Elevator pitch

An extensive program of economic liberalization reforms, even when it generates positive outcomes, does not automatically generate support for further reforms. Societies respond with strong support only after experiencing the effects of reversing these reforms (i.e. corruption, inequality of opportunity). This point is illustrated through the example of the post-communist transformation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia—arguably a context where the end point of reforms was never clearly defined, and even successful reforms are now associated with a degree of reform suspicion.

Key findings

Pros

The majority of transition countries have grown economically, and they have all become functioning markets.

Transition countries have become institutionally more similar to countries at their level of GDP per capita, and many, but not all, have become more democratic.

Inequality, as measured by Gini, is today fairly low by world standards in transition economies.

Support for economic liberalization reforms only increased in societies that experienced the effects of reversing these reforms (corruption, inequality of opportunity).

Cons

Transition paths in the region overall have been very diverse and outcomes unequal.

Reforms have often been associated with perceived unfairness, and the perception of corruption has increased in some countries.

Corruption contributes to inequality of opportunity, which is higher in transition countries than elsewhere.

Even when reform outcomes have been positive, support for reforms has fallen.

Author's main message

It is entirely justifiable to ask whether the post-communist transition, which began in 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia, can be considered to be over. Perhaps equally important is to understand the impact and perception of reforms implemented since then. Interestingly, reform success seems to weaken societal support for future reform. In contrast, experiencing the consequences of reform reversals (corruption, inequality of opportunity) appears to strengthen support for reforms. A key takeaway is that new waves of economic reforms should aim not only at high GDP growth but also at eradicating corruption and cronyism, strengthening the rule of law, and strengthening social mobility.

Motivation

The year 1989 started with round table talks between the, at that time, underground Polish trade union Solidarity's leaders and the Polish Communist Party Politburo in February, and finished with the destruction of the Berlin Wall in November. That year symbolically marks the beginning of “transition,” which has both political and economic aspects. First, it relates to the process of intense political transformation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia away from Communist Party dictatorships. Second, it relates to a process of change in economic institutions, away from the centralized command and control system known as “central planning.”

But what was the end point? When would the transition be over? The lack of clarity or consensus over what the end of transition would look like continues to be an issue for academics, policymakers, and societies today. It is thus a worthwhile endeavor to critically discuss different possible “end points,” how they compare to where societies are today, and why it matters. Is the transition over?

Discussion of pros and cons

Most transition countries have not caught up to Western European living standards

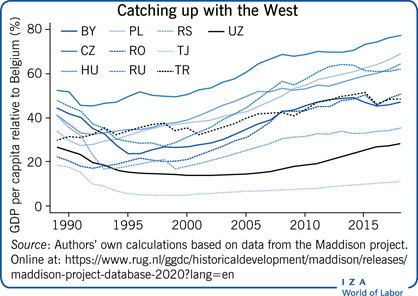

A first possible end point for transition is to align the process with a full catch-up to Western European living standards. While this seems like an ambitious objective, researchers have described this as a credible “popular view” in the region [1]. The Illustration presents GDP growth paths from the early 1990s to date for the nine most populous transition countries, plus Turkey, relative to Belgium, taken to represent a reference growth profile within the EU.

Indeed, performance patterns have been complex, but three key factors can be highlighted [2]. First, countries which made good progress in their institutional reforms grew faster (typically all the new EU countries such as Czechia, Hungary, and Poland, but especially the faster reformers; compare with the weaker growth in Romania). Second, countries which did not experience war or ethnic conflict (unlike e.g. Serbia and Tajikistan) performed better. Third, among countries where reforms have been partial or delayed (e.g. Belarus, Russia, Romania, Serbia, and Uzbekistan), those with natural resources have fared better in terms of GDP growth (e.g. Russia), even if their institutional reforms have been weaker. With this in mind, performance in every transition country has fallen short of a catch-up with Western Europe, even if the rate of convergence has progressed.

Accordingly, differences in institutional outcomes require further investigation, as they appear highly relevant to the growth paths observed since the beginning of transition.

