates of different age groups. Specifically, in 2012 the rate was 4.9% for those aged 25−44 compared with 2.6% for those aged 45 and above. However, as of 2016, the gap has narrowed again.

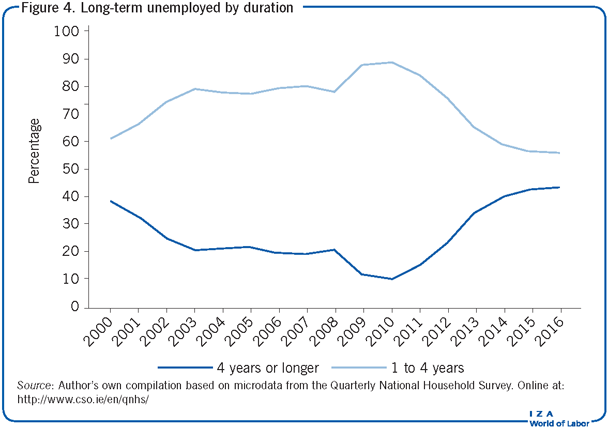

Although the economy is several years into its recovery from the Great Recession, a worrying trend emerges when examining the percentage of long-term unemployed by duration. As seen in Figure 4, the percentage of long-term unemployed who have been unemployed for four years or more has increased considerably in recent years. In 2012, the percentage stood at 23.8%. By 2016, this figure had almost doubled to 43.8%.

This is a disturbing development given the number of studies showing the negative impacts of long-term unemployment and the difficulties involved with reintegrating into the labor market after long periods out of work. Research on the characteristics of the long-term unemployed in Ireland in 2016 showed that a greater percentage are male (71%), have only a secondary school qualification or less (62%), have not worked in over eight years (42%), and that construction was the main sector where most were previously employed [5]. Some of these characteristics, such as their low levels of educational attainment, will make it even more challenging for many of the current long-term unemployed in Ireland to find jobs.

Labor force and participation developments

The gains and losses in employment and unemployment discussed above only partially shape the size and structure of the labor force. Migration and changes in participation have also been crucial to the evolution of labor supply.

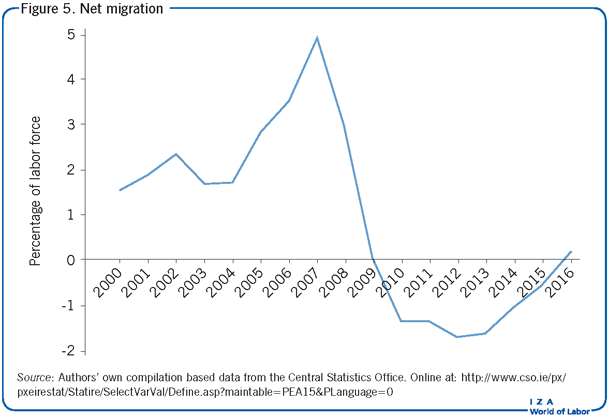

Migration flows are particularly sensitive to economic conditions. Figure 5 shows net migration as a share of the labor force from 2000 to 2016. Comparing this with the evolution of the unemployment rate shows that there is a common cyclicality between the two, with outflows tending to increase when the unemployment rate is high and vice versa. Essentially, when unemployment rises, some people decide to emigrate rather than stay in Ireland and be unemployed, thus preventing unemployment from rising further. In this sense, migration acts as a “safety valve” or an alternative to unemployment. In the second half of the 1990s, strong economic growth and a tighter labor market encouraged inflows into the country, about half of whom were non-Irish nationals. The majority of migrants during this period were highly skilled. With the enlargement of the EU in 2004 creating a much larger pool of labor, there was a further increase in net immigration into Ireland, with the bulk of the net inflow being non-Irish citizens rather than returning emigrants.

Research shows that immigrants generally earn less than comparable natives [6] and are less likely to be in high-skilled occupations [7]. Migrants were also severely affected by the crisis. A study from 2012 shows that employment among immigrants fell by 20% between 2008 and 2009, compared with 7% for natives [8]. The study also finds that this was not just a construction-industry effect; job losses were relatively higher for immigrants across most sectors. The Great Recession led to a reversal of net immigration of both Irish nationals and non-nationals starting in 2010. Following the partial recovery of the Irish economy, net emigration rates began to decline in 2013; by 2016 there was again a small amount of net immigration.

