Elevator pitch

In recent decades, the number of university students worldwide who have received some part of their education abroad has been rising rapidly. Despite the popularity of international student exchange programs, however, debate continues over what students gain from this experience. A major advantage claimed for study abroad programs is that they can enhance employability by providing graduates with the skills and experience employers look for. These programs also increase the probability that graduates will work abroad, and so may especially benefit students willing to pursue an international career. However, most of the evidence is qualitative and based on small samples.

Key findings

Pros

Study abroad programs may provide graduates with the skills and the experience employers are looking for.

By increasing the probability that graduates will work abroad, study abroad programs may especially benefit students who seek to pursue an international career.

Study abroad programs may improve the employment prospects of students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds.

Cons

University students may decide to spend some time abroad during their study not because they want to grow academically and professionally, but because they seek adventure and excitement.

While graduates who have studied abroad are found to be more employable relative to their non-internationally mobile peers, this difference may reflect the influence of unobserved individual characteristics, such as personality.

Most studies on the relationship between university study abroad and graduates’ employability are qualitative and anecdotal.

Author's main message

Employers, students, and administrators who manage international student mobility programs at higher education institutions perceive a connection between study abroad and graduates’ employability. This may call for greater promotion of study abroad programs in general, and particularly among students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds and in countries where participation has traditionally been low. However, given that individual unobserved characteristics driving the decision to study abroad are likely to be correlated with future labor market opportunities, it would be important to have more evidence that the perceived relationship is causal.

Motivation

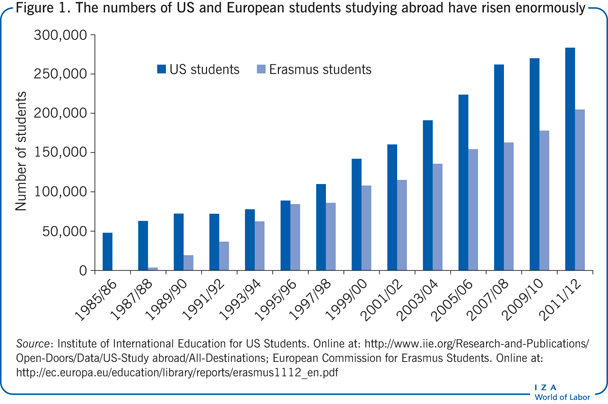

One well-known aspect of globalization in the higher education sector is the rapidly rising share of university students participating in study abroad programs. For instance, there is evidence that the number of students studying abroad has vastly increased in both Europe and the US (Figure 1). Available data indicate that between academic years 1987/88 and 2011/12 the number of students studying abroad through Erasmus (the EU’s flagship educational exchange program for higher education students) rose from 3,244 to 204,744. Erasmus, which facilitates mainly intra-European student mobility, is not the only channel through which European students may temporarily study in another country. However, harmonized data on participation in European study abroad programs other than Erasmus are unavailable. According to the Institute of International Education, in academic year 2011/12, 283,332 US students studied abroad for academic credit, representing about a 484% increase since academic year 1985/86.

Not only are study abroad programs already widespread, but their popularity is expected to increase. The European Commission recently launched the Erasmus for All program, which offers the possibility of studying abroad to many more students. More precisely, it will assist up to two million higher education students to study abroad over 2014–2020. In the US, the Institute of International Education actively collaborates with colleges and universities and with key public and private sponsors to boost the number and diversity of US students who study abroad.

Given this rising trend, it is important to understand the potential benefits stemming from study abroad. The claim is often made that study abroad programs help students better prepare for the labor market. However, linking the effects of participation in study abroad programs in a causal way to subsequent employment outcomes is challenging. Students who study abroad may differ from students who do not in unobserved characteristics that are likely to affect labor market outcomes. Economists need to address this problem through studies that provide causal estimates of the effect of studying abroad on graduates’ employment.

