Elevator pitch

An extensive program of economic liberalization reforms, even when it generates positive outcomes, does not automatically generate support for further reforms. Societies respond with strong support only after experiencing the effects of reversing these reforms (i.e. corruption, inequality of opportunity). This point is illustrated through the example of the post-communist transformation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia—arguably a context where the end point of reforms was never clearly defined, and even successful reforms are now associated with a degree of reform suspicion.

Key findings

Pros

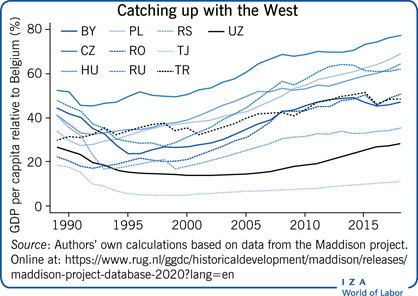

The majority of transition countries have grown economically, and they have all become functioning markets.

Transition countries have become institutionally more similar to countries at their level of GDP per capita, and many, but not all, have become more democratic.

Inequality, as measured by Gini, is today fairly low by world standards in transition economies.

Support for economic liberalization reforms only increased in societies that experienced the effects of reversing these reforms (corruption, inequality of opportunity).

Cons

Transition paths in the region overall have been very diverse and outcomes unequal.

Reforms have often been associated with perceived unfairness, and the perception of corruption has increased in some countries.

Corruption contributes to inequality of opportunity, which is higher in transition countries than elsewhere.

Even when reform outcomes have been positive, support for reforms has fallen.