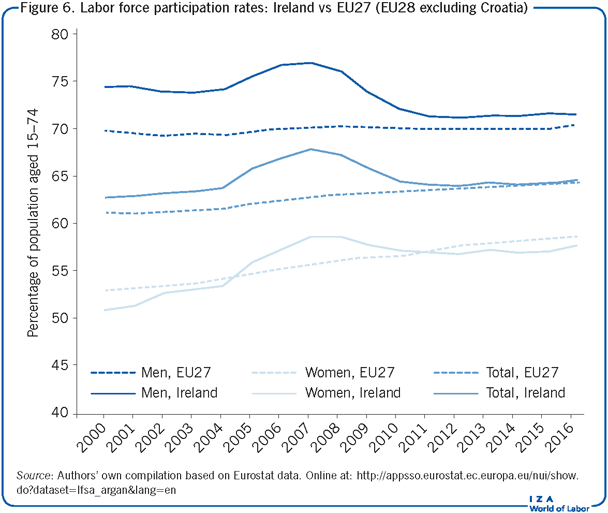

Figure 6 shows the overall labor force participation rate and separately by gender for Ireland and the EU27 (EU28 excluding Croatia). Substantial net immigration, especially in the years immediately before the crisis, led to the overall participation rate exceeding the EU27 average. In the 1980s, Ireland’s female labor force participation rates were among the lowest in the EU. However, factors such as rising educational attainment and more favorable labor market conditions led to the female participation rate rising by around one-third over the course of the 1990s. In the early 2000s, the overall female participation rate converged toward the EU average and even surpassed it in the years before the crisis. In the wake of the crisis, participation rates fell, particularly for men and younger people, in line with the severe job losses in construction. Many of the younger people who exited the labor force and stayed in Ireland returned to education [9]. In recent years participation rates have stabilized.

Looking to the future, in the context of a rapidly growing economy with unemployment on a strong downwards trajectory, issues about potential sources of labor supply are becoming more prevalent. The aggregate labor force participation rate is currently at the EU average, while the female participation rate is below that of the EU. Issues related to affordable childcare are important considerations when designing policy to further increase the female labor force participation rate. Immigration offers another possibility to increase Ireland’s labor supply, but research shows that migrants suffer penalties in the labor market. Although Brexit constitutes a challenge for Ireland, there is the possibility that it may lead to a diversion of future EU migrants who might otherwise have gone to the UK, causing them to migrate to other EU countries instead, including Ireland.

Limitations and gaps

The biggest limitation in examining developments in the Irish labor market between 2000 and 2016 is the absence of a consistent earnings series. The Irish Labour Force Survey only contains income data from 2009 onwards, and is available for employees only. A number of other earnings series collected by Ireland’s national statistical collection agency, the Central Statistics Office (CSO), were discontinued just prior to the Great Recession. In 2017, the CSO produced a new historical earnings series covering the period 1938−2015. However, this publication is based on earnings surveys that have changed over the years and, consequently, the earnings data are not directly comparable due to methodological, definitional, and classification differences.

As such, researchers are unable to present developments in the economic well-being of employees over time, including changes in earnings inequality and the gender pay gap. It is also not feasible to examine developments in entrepreneurship and start-ups because either the data do not exist or are not available for the complete 2000−2016 time period.

Summary and policy advice

After a period of incredible growth, the Great Recession rocked Ireland’s economy. Unemployment rates rose dramatically, with younger men being hit hardest by the collapsing construction sector. Net migration flipped from positive to negative during the recession, which helped moderate the size of the unemployment pool via reductions in labor supply. Since 2013, the economy has recovered considerably, though it is still not back to pre-crisis levels. Looking ahead, two major challenges seem most pertinent given the current state of the Irish labor market: long-term unemployment and future sources of labor supply.

Both Irish and international research show that active labor market programs that are closely linked to the labor market, such as training in specific skills and employment experience in private sector firms, have been found to be effective in helping unemployed individuals return to employment. Less well researched, however, is the effectiveness of programs designed to assist the long-term unemployed with their return to employment. Thus, while Irish policymakers have made considerable progress in reducing the country’s overall unemployment rate since the Great Recession, getting the very long-term unemployed back to work remains a herculean task. In parallel to this challenge, issues related to future sources of labor supply are beginning to emerge as the economy continues to experience rapid growth.

While these two issues may seem somewhat complimentary, in that policymakers could provide training to the long-term unemployed in areas where future growth is expected, this approach is likely to take a considerable amount of time. Thus, in the shorter term, migration, whether enticing those who emigrated away during the Great Recession to return or attracting new immigrants, is likely to offer a more flexible option to policymakers in dealing with Ireland’s future labor supply challenge.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the authors contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [4], [5], [7], [8].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Adele Bergin and Elish Kelly