Transition countries’ regulatory environments are similar to market economies at comparable income levels

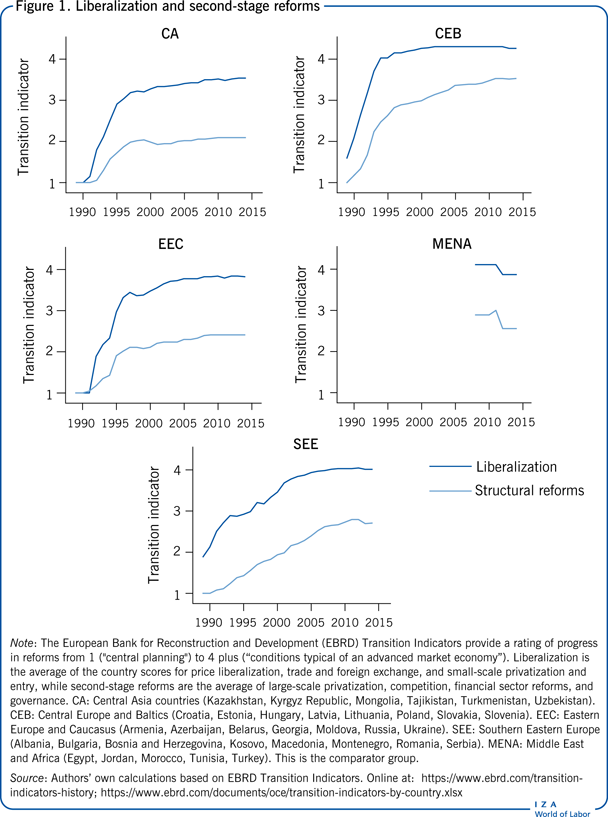

A second approach is to consider the end point of transition as becoming “a typical market economy,” focusing on the development of market-supporting regulatory environments. This is in line with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Transition Indicators (TI), which provide a rating of progress in reforms from 1 (“central planning”) to 4 plus (“conditions typical of an advanced market economy”). The TIs further split internally between two components: (i) liberalization (internal price liberalization, external trade liberalization, plus small-scale privatization and conditions for business entry) and (ii) structural reforms (privatization of large enterprises, governance and finance, and competition policy).

Notably, the post-communist transformation may have been over for a while in most of the former Soviet bloc according to the liberalization component. Indeed, already in the late 1990s most transition economies, except for a few laggards (Belarus, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), had reached a score of 4 for liberalization, thus demonstrating that the bare-bones structures of markets were in place.

A decade later, most of the Central and Eastern European countries plus the Baltic republics were also scoring 4 (or close to 4) on the more challenging aspects of reforms as captured under the term “structural reforms,” demonstrating impressive progress in institutional development. Yet things looked different in most of the former Soviet Union republics.

Figure 1 captures the reform timeline until the year 2014, the last year for which the comparable scores are available (the Czech Republic no longer wants to be considered in transition by the EBRD metric and is thus not included). Conveniently, there is also a benchmark from outside the former Soviet bloc; five countries from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region were added to the EBRD program later on. Regional comparison suggests that, by 2014, the post-communist countries did not look different from the MENA group on the core liberalization measures. However, progress was more uneven on the structural reforms indicators. Central European countries and Baltic republics (CEB) exceeded MENA levels after only a few years of transition, and South Eastern Europe (SEE) achieved them by around 2010. Meanwhile, former Soviet republics in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus (EEC) and Central Asia (CA) were still lagging behind. Thus, structural reforms have been considerably slower, and exhibited striking regional differences in terms of progress; these cross-regional differences appeared early on, and persisted over time.

The emerging divide is thus between countries that either became EU members or aspire to (typically with association agreements), and those that did not. However, EU integration is not an external factor and the causality is complex: EU integration could well be a function of reforms, as much as reforms follow from (or preempt, but are motivated by) EU integration. For example, the three Baltic republics (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) were initially not considered frontrunners in the EU accession race, but their progress with economic and political reforms, with the explicit objective of joining the EU, moved their position up.

Economic indicators of transition countries are now mostly “typical” of countries at similar income levels

A third approach to conceptualizing the end point of transition is to look not at the regulatory dimension but at structural economic features: querying whether transition countries are now showing economic characteristics that are typical of a country at their level of development, that is, with similar income or GDP per capita. This is the approach chosen by a number of researchers [3], [4], who view the end of transition as a point at which post-communist countries no longer bear the economic scars of their communist experience. Ten years into the process, transition countries still differ slightly from countries that were at the same level of development but did not share their communist past. The differences include that transition countries have “a larger share of their work force […] in industry, use more energy, have a more extensive infrastructure and invest more in schooling” [5]; p. 1. But, by 2014, transition economies were “normal” in a structural economic sense by most indicators [3].

