Elevator pitch

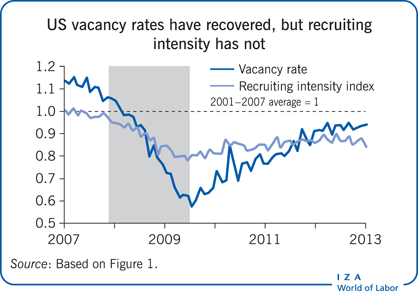

When hiring new workers, employers use a wide variety of different recruiting methods in addition to posting a vacancy announcement, such as adjusting education, experience or technical requirements, or offering higher wages. The intensity with which employers make use of these alternative methods can vary widely depending on a firm’s performance and with the business cycle. In fact, persistently low recruiting intensity partly helps to explain the sluggish pace of the growth of jobs in the US economy following the Great Recession of 2007–2009.

Key findings

Pros

An employer’s recruiting intensity is an important part of hiring and job creation.

Changes in recruiting intensity can account for some structural or “mismatch” unemployment.

Businesses that are fast-growing recruit more intensely.

Positions that offer higher wages tend to have greater recruiting effort and generate more interviewees per job offer.

Cons

Most theories of the labor market ignore recruiting intensity, so complicating policy analysis.

Recruiting intensity is difficult to measure and is not well understood by economists.

Little is known about which recruiting methods matter most, or which aspects of recruiting intensity might be most responsive to policy. Existing evidence is unable to identify supply- or demand-driven changes in recruiting intensity.

Author's main message

Recruiting intensity is important for explaining the hiring process at both the micro and macro levels. Persistently low recruiting intensity in the US since 2009 explains some of the divergence between the vacancy rate, which has recovered, and the hiring rate, which remains very low. Job creation policies that ignore how employers adjust recruiting efforts along multiple margins may fail to achieve their goals.

Motivation

When looking to hire workers, employers often do more than post a job vacancy. They can alter their hiring standards for a given position. They can do this explicitly, such as when they adjust specific education, experience, or technical requirements for a particular job—or implicitly, such as when they post a vacancy, but only in the hopes of attracting an outstanding candidate. Employers can also alter the wage offered. They can use above-market wages to attract more applicants, or increase the probability that job candidates accept an offer, in the hopes of filling a position more quickly. And they can vary the amount of resources they dedicate to recruiting, under the assumption that greater effort in the recruiting process will fill a position faster. These multiple methods can be collectively referred to as an employer’s “recruiting intensity.”

Employers tend to put the most effort into filling their vacancies when their business is growing rapidly and when the economy is expanding. Economists are just now beginning to understand the importance of these adjustments for labor market fluctuations.

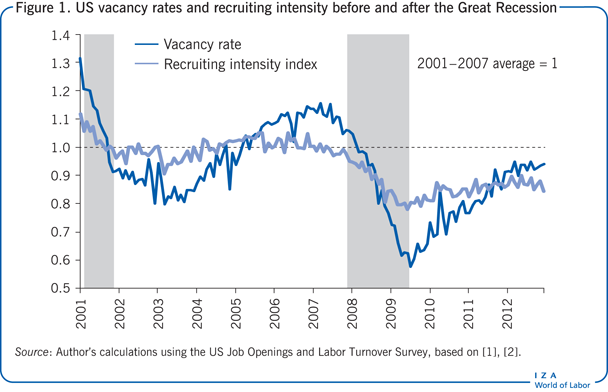

The experience of the US labor market following the Great Recession is a prime example of how changes in recruiting intensity affect the posting of job openings and the subsequent hiring for those positions. Since the end of the recession in mid-2009, the US vacancy rate has recovered to close to its pre-recession level, while the hiring rate remains very low (see Figure 1). Consequently, unemployment has remained stubbornly high. Persistently low recruiting intensity provides a partial explanation for this divergence.

Discussion of pros and cons

Recruiting effort and hiring outcomes

The fact that employers use multiple methods to attract and hire workers has been known for some time. Employers search more intensely when a position requires more formal training, or when the eventual hire is more educated or experienced [3]. Such positions are more difficult to fill, though, independent of the amount of recruiting effort. Recruitment strategies, and consequently how long a vacancy remains open, vary with the starting wage offered [4]. The duration of a vacancy’s posting reflects more of a screening period than a selection period, meaning that most job-seekers who are interviewed applied at the beginning of a vacancy’s posting [5]. The remaining time between the initial posting and the eventual hire is spent screening these applicants. This stands in contrast to the notion that a vacancy’s duration is a selection period whose length depends on how long it takes for a qualified applicant to walk through the door.

