Elevator pitch

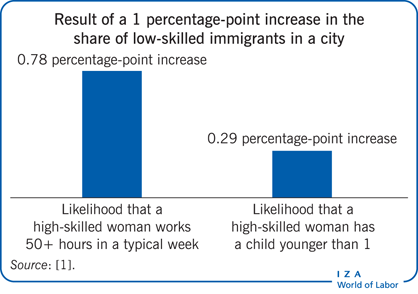

Many countries are reviewing immigration policy, focusing on wage and employment effects for workers whose jobs may be threatened by immigration. Less attention is given to effects on prices of goods and services. The effect on childcare prices is particularly relevant to policies for dealing with the gender pay gap and below-replacement fertility rates, both thought to be affected by the difficulty of combining work and family. New research suggests immigration lowers the cost of household services and high-skilled women respond by working more or having more children.

Key findings

Pros

Immigrant inflows are associated with reductions in the cost of childcare and other household services.

Highly educated native-born women respond by increasing their labor supply, potentially allowing them to work longer hours.

Low-skilled immigrants may bring fiscal benefits as their household services are taxed (unlike the home production they replace) and since married high-skilled women are usually subject to high marginal tax rates.

Some women have additional children in response to increased immigrant inflows, benefiting countries with declining fertility rates.

Cons

Household services workers receive lower wages as a result of immigrant inflows.

Although immigration is not associated with a decline in mothers’ time devoted to children’s educational and recreational activities, less time is spent on basic childcare tasks.

Social services for any spouses, children, and parents who come with immigrants who provide household services can be expensive.

In response to improved childcare options, women’s career success may decline when they have more children and devote less time to their careers.

Author's main message

In many countries with large immigrant inflows, childcare and household services become more available and costs fall. That can free high-skilled women to increase their labor supply and may induce them to have more children. Women can thus devote more time to their careers, potentially reducing gender pay gaps. This impact may be weakened, however, if having more children leads women to spend less time on their careers. Policymakers concerned about low fertility rates and gender earnings gaps may consider subsidizing childcare. To defray some of the cost, visas could be targeted to childcare workers.

Motivation

Recent decades have seen unprecedented increases in international migration flows worldwide. Not surprising, given the large and growing numbers of immigrants in many countries, there is considerable debate about the labor market effects of immigration, specifically about the effects of low-skilled immigrants. Using US data, some studies find negligible negative impacts of immigration on average native wages while others find larger but still small negative impacts (see [2] for a review). More recent analyses find increases in the average wages of native-born workers, which reflect both large positive impacts on high-skilled native workers and small negative impacts on low-skilled workers. Earlier immigrants are the only group to experience substantial negative wage effects as a result of the arrival of new immigrants [2].

Although the average wage effects of immigration are small or even positive, immigrant inflows may result in large wage reductions in specific industries that employ mainly immigrants and where replacing labor with machines or moving production abroad is difficult. Two such industries are childcare and housekeeping. In addition to any wage effects, the increase in immigrant labor supplied to household industries may result in more conveniently provided services or potentially better quality care. For example, immigrant nannies may be able to watch children into the late evening and on weekends with little advance notice, while childcare centers typically close at a set time in the early evening and are only open on weekdays. Changes in household services markets may offer an avenue through which low-skilled immigrants benefit high-skilled native-born workers. Specifically, high-skilled native-born women may respond to low-skilled immigration by increasing their labor supply or fertility.

Discussion of pros and cons

Immigration’s impact on childcare and household services markets

The first step in examining whether immigrant inflows are likely to affect women’s wages and their labor-market decisions through their impact on household services markets is to test whether employment shares and wages in these occupations change with the share of immigrant labor. After all, if immigrants do not affect childcare and household services markets, then they surely cannot affect women’s work and family decisions through childcare channels.

Intuitively, an increase in the supply of workers in a specific market should lower wages and increase employment in this market. However, the size of these impacts depends on how responsive employers are to changes in the wages they must pay their workers. If new technologies can easily substitute for workers, wages will not be very sensitive to immigrant inflows. For example, in cities with few low-skilled workers, where wages are likely to be high, grocery stores might invest in self-checkout machines. If the situation changes because of large immigrant inflows, grocery stores may use fewer of these machines. As a result, the average wages of grocery store workers might not change very much in response to immigrant inflows. In the same way, if jobs can be easily offshored, then increases in the number of immigrants will not lower wages. Childcare and other household services are industries where such substitutions are particularly difficult to make, and so wages in these industries are likely to be very sensitive to immigration.