Re-examining the question of normality over a large set of indicators, a recent study shows that transition countries are now comparable with other market economies at similar levels of economic development [4]. Reforms have allowed for most of the economic distortions of the past to be remediated, and post-communist countries are now in many ways comparable to their neighbors without a communist past (i.e. countries with similar geographic conditions, trade potentials, and geo-political constraints). To some extent, these are signs that transition countries have returned to their long-term development paths. The author of this recent study does note two points of distinction: the financial sector (less developed), and the share of the government in ownership of enterprises (larger) [4]. Furthermore, two important (and related) topics—the heritage of high energy use [2] and environmental pollution—are not addressed.

While transition countries are generally considered “normal” in terms of structural economic considerations, the dimension of financial development is an exception; it is lower than what could be expected given their GDP levels [4]. In an earlier investigation, important distortions were highlighted in the financial structure of transition economies compared with OECD countries [6]. The study also shows that medium-term growth was negatively affected by these distortions, thus empirically demonstrating the negative impact of underdeveloped or unbalanced financial institutions and markets [6]. This underdevelopment is perhaps unsurprising considering that formal private finance did not exist in these countries 30 years prior. Underdeveloped financial sectors may also limit social inclusivity and mobility, therefore indirectly damaging the perceptions of economic fairness.

Another difference is related to the size of the state sector [4]. By international standards, transition economies generally continue to have large state-owned firms. This is what still links a number of Central Eastern European countries to China and other South East Asian states with histories of communism. It also links them to other countries with totalitarian heritage of a different brand, for example Italy [7].

The communism experience was variable, so are its legacies

It has been posited that applying a uniform “post-communist” label to all transition countries may be misleading. The experience of communism varied, which may have a lasting legacy. For example, while being unemployed or holding even small private commercial property was illegal in some communist countries, this was not the case in some others (e.g. Hungary, Poland, or Yugoslavia). In particular, the Stalinist period was characterized by very specific patterns of industrialization, creating industries that later proved unviable, especially once relative energy prices started to increase in the late 20th century [2]. This period's impact on both long-term growth and willingness to accept reforms may thus be crucial. For example, social trust remains lower in areas close to former Gulag camps [8]. To detect such effects, within-country variation needs to be examined.

Looking for a single quantifiable indicator, researchers have focused on the amount of time that a country spent under communism, which strongly correlates with the amount of time spent under some of the most damaging periods or forms of communism, especially under the Stalinist system. In that vein, it was found that 58% of the variation in the implementation of regulatory reforms can be explained by the amount of time a country spent under a communist system [9]. Thus, the differing pre-transition conditions have strong differentiating effects on both reforms and structural economic features.

Not only the regulatory reform but the wider issues of inequality and institutional quality matter

A final approach regarding the end of transition is to consider it as the point at which higher-order institutional quality is on par with advanced economies. For example, corruption can be seen as a central institutional outcome, key to the overall assessment of institutional quality, and closely and inversely related to the rule of law [10]. Society's experience with corruption matters. First, it affects productive activities, leading to lower growth ambitions, and less economic dynamism [11]. Second, it affects life satisfaction, with one byproduct being higher propensity to emigrate [11].

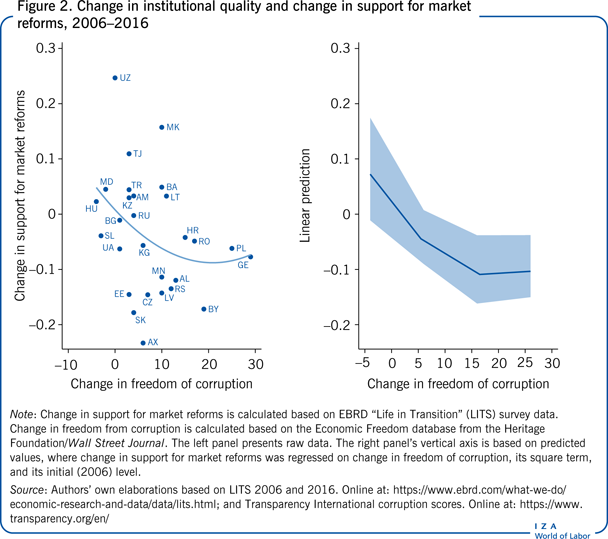

Researchers indicate that the perception of corruption in the region remained high following transition, yet argue that experience with bribe-paying appeared to be no higher than in some other comparable countries (e.g. comparing Russia to Brazil) [3]. However, recent observations show that more progress has been made with regulatory reforms than with overall institutional quality and corruption [11]. Moreover, there have been tangible reversals associated with increased corruption in a number of countries [11]. Prime examples of institutional reversal include Hungary, Slovenia, and Moldova (see Figure 2). Moreover, while institutional progress in transition countries has slowed in recent years, it has continued elsewhere. The net result is that the gap between transition countries and both comparator countries and the G7 group (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US) is widening [11].

