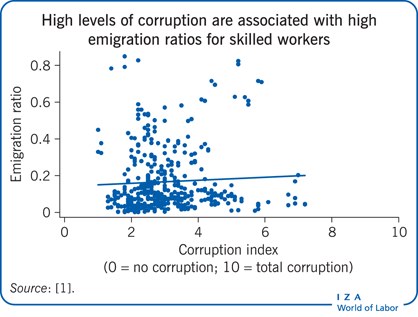

Elevator pitch

Knowing whether corruption leads to higher emigration rates—and among which groups—is important because most labor emigration is from developing to developed countries. If corruption leads highly-skilled and highly-educated workers to leave developing countries, it can result in a shortage of skilled labor and slower economic growth. In turn, this leads to higher unemployment, lowering the returns to human capital and encouraging further emigration. Corruption also shifts public spending from health and education to sectors with less transparency in spending, disadvantaging lower-skilled workers and encouraging them to emigrate.

Key findings

Pros

Since corruption lowers the returns to human capital, reducing corruption prevents brain drain by retaining an educated labor force, which can boost economic growth and welfare.

Control of corruption allows good governance to emerge, boosting the welfare of people across all education levels and encouraging them to stay in the country.

There is evidence that the exact relationship between corruption and emigration might vary for workers with different levels of skills and education.

Measures to reduce corruption should be accompanied by measures to reduce inequality.

Cons

When corruption increases, there are larger outflows and smaller inflows of highly-educated workers, resulting in a net brain drain, which reduces welfare in the home country and slows economic growth.

Emigration flows of people with low and medium skills and education rise at initial levels of corruption and then decline as corruption reaches a certain threshold.

Corruption reduces the stock of human capital and the returns to education by slowing growth, generating unemployment and underemployment, increasing inequality, and reducing welfare.