One way to examine the impact of immigration is to compare wages and employment in areas (typically, metropolitan areas) with large immigrant populations with areas with small immigrant populations. If childcare wages are lower in areas with more immigrants, this might be taken as evidence that immigrant inflows are causing wages to drop. A problem with this methodology is that immigrants are attracted to cities with higher wages. Thus, there may be a positive correlation between the share of foreign-born workers and wages in an area even if the true causal relationship between increased immigration and wages is negative. Researchers generally deal with this issue by examining changes within a city over time. Are large inflows of immigrants into a city associated with decreases, or smaller increases, in the wages of childcare workers in that city over time?

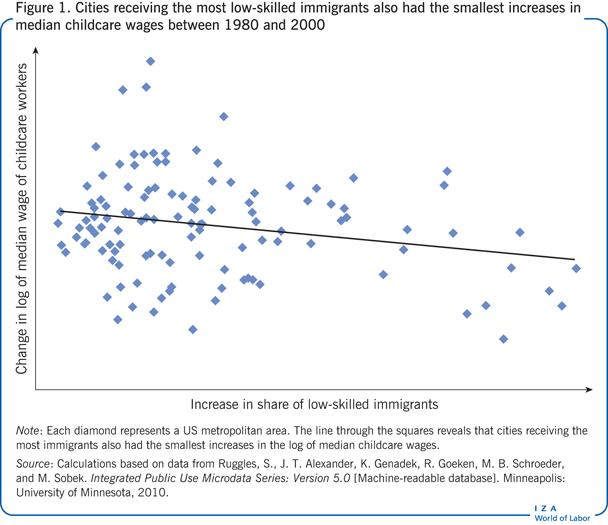

To illustrate this general approach, Figure 1 shows the relationship between changes in the share of low-skilled immigrants and changes in the log of median childcare wages in metropolitan areas of the US. Each diamond represents a metropolitan area. The line through the squares reveals that cities receiving the most immigrants between 1980 and 2000 also had the smallest increases in median childcare wages.

A problem remains with this approach if immigrants choose where to live based on expected future growth rates of wages of childcare workers or of low-skill workers in general. If so, that would imply that the true causal relationship between immigrant inflows and childcare wages is even more negative than Figure 1 suggests. To address this issue, researchers typically use an instrumental variables technique, which takes advantage of the fact that while part of an immigrant’s location decision is based on actual or perceived economic opportunities, another part may be based on where it is easiest to live. In particular, immigrants are drawn to cities where there is already an established community of people who share the same ethnic origin. In these communities, it is easier for new immigrants to communicate with others in their native language, dine at ethnic restaurants, and attend ethnic festivals. Using historical residential patterns of immigrants from different groups along with information on the flows of immigrants from different countries to the US, researchers are able to predict immigrant populations in different cities on the basis of the tendency of immigrants to move to ethnic enclaves—rather than the tendency to move to better labor markets. The studies discussed below use this technique to isolate the causal effects of immigration.

Analyses of data for Spain show that, in general, a one percentage-point increase in the share of female immigrants in a region is associated with a 3.2% drop in household services wages [3]. After controlling for the fact that immigrants are attracted to areas with higher wages, analysis shows that the same increase in immigration yields a 5.9% drop in wages [3]. Using a similar empirical approach with data for Italy, researchers have also uncovered a smaller but still negative impact of immigration on the prices of domestic services [4]. An analysis of US data looks at the impact of immigration on several household services occupations. Results suggest strong negative impacts on the wages of childcare workers and weaker but still negative impacts on the wages of housekeepers and food preparation workers. As might be expected, an increase in low-skilled immigration has the strongest effects on wages at the bottom of the wage distribution and the weakest effects at the top, but immigration lowers wages even at the 75th percentile of the childcare wage distribution [1]. All of these studies also find increases in employment in the household services sectors, but the impacts are not always significant.

Women’s labor supply responses to immigrant inflows

It is unclear exactly how women are expected to respond to a decline in the prices of household services. Certainly, women whose wages are low relative to the wages of household workers are not likely to use these services regardless of price and so will not change their behavior in response to changes in these markets. Women strongly devoted to their role as homemakers and only weakly attached to the labor market are also unlikely to make much use of market-provided household services.