Discussion of pros and cons

Positive association between study abroad and employment prospects

Numerous studies have documented a positive association between participation in study abroad programs and graduates’ job prospects. These studies rely on data from surveys of former participants in study abroad programs, information collected from international mobility managers at higher education institutions, and evidence from employer surveys.

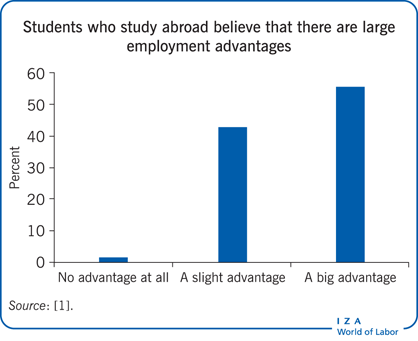

A few surveys have tracked the post-university outcomes of students who have spent part of their university studies abroad. Information from these surveys has been used to explore graduates’ perceptions about how their study abroad experience affected their subsequent employment career. For instance, one study examines data from a 2005 survey targeted to European students who studied abroad during academic year 2000/01 through the EU’s Erasmus program (the Professional Value of Erasmus survey, or VALERA survey). More than half (54%) of surveyed students believed that their study abroad helped them secure their first job [2]. This suggests that the majority of former participants in international study programs consider a period of studying abroad to be a positive addition to their résumé, one that helps them stand out in the labor market.

Other studies are based on data provided by university international mobility managers. A 2010 study, which relies on interviews with 11 mobility managers of different UK universities, concludes that participation in study abroad programs strongly enhances employability. One university international mobility manager was able to report results from a survey of graduates who had spent one year abroad during their university studies: 87% of respondents stated that their experience abroad contributed to making their job interview more successful. Furthermore, 75% of respondents indicated that their current employer would be more likely to offer a job to someone who had studied abroad. Another interviewee was told by a chief executive of Lloyds TSB that the company looks for global graduates when it recruits employees [3].

Finally, some studies have examined the extent to which employers are attracted to applicants who have studied abroad. Using data from a survey of 230 employers in the UK, a 2007 study finds that 29% of the employers felt that graduates with overseas study experience were more employable [4]. There is also evidence from Australia supporting the proposition that employers highly value graduates with overseas study experience. A 2006 survey of senior recruitment and human resource managers from more than 100 Australia-based multinational, national, and state organizations (commissioned by the Queensland Government and the International Education Association of Australia) found that 60% of the respondents believed that experience with overseas study provides a “unique, competitive” advantage to a graduate’s résumé.

Relevant employment skills acquired through study abroad programs

Studying abroad may give students the opportunity to acquire a wide range of skills that enable them to compete successfully in the labor market. Many internationally mobile students are likely to become fluent in a second language. There is some evidence from the US that speaking a foreign language is rewarded in the labor market. Using a representative sample of US college graduates, one study finds a 2–3% earnings premium for employees who are bilingual. This result is robust to a variety of empirical strategies, including ordinary least squares regressions with controls for cognitive ability and nonparametric methods based on propensity score matching and panel data methods [5]. There are of course different premiums for different languages. For instance, in the US, speaking Spanish as a second language does not pay off as much as speaking German does. Not only is fluency in a second language a crucial asset in an increasingly globalized economy, but plurilingualism is also known to bring cognitive advantages.

While foreign language skills are often viewed as the most important benefit emerging from study abroad, there are many other advantages. Intercultural competence and willingness to be internationally mobile are likely to be highly valued in a global economy. Graduates who have spent some time overseas during their university studies are more likely to work effectively in a multicultural environment and may be more open to working in other parts of the world during their career. Former participants in student exchange schemes are likely to be more flexible and open to change, enabling them to adapt to new situations, embrace different perspectives, and deal with ambiguity. Additionally, study abroad programs may enhance students’ confidence and self-awareness. While studying and living abroad, students have to deal with new and unexpected situations, which can help them to become more confident, mature, and self-reliant. Finally, an overseas educational experience gives students the possibility of building a network of international contacts and thus of expanding their options of finding a job after graduation.