The relationship between the wage offered and the recruiting outcome shows that positions offering higher wages tend to have a greater recruiting effort by the employer and more interviewees per job offer [6], [7].

Recruiting intensity and business performance

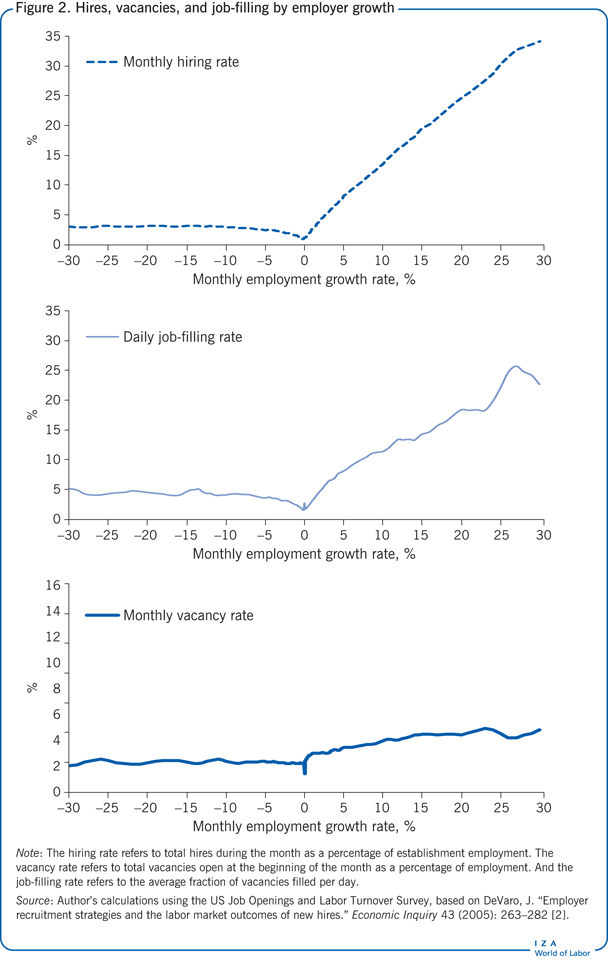

The knowledge on recruiting intensity has been furthered by documenting its importance for individual businesses and the economy as a whole, specifically by examining how recruiting intensity and hiring outcomes relate to a business’s performance and to the business cycle [1], [2]. The monthly hiring rate (total monthly hires, as a percentage of employment), the monthly vacancy rate (total vacancies open at the beginning of the month, as a percentage of employment), and the daily job-filling rate (percentage of vacancies filled daily) vary with establishment-level growth (see Figure 2).

First, there is a substantial amount of recruiting and hiring done at establishments that are contracting, though the pace is fairly stable in relation to the size of the contraction.

Second, there is a dip in the pace of recruiting and hiring for establishments with close to zero growth.

Third, hiring and vacancy rates rise with the size of an establishment’s expansion.

The hiring rate rises slightly more than one-for-one with the growth rate, while the vacancy rate rises much less than one-for-one. Thus, on average, businesses that expand their employment by 30% have a hiring rate of about 34% of employment, suggesting some turnover even as they rapidly expand, and a vacancy rate of just under 5%. The fact that hires and vacancies do not rise proportionally with an establishment’s growth rate implies that an establishment’s vacancy-filling rate must rise with the growth rate. As an establishment moves from zero growth to around 30% growth, the chances that it fills one of its vacancies on any given day rises from just under 3% to about 23% (see Figure 2).

The rise in the job-filling rate with establishment growth reflects the fact that fast-growing businesses recruit more intensely. These businesses, by definition, hire at a rapid pace. Consequently, they do much more than simply post many vacancies to attract these workers.

Keep in mind that some outside force must drive an employer’s decision to expand. For example, a sudden increase in the demand for a business’s product will cause it to ramp up production. In this case, it is not enough only to post vacancies. The business has a strong incentive to fill these vacancies quickly.

The methods at an employer’s disposal when doing so include all of the methods described above.

Employers could offer above-market wages to attract more applicants as well as make job candidates more likely to accept their offer.

They could also lower their hiring standards, perhaps opting for hires that are less experienced or less qualified than the people they would normally hire, with the thought that these individuals could be trained on the job or that the returns to growth outweigh the increased risk of worker turnover.

Employers could try to look at the widest range possible when attracting applicants, exerting significant effort through the use of networking, referrals, and the aggressive advertising of their job postings.

Finally, they could exert significant effort in the screening process, ensuring that enough quality applicants are interviewed to fill the available positions.