Even among women who are likely to employ immigrant nannies and housekeepers, the theoretical impact of lower prices and potentially more convenient services is unclear. For example, reduced childcare costs increase the net returns of labor market work. Time spent away from work becomes relatively more expensive, and so women should respond by working more. On the other hand, it is also possible that with the money saved in childcare costs, women can afford to spend more time on leisure activities. This would imply that women work less in response to a decrease in childcare costs. Another issue is whether women respond to reduced childcare costs by having more children. If they do, then it is possible that women will reduce their labor supply, at least temporarily after giving birth. Thus, determining the real effect of immigrant inflows on women’s work decisions requires analyzing the data.

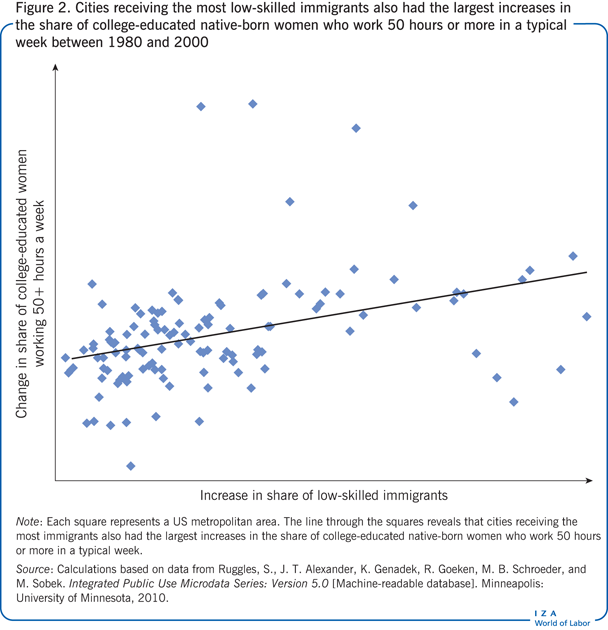

Figure 2 illustrates the general relationship between immigrant inflows and the likelihood that college-educated native women work long hours. Again, each square represents a US city. The line through the squares shows that cities with the largest inflows of low-skilled immigrants between 1980 and 2000 also had the largest increases in the share of college-educated native-born women who work 50 hours or more in a typical week. While certainly informative, this simple relationship may reflect other changes in cities that affect both immigrant share and labor supply of high-skilled native-born women. For this reason, the statistical technique discussed above that uses ethnic enclaves is typically employed in these studies.

Using US census data, the first careful analysis of the relationship between low-skilled immigration and women’s decisions on time use uncovered substantial increases in the number of hours worked by women at the top of the female wage distribution. It also found smaller but still positive effects for working women with wages above the median, but no effects for women earning wages below the median [5]. This makes sense in that women with higher wages are more likely to purchase household services. Another reason to focus on high-skilled women is that they are unlikely to compete with low-skilled immigrant workers for jobs in the labor market. Thus, any effects are more likely to operate through the household services channel. The study finds that while men also increase their labor supply in response to immigrant inflows, the impacts are much stronger for women, most likely because women bear most of the responsibility for childcare and housework. Additional analyses of time-use data suggest that women at the top of the wage distribution spend less time on household chores in response to immigrant inflows [5]. Expenditure data reveal that women are also more likely to purchase household services in response to increased immigration [5].

These general results are not specific to the US. Studies using data for Spain and Italy reach similar conclusions despite the more traditional gender norms in these southern European countries. In Spain, large recent immigrant inflows account for one-third of the increase in labor supply of college-educated women with childcare or eldercare responsibilities [3]. In Italy, moving from an area at the 25th percentile of immigrant concentration to one at the top 75th percentile results in an increase of 50 minutes per week in the number of hours women work [4]. A comparison of harmonized data for Australia, Germany, Switzerland, the UK, and the US shows a positive effect of immigrant concentration on the number of hours worked but not on the share of skilled native-born women in the workforce [6]. This effect appears to be stronger for countries with less supportive family policies.