Employment-related disadvantages of studying abroad

While there are several reasons why study abroad is positively associated with graduates’ job prospects, there are also some possible negative employment-related consequences of this experience. Some of the knowledge and skills that students acquire while studying abroad may not be transferable to the labor market in their home country. For instance, internationally mobile students may become familiar with accounting and legal procedures that are used in the study abroad country but not in their home country.

Another possible disadvantage associated with studying overseas is that not all graduates are able to translate their study abroad experience into something employers value. In job interviews, employers sometimes get the impression that students pursue study abroad for the fun and excitement it offers rather than to pursue specific academic goals.

There is also evidence that studying abroad may negatively affect the transition from higher education to employment. Using data from 16 European countries, a recent study concludes that internationally mobile students take slightly longer to find a job than do their peers who do not study abroad [6]. However, this effect holds only for students who have spent at least six months abroad, and it is significant in a few countries and in a few subjects of study. This result may be partly due to the greater difficulty of developing an employment network for students who are studying abroad. Participants in study abroad programs may find it harder to create and maintain social connections in their home country. Given that in many labor markets jobs are often obtained through informal channels, internationally mobile students may need to spend more time searching for a job. Another reason for the longer transition to employment after graduation for internationally mobile students is that they are more likely to continue their studies than are their peers who did not study abroad.

Study abroad and an international career

Studying abroad may be especially beneficial for students who are willing to pursue an international career. Many students decide to study abroad because they view this experience as an opportunity to develop an internationally oriented career. However, not all participants in international student mobility programs are determined to pursue a globally oriented career before they go overseas. An education abroad experience may actually induce some students to do so.

Several studies report that former participants in study abroad programs are more likely to be employed in multinational companies and work overseas than their non-internationally mobile peers. A survey conducted by the Institute for the International Education of Students found that nearly half (48%) of US students who studied abroad during at least part of their university years reported working in a globally oriented position at some point after graduation. Similar evidence for European students emerges from the VALERA survey. Graduates who studied abroad through the Erasmus program are more likely than other students to work in internationally oriented organizations and carry out work tasks with an international component [7]. More precisely, compared with workers who had no international study experience, former Erasmus participants are more likely to be sent abroad for work assignments, more likely to travel to other countries on business, more likely to use foreign languages in professional situations, more likely to use information about other countries in their work, and more likely to work with colleagues or clients from other countries.

A few studies provide causal evidence of the positive influence of participation in international student exchange programs on graduates’ likelihood of working in a foreign country. Two of these studies, which rely on a similar identification strategy, look at German and Italian graduates [8], [9]. The German study focuses on the effect of the Erasmus program, while the Italian study analyzes the impact of all student exchange schemes. The two studies reach similar conclusions: studying abroad increases the likelihood of later working abroad—by 15 percentage points for German students and by 18–24 percentage points for Italian students—compared with students who have not studied abroad. Another study using data on Dutch university students uses a regression discontinuity design (a quasi-experimental study design used to determine the causal effects of social programs or interventions when randomization is not feasible; it compares observations that lie close to both sides of a predetermined threshold to estimate the local average treatment effect) to account for the endogeneity of the decision to study abroad [10]. The empirical findings suggest that studying abroad raises the probability of working in a foreign country by approximately 50 percentage points. There are two possible reasons for the wide differences in the magnitude of the effect related to studying abroad. First, while the German [8] and Italian [9] studies use a nationally representative survey of university graduates, the Dutch study [10] employs a small sample of particularly talented students. Second, the German and Dutch studies examine the impact of undergraduate studies abroad, while the Dutch study investigates the effect of postgraduate studies abroad.

In line with expectations, there is also evidence that the probability of working abroad following graduation is positively related to the duration of the international study experience. The more time spent studying at a foreign university, the higher is the likelihood of later having a job in a foreign country. One study finds that for European students who spent 12 months abroad, the probability of working in a foreign country within five years of graduation is more than the double that of their peers who studied abroad for three months [6].