Recruiting intensity and the business cycle

A measure of recruiting intensity that captures these micro-level variations in employers’ recruiting behavior shows that changes in recruiting intensity can have considerable effects on the overall labor market [1], [2]. Specifically, aggregate measures of recruiting intensity vary with the business cycle, tending to fall during recessions and to rise during expansions. This is partly due to the fact that a slack labor market makes it easier for employers to hire in general, so less recruiting effort is required to achieve the same job-filling rate. At the same time, persistently low recruiting intensity can account for some of the shift in the US Beveridge curve following the Great Recession.

The Beveridge curve is the aggregate relationship between the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate. Since the end of the Great Recession, the vacancy rate has risen steadily while the unemployment rate has fallen slowly. This has led to an outward shift of the Beveridge curve, revealing that there are more unemployed workers for a given level of vacancies.

A plot of the relative movements in the US vacancy rate and the index of recruiting intensity over time shows that the vacancy rate fluctuates much more over the business cycle than recruiting intensity does. Between mid-2007 and mid-2009 (the official span of the Great Recession), the vacancy rate fell by about 50%, while recruiting intensity fell by about 22%. Since then, however, vacancies and recruiting intensity have diverged considerably. The vacancy rate has risen steadily. By the end of 2012, it was only 6% below its pre-recession average, despite its large decline. Recruiting intensity, however, was still nearly 16% below its pre-recession average (see Figure 1).

Recruiting intensity, matching efficiency, and unemployment

The relatively stagnant behavior of recruiting intensity following the Great Recession fits with the persistently high rates of unemployment in the US during this time. Between mid-2007 and mid-2009, the unemployment rate more than doubled, from 4.5% to a peak of 10.0%. At the end of 2012, the unemployment rate had only fallen to 7.8%. This slow decline, coupled with the rapid recovery in the vacancy rate, led to the shift in the US Beveridge curve. Multiple theories on the causes of this shift have arisen, each with considerable policy implications. Technically speaking, a shift in the Beveridge curve represents a change in the efficiency of matching workers to jobs. Since the vacancy rate rose faster than the unemployment rate fell, the shift reflects a decline in matching efficiency.

This decline can come about for a variety of reasons.

Some interpret it as a rise in structural unemployment. Under this interpretation, the skills of the unemployed do not match up with the skills required of the posted job vacancies. It may be that these workers’ skills deteriorated while they were unemployed, or that the industries posting vacancies are quite different from the industries where job-seekers were last employed, leading to a “mismatch” between job openings and job-seekers.

Another interpretation is that the technologies used to match workers to jobs have changed, though the rise in the use of online job search tools should increase rather than decrease matching efficiency.

Yet another interpretation is that the shift reflects a reduction in search effort by the unemployed, driven by a sharp rise in the amount of unemployment insurance benefits provided.

Hypotheses regarding structural change and unemployment insurance benefits have largely been refuted as being too small to account for the observed shift in the Beveridge curve. Using an index to measure the degree of mismatch between job-seekers and vacancies, it has been found that, while the index rises sharply during the Great Recession, it falls just as quickly following its end [8]. Using variations in the timing and length of benefit extensions across US states, the contribution of extended unemployment insurance benefits on the unemployment rate is found to be small [9].

The persistently low recruiting intensity seen in Figure 1 is at least a partial explanation of the shift in the Beveridge curve. The shift reflects increased “choosiness” on the part of employers, or alternatively an unwillingness to pay a wage that current job-seekers are willing to accept. One can expand upon standard economic theories of labor market search and matching to derive an estimate for the contribution of changes in recruiting intensity to shifts in the Beveridge curve. Doing so for the 2001−2011 period shows that changes in aggregate recruiting intensity account for about 20% of the shifts in the Beveridge curve [2].

Why recruiting intensity is not well understood

Changes in recruiting intensity have been inferred from the implications of a more generalized theory of labor market search and matching, with respect to the hiring and vacancy-filling process. This inference-based measure of recruiting intensity becomes a catch-all for a variety of different methods by which employers can affect hiring outcomes. From a policymaker’s perspective, it may be critical to know whether employers have cut back on actual recruiting effort, reduced the wages they are willing to offer, or increased their overall “choosiness” in the quality of job candidate that they prefer.

Even if one had detailed measures of the average qualifications employers sought for a potential hire, it would not be clear why these qualifications had changed. It may have been that the production technologies employers use improved, requiring a more skilled workforce. Alternatively, it may be that heightened economic uncertainty causes hesitancy on the part of employers in hiring all but the most spectacular candidates.