All of these studies use the same ethnic enclave-based instrumental variables strategy to address the possibility that immigrants may be attracted to cities where native-born women already work long hours because there may be more jobs for them in these cities. Taking a different approach, researchers have also found a link between foreign-born domestic workers and the labor supply decisions of highly educated native-born women in Hong Kong [7]. In the late 1970s, a policy change resulted in large increases in the number of foreign-born domestic workers allowed into Hong Kong. To analyze the impact of the policy, researchers compared the labor supply decisions of women in Hong Kong and in Taiwan (a country very similar to Hong Kong but without the policy change) before and after the change, depending on whether these women had older or younger children, with women with younger children assumed to be more responsive to increases in the number of foreign-born domestic workers. Results suggest that the foreign worker program in Hong Kong was associated with an increases in the labor supply of medium- and high-skilled female workers [7]. A similar analysis using data from Singapore also shows that a relaxation of immigration legislation led to strong increases in female labor supply during the 1970s [8].

All of the studies mentioned here consider the effect of immigrant inflows on native-born women’s decisions rather than directly measuring the impact of having a domestic worker in the household. A simple examination of the relationship between domestic workers in the household and women’s hours of work is not very informative because the native-born women who hire domestic workers are likely to be women who work long hours regardless of whether they have domestic help. However, in Hong Kong, a peculiarity of the housing market has allowed researchers to measure the causal effect of foreign domestic workers. Hong Kong’s housing market is so tight that the number of rooms in a house can, for all intents and purposes, be considered random, or at least uncorrelated with a woman’s work preferences. That said, the existence of a spare bedroom makes hiring a live-in domestic worker much easier. Using number of rooms in a house as a source of variation in whether families have a domestic worker, researchers are able to determine whether foreign domestic workers directly affect women’s decisions of whether and how much to work. Results suggest that they do [7]. This body of work, conducted in different contexts and using several empirical approaches, points in one clear direction: immigrant-induced decreases in the price and increases in the availability of domestic services result in increases in female labor supply, specifically that of high-skilled women.

Does fertility also respond to immigrant flows?

While there is rather strong evidence that immigrant inflows tend to increase the labor supply of high-skilled women in general, it is still possible that certain women—specifically women of childbearing age—respond to immigrant-induced changes in childcare costs by having more children rather than by working more hours. New research has uncovered an increased tendency for college-educated women to bear children in response to immigrant inflows [1].

The impacts are strongest among women whose fertility decisions are the most likely to be affected by changes in childcare markets. Specifically, results are driven by married women; unmarried women’s fertility is almost unaffected by immigrant inflows. Also, women with graduate degrees are more likely than women with only a college degree to respond to immigration by having an additional child. This makes sense in that highly educated women are more likely to use market-provided childcare.

Together with the labor supply results, these findings imply that while the predominant impact of low-skilled immigration is to increase the labor supply of high-skilled native-born women, some women respond by having an additional child. These women may, at least temporarily, exit the labor force. Regardless of whether women respond to less expensive and more convenient childcare options by working more or having an additional child, the trade-offs they face for either decision should unambiguously decrease.

An often-used measure of these tradeoffs is the correlation between female labor force participation and fertility rates. Considering the time-intensive nature of working and of raising children, it should not be surprising that analyses within individual countries typically find a negative correlation between these two variables. Research has shown, however, that immigrant inflows into a city weaken this negative relationship [9]. This lessening of the negative correlation between female labor force participation and fertility rates can explain about a quarter of the recent increases in the immigration-induced rise in the joint likelihood of childbearing and labor force participation among college-educated women in the US [10]. All of these studies suggest that better childcare options, at least the immigration-induced better options, allow women to more easily combine their roles as workers and mothers.

What happens to the amount and quality of care provided by mothers?

While low-skilled immigration may make it easier for high-skilled native-born women to achieve their career and family-size goals, a natural question is whether the quality of care provided to children suffers. It is difficult to even conceptually measure quality of care, but researchers have examined the impacts of immigrant inflows on how mothers spend time with their children. They find that mothers in areas with increased immigration spend less time overall with their children [11]. A more detailed examination of the specific uses of mothers’ time shows that immigrant inflows result in large declines in the amount of time mothers spend on basic childcare activities, such as feeding and changing diapers, but no change in the amount of time they spend on educational activities with their children.

All in all, this literature provides evidence that increased immigration does have important effects on the family and time-use decisions of high-skilled women. Immigration is associated with increases in labor supply, and there is evidence that some women respond to immigrant inflows with increases in fertility. It may not be surprising that mothers spend less time with their children when household services become less expensive, but the evidence suggests that women have not sacrificed time spent on stimulating educational and recreational activities.