Finally, there is descriptive evidence from Germany that internationally mobile graduates tend to return to the country where they studied abroad [8]. The reason for this choice is that while studying abroad students are likely to acquire skills and knowledge (such as language skills and personal contacts) that are generally more relevant in that labor market than elsewhere.

Accounting for unobserved characteristics of students who study abroad may be relevant

A major challenge of research investigating the employment effect of studying abroad is that it should account for the possibility that unobserved individual characteristics driving the decision to participate in international student exchange schemes might be correlated with subsequent employment outcomes. There are at least two sets of arguments suggesting that students who study abroad are weaker on unobserved dimensions that may be related to future labor market opportunities. First, many students decide to study abroad not because they want to gain competence in academic and professional domains but because they are looking for adventure and excitement. Second, it is also possible that some students view the experience as an opportunity to put less effort into their education since examinations tend to be easier in study abroad programs. International exchange students may receive special treatment, which can improve their odds of passing exams and getting higher grades. Additionally, students may intentionally choose study abroad programs with lower examination standards than their home university. For example, in one Italian university several student exchange links with international higher education institutions were suspended following an investigation that found that many students were choosing these destinations because of their lower examination standards.

On the other hand, the decision to spend some time abroad during university studies can be associated with unobserved student traits that positively affect labor market outcomes after graduation. In line with this consideration, one study, using data from a large sample of first-year US college students, finds that the intention to study abroad can be positively predicted by factors such as openness to diversity in ideas and people, interest in writing and reading, diverse interactions while in college, and participation in extracurricular activities [11].

Limitations and gaps

Evidence on the positive association between participation in international student mobility schemes and graduates’ employment prospects comes mainly from anecdotal and qualitative studies. With only a few exceptions [8], [9], [10], the studies discussed here do not account for the possibility that the decision to study abroad may reflect unobserved (or difficult or impossible to measure) individual characteristics that are likely to be correlated with future employment prospects. This means that these studies are unable to separate the effect on future employment outcomes triggered by participation in study abroad programs from the effect of unobserved individual characteristics driving the decision to study overseas. Since, as discussed above, these omitted factors could have either a positive or a negative impact on employment (selection into study abroad programs can be positive or negative), the conclusions of the studies mentioned above may overestimate or underestimate, respectively, the true employment effect of studying abroad. Given the substantial amount of public resources devoted to study abroad programs, it is important to identify the true impact of these programs on job prospects by conducting more studies that can also account for the possibility that the decision to study abroad may reflect unobserved individual characteristics.

To the best of this author’s knowledge, only one study has attempted to examine the causal effect of studying abroad on graduates’ subsequent employment probability [12]. The identification strategy uses students’ exposure to international exchange programs as a source of exogenous variation in the probability of studying abroad. This study concludes that Italian graduates who have studied abroad as part of their degree are approximately 23 percentage points more likely to be in employment three years after graduation relative to their non-internationally mobile peers. Given that Italian students who study abroad may have different preferences and personality traits than similar students in other parts of the world, more comparative studies are needed on the causal employment effect of studying abroad. Not only is such additional causal evidence necessary before any generalizations can be made, but it could also help international, regional, national, and local institutions make more informed decisions on whether to support initiatives to encourage cross-border student mobility. Furthermore, this evidence may help parents and students, for whom studying abroad often represents a substantial investment.

Summary and policy advice

There are many potential advantages associated with participation in study abroad programs. One is that an international education experience may enable students to acquire a vast array of skills that can help them find a job once they enter the labor market. It may be especially helpful to students who are interested in pursuing globally oriented careers. The employment advantage of studying abroad is recognized by participating students, employers, and mobility managers of higher education institutions.

The large amount of qualitative and anecdotal evidence that studying abroad pays off in the labor market provides some support for initiatives aimed at increasing the number of participants in such programs. For instance, the EU’s Erasmus for All program recognizes the importance of helping young people acquire training and skills that can increase their personal development and improve their job prospects. However, such initiatives should be accompanied by provisions to raise students’ awareness of the benefits of an overseas experience.