Knowing the root causes of a change in recruiting intensity is critical for policy. Policymakers may be able to offset changes in the relative wages offered by employers, or induce employers to offer a wage job-seekers are willing to accept, with various policy instruments, but policy options are likely to be more limited in affecting how choosy employers are in who they hire. Furthermore, policymakers will likely want to know if any change in recruiting intensity reflects something permanent, as with an increase in skill requirements due to the use of new technologies, or something transitory, as with a response to economic uncertainty.

For the most part, labor market theories assume that when a business wants to expand, it posts vacancies in proportion to the number of people it wants to hire. Even more sophisticated models that incorporate recruiting effort have the implication that recruiting intensity does not vary with the business cycle. Thus, there is little theory available to guide policymakers in how to think jointly about how businesses create jobs and the effort they put into filling those jobs.

Limitations and gaps

Recruiting intensity is an important part of fluctuations in the labor market, but several issues limit the policy recommendations one can give about recruiting intensity. First, the data available in most countries make a direct measurement of recruiting intensity nearly impossible. More generally, it is difficult to conclude why recruiting intensity may have risen or fallen, regardless of how well one can measure it. Finally, providing detailed policy implications regarding recruiting intensity is also hindered by the fact that recruiting intensity is generally ignored in the relevant economic theories of labor market search and matching.

First, the data available in most countries make a direct measurement of recruiting intensity nearly impossible.

More generally, it is difficult to conclude why recruiting intensity may have risen or fallen, regardless of how well one can measure it.

Finally, providing detailed policy implications regarding recruiting intensity is also hindered by the fact that recruiting intensity is generally ignored in the relevant economic theories of labor market search and matching.

Summary and policy advice

Recruiting intensity is an important part of the hiring process. Changes in recruiting intensity have implications at both the micro and macro levels. Employers’ recruiting intensity per vacancy varies systematically with the growth prospects of the business as well as the labor market conditions that the business faces.

Recruiting intensity includes a variety of methods at an employer’s disposal. Adjustments can involve changes in the employer’s hiring standards, in offering a wage substantially above or below the market wage for a particular position, or in the physical effort an employer puts into attracting applicants and screening candidates. Little is known about which recruiting methods matter most, or which aspects of recruiting intensity might be most amenable to policy.

Employers tend to put the most effort into filling their vacancies when their business is growing rapidly and when the economy is expanding. There is a substantial amount of recruiting and hiring done at establishments that are contracting, but the pace is fairly stable in relation to the size of the contraction.

In contrast, hiring and vacancy rates rise with the size of an establishment’s expansion. The hiring rate rises slightly more than one-for-one with the growth rate, while the vacancy rate rises much less than one-for-one. The rise in the job-filling rate with establishment growth reflects the fact that fast-growing businesses recruit more intensely. These businesses, by definition, hire at a rapid pace. So, they do much more than simply post many vacancies to attract these workers.

Aggregate measures of recruiting intensity vary with the business cycle, tending to fall during recessions and to rise during expansions. This is partly due to the fact that a slack labor market makes it easier for employers to hire in general, so less recruiting effort is required to achieve the same job-filling rate.

The vacancy rate rose faster than the unemployment rate fell after the recession, causing a shift in the Beveridge curve that reflects a decline in matching efficiency. Some interpret the decline as a rise in structural unemployment. Under this interpretation, the skills of the unemployed do not match up with the skills required of the posted job vacancies. Another interpretation is that the technologies used to match workers to jobs have changed, though the rise in the use of online job search tools should increase rather than decrease matching efficiency. Yet another interpretation is that the shift reflects a reduction in search efforts by the unemployed, driven by a sharp rise in the amount of unemployment insurance benefits provided.

Fluctuations in aggregate recruiting intensity provide an additional interpretation. Persistently low recruiting intensity reflects greater “choosiness” on the part of employers or their unwillingness to pay a wage that current job-seekers are willing to accept. Lower employer recruiting intensity makes it less likely that a job-seeker is hired for a given level of vacancies.

Job creation policies that ignore the fact that employers can adjust along multiple margins in the hiring process may fail to achieve their goals. For example, in the US, aggressive policies have focused on stimulating hiring during and after the Great Recession. Vacancies rebounded during this period, but recruiting intensity did not, and hiring remained low. Regardless of how employers go about recruiting, changes in the intensity of their efforts over time add an additional layer of complexity between the posting and filling of an open position.

Both policymakers and economists need a better understanding of what causes employers to vary their efforts in filling their job vacancies. Only then will policymakers be in a position to create effective targeted policies that boost hiring and reduce unemployment.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© R. Jason Faberman