Elevator pitch

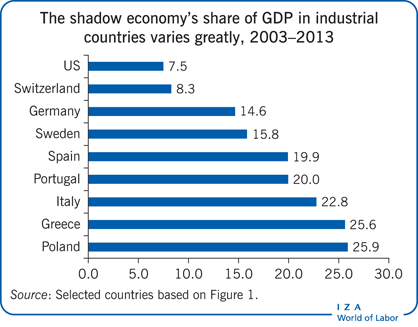

The shadow (underground) economy plays a major role in many countries. People evade taxes and regulations by working in the shadow economy or by employing people illegally. On the one hand, this unregulated economic activity can result in reduced tax revenue and public goods and services, lower tax morale and less tax compliance, higher control costs, and lower economic growth rates. But on the other hand, the shadow economy can be a powerful force for advancing institutional change and can boost the overall production of goods and services in the economy. The shadow economy has implications that extend beyond the economy to the political order.

Key findings

Pros

High taxes and social security contributions and heavy regulation are the main drivers of the shadow economy.

Resources not being used in the official economy can be used in the shadow economy to increase overall supply of goods and services.

Opinions on how to deal with the labor force in the shadow economy differ widely.

Governments try to encourage firms to move out of the shadow economy by improving public institutions.

Fostering stronger popular participation in government decision-making, expanding elements of direct democracy, and eliminating corruption can also reduce the shadow economy.

Cons

The shadow economy is hard to measure, and different methods yield different results.

Some measurement difficulties occur because the shadow economy is not clearly defined.

By worsening fiscal deficits and reducing infrastructure investment, the shadow economy reduces welfare and economic growth.

The shadow economy can undermine state institutions, leading to more crime and less support for institutions, ultimately threatening economic and political development.

Trying to reduce the shadow economy through punitive fines and tighter controls is costly and not very effective.