Such awareness-raising measures should be targeted especially to students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds. On the one hand, these students are less likely to receive relevant information about the advantages of studying abroad from their parents and friends. On the other hand, an international education experience may significantly improve their labor market prospects. It may provide them with an opportunity to develop many marketable skills (such as intercultural competence, global awareness, and foreign language skills) that their background would not otherwise have exposed them to. Of course, appropriate financial support should be given to students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds to help them afford studying abroad. However, more than financial barriers prevent this group of students from studying overseas. Cultural factors, such as negative family attitudes toward the value of international experience, may play an important role in discouraging the participation of students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds in study abroad programs.

Another advantage of interventions that encourage students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds to study abroad is that such interventions may slow the growth of inequality. A very large proportion of Erasmus participants have parents with a higher education, and this share has not changed much over time [13]. Given that students from relatively advantaged backgrounds are more likely to take up study abroad opportunities, this experience may further enhance their labor market position compared with students from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds. These interventions could also reduce inequality if returns from an international experience are higher for students from more disadvantaged backgrounds than for students from less disadvantaged backgrounds.

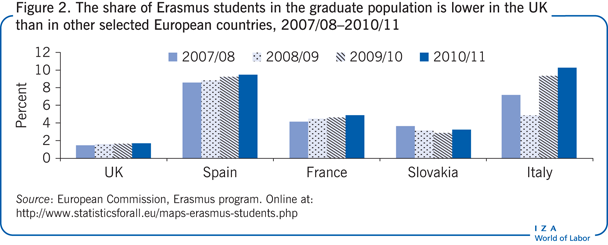

At the same time, it is important to increase awareness of the benefits of studying abroad among students in countries where participation in international student exchange programs is comparatively low. For example, the share of Erasmus students as a percentage of the graduate population is much lower in the UK than in other European countries (Figure 2). In addition, internationally mobile students in the UK are disproportionately young, female, white, and from more advantaged socio-economic backgrounds [3]. Therefore, study abroad programs in the UK should be promoted especially among students who are mature, male, from ethnic minorities, and from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

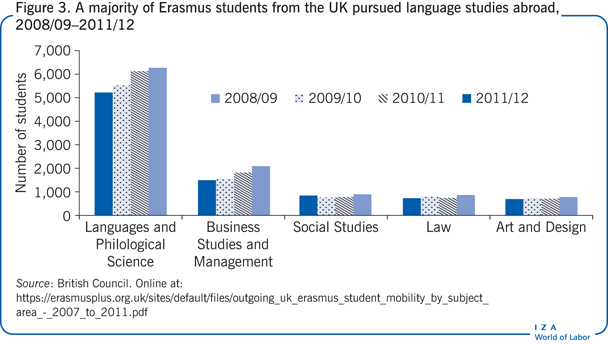

It is also important to let students know that the employment benefits related to studying abroad accrue not only to students pursuing a specialist language degree, but also to students pursuing other courses of study. For example, in the UK a large proportion of students studying abroad are language specialists. In the academic year 2011/12, nearly 58% of outgoing UK students in the Erasmus program studied languages and philological science (Figure 3). This finding suggests that many UK non-language students are deterred from studying abroad by a lack of foreign language skills. Several measures could be taken to address this obstacle. First, students can be informed that they could benefit from an international mobility experience even if they are not fluent in the relevant language when they start out. Second, higher education institutions could allocate more resources to language centers or extracurricular courses provided by language departments. Third, foreign languages could be made compulsory at both primary and secondary school.

Finally, many institutions, students, and parents are making decisions about study abroad programs based on their beliefs that the programs improve the employment prospects of participants. While correlational and anecdotal studies all point in that direction, more causal studies are also needed to confirm these impacts and their size.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Giorgio Di Pietro