Limitations and gaps

As discussed, a problem with any analysis of the impact of immigrant inflows on native-born women is that immigrants’ residential decisions may be based on factors that influence native-born women for reasons unrelated to the immigrants themselves. Immigrants may be attracted to cities with booming economies in general, but specifically to cities where demand for childcare and housekeeping services is higher. These are precisely the cities where women work long hours or have high fertility rates. To address these issues, researchers typically take advantage of the fact that immigrants migrate to places where there are others of the same ethnic background. This strategy works well as long as historical settlement patterns of immigrant groups are not correlated with factors affecting the future labor supply and fertility decisions of high-skilled native women. This assumption may be questionable if the base year is very close to the years considered in the analysis.

Another potential problem is that these studies do not provide conclusive proof that immigrants affect native-born women’s decisions only through household services markets. Low-skilled immigrants may simply make high-skilled women more productive in the labor market, and this effect may explain the increases in labor supply and fertility rates. Inflows of low-skilled immigrants may also change cultural norms and housing prices, both of which may affect work and fertility decisions. Of course, if the concern is with immigration policy only, the precise mechanism through which immigrants affect the decisions of native-born women should not matter.

Even assuming that all of the estimates in this literature reflect causal relationships operating through household services markets, it is important to consider that responses to immigrant-induced changes in household services markets surely depend on cultural and institutional contexts. For example, in areas where high-quality childcare is inexpensive and readily available, immigrant inflows are not likely to be very influential. Similarly, if gender norms dictate that mothers care for children full-time, then again, immigration is unlikely to affect women’s family decisions. A study for Italy shows that the labor supply responses of high-skilled women are stronger in areas where publically provided childcare options are less available [4], while another study finds stronger impacts of immigration in countries with less supportive family policies [6]. Additional analyses that explicitly take into account cultural and institutional characteristics using data from several contexts may prove especially useful to policymakers evaluating different immigration policies.

Summary and policy advice

Many countries are grappling with setting optimal immigration policies. The focus of the debate has been on the wage and employment effects of immigration on workers who are close labor market substitutes for the typical immigrant. This issue and the fiscal implications of large immigrant inflows are certainly first-order concerns, but comprehensive immigration reform should consider the impacts of immigration on all segments of the population. To the extent that immigrants lower the wages of native-born workers, they also lower prices [12], in particular the prices of goods that are labor-intensive and non-tradable. Not only do childcare and other household services fit these characteristics, but policymakers should pay particular attention to these prices, which can influence women’s family decisions.

The gender earnings gap is an issue of considerable policy interest. The difficulty of combining work and family life is often cited as a major contributor to the glass ceiling limiting women’s career advancement. The earnings gap tends to increase with age and is especially high for women with children [13]. The evidence suggests that immigrant inflows increase the number of hours worked by high-skilled native-born women, particularly women who work very long hours. This implies that the cost, convenience, and perhaps quality of available childcare are impediments to mothers’ investing in their careers to the extent they would like.

Another policy concern in some countries, especially in southern Europe, are the below-replacement fertility rates. These low fertility rates are making pension plans that rely on population growth difficult or impossible to sustain. Because immigrants are typically of working age and tend to have larger families than natives, policymakers are using immigration, at least temporarily, as a way to alleviate below-replacement fertility rates. Immigration’s impact on the fertility rate of the native population should also be taken into account.

While all the studies discussed in this paper are about immigration, they speak more generally to the importance of childcare markets in women’s career and fertility decisions. Policymakers concerned about below-replacement fertility rates and gender earnings gaps may consider directly subsidizing childcare as a way to address these issues. The cost of these programs may be a concern, however. By allowing more low-skilled immigrants into a country, and perhaps specifically targeting visas to childcare workers, policymakers can lower childcare costs without depleting tax revenue. In fact, low-skilled immigration may bring fiscal benefits because immigrants’ household services are taxed (unlike the home production they replace) and their services free up married high-skilled women to work longer hours, often at high marginal tax rates. Thus, this type of immigration policy may even increase tax revenue.

Of course, for low-skilled immigration to have any impact on high-skilled women’s labor supply and fertility decisions, it must lower the wages of childcare and other household services workers during a time when inequality is already high in many countries. In addition, while the immigrants who work as household service providers may not themselves have harmful effects on state budgets, any spouses, children, and parents they bring with them may require social services, which can be expensive. The main policy take-away, however, is that immigration policy may influence not only the native workers who compete directly with immigrants for jobs, but many other groups in the population. All of the impacts should be considered when making policy decisions.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Delia Furtado