Elevator pitch

Many countries are reviewing immigration policy, focusing on wage and employment effects for workers whose jobs may be threatened by immigration. Less attention is given to effects on prices of goods and services. The effect on childcare prices is particularly relevant to policies for dealing with the gender pay gap and below-replacement fertility rates, both thought to be affected by the difficulty of combining work and family. New research suggests immigration lowers the cost of household services and high-skilled women respond by working more or having more children.

Key findings

Pros

Immigrant inflows are associated with reductions in the cost of childcare and other household services.

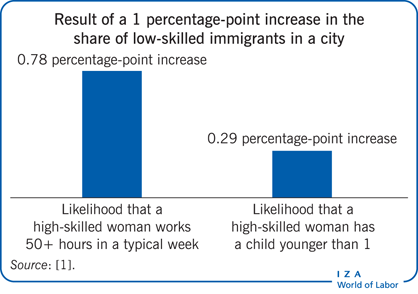

Highly educated native-born women respond by increasing their labor supply, potentially allowing them to work longer hours.

Low-skilled immigrants may bring fiscal benefits as their household services are taxed (unlike the home production they replace) and since married high-skilled women are usually subject to high marginal tax rates.

Some women have additional children in response to increased immigrant inflows, benefiting countries with declining fertility rates.

Cons

Household services workers receive lower wages as a result of immigrant inflows.

Although immigration is not associated with a decline in mothers’ time devoted to children’s educational and recreational activities, less time is spent on basic childcare tasks.

Social services for any spouses, children, and parents who come with immigrants who provide household services can be expensive.

In response to improved childcare options, women’s career success may decline when they have more children and devote less time to their careers.