Another important channel of the societal impact of corruption is through inequality of opportunity. Inequality of opportunity is that part of inequality which is explained by an individual's circumstances at birth: place of birth, sex, ethnicity, and parental background [12]. Market mechanisms alone may award acquired human capital characteristics with better jobs. However, if instead the major factor explaining earnings and quality of jobs is an individual's parents’ level of education (followed by gender and place of birth), as is the case in transition economies, that indicates a systemic failure [12]. Low institutional quality, as captured by corruption indicators, is a prime factor here.

This implies a complex role of rising inequality on support for economic liberalization. On the one hand, if inequality rises because efforts are better rewarded, as should be the case in a functioning market economy, this socially acceptable form of inequality should be associated with increased support for reforms [12]. But on the other hand, rising inequality reflecting greater inequality of opportunity is more likely to translate into decreasing support for reforms, especially if reforms are thought to be the cause [12]. Importantly, the transition experience has illustrated that partial reforms are associated with greater inequality of opportunity (as well as greater levels of corruption and lower institutional quality) compared to more extensive reforms.

This gives rise to a complex situation as the general public in transition countries may not necessarily distinguish between complete, consistent reforms and partial reforms scenarios, associating both with movement toward “the market.” It is the incomplete reforms, for example partial trade liberalization that left scope for arbitrary government decisions and therefore cronyism, which have led to corruption, emerging oligarchies, and strong perceptions of inequality [1]. Furthermore, when economic liberalization reforms have been implemented, and then reversed, worsening of outcomes is more easily attributed to the reversal and thus can lead to increasing support for reforms.

Relatedly, there is evidence that rising perceived inequality can damage trust and lower life satisfaction, but will also impact people's preferences toward redistribution or government interventions [12]. In the transition region, perceived inequality is particularly high, with social perceptions largely overestimating the extent of real inequality. This likely links back to the distinction between economically explained inequality and inequality of opportunity. It is inequality of opportunity that may have the strongest impact on the perceptions of inequality. In many transition countries, there has been rising inequality of opportunity, a perceived lack of fairness, and a reduction in social mobility since the 1990s. When such inequality is perceived as resulting from cronyism, favoritism, and corruption, which all represent aspects of low institutional quality [10], social tolerance and acceptance of inequality is likely to be lower. In turn, low tolerance for inequality leads to an increase in its perceived level.

Support for market reforms

The evolution of public support for market reforms (from EBRD “Life in Transition” surveys) is shown in Figure 2. As seen, the share of the population supporting market reforms in Eastern Europe and Central Asia is varied but not out of line with what is observed in old EU countries and even Turkey. However, support appears to have fallen between 2006 and 2016 (the two points in time at which the EBRD conducted its Life in Transition surveys) in a majority of cases throughout the post-communist region.

Yet support for reforms increased in countries where corruption increased. The effect is driven primarily by Central Asian republics, but also Hungary and Moldova. In contrast, improvement in institutional quality was not associated with increased support for market reforms. Thus, asymmetry is observed. Societies respond more to negative changes than to positive ones. This is in line with the lessons from cognitive psychology, and in particular with “prospect theory,” which posits that losses loom larger than gains. As documented in [13], individuals respond much more strongly to institutional deterioration than they do to institutional improvement. This literature implies that instead of the vicious circles where poor reforms lead to poor outcomes and low support for further reforms, support for reforms actually increases if worsening outcomes can be understood as being caused by reversals, leading over time to corrections in policies and to institutional improvement. Of course, the scenarios are less optimistic if parallel with deteriorating institutional quality, the corresponding regimes build their capacity to resist reforms and change.

Limitations and gaps

There are some major limitations both to the discussion in this article and in some aspects of the transition literature at large. First, are institutional measures provided by inter-governmental organizations like EBRD and the World Bank unbiased? To what extent are they subject to political pressure from the countries these institutions are supposed to evaluate? Do they measure what they intend to measure?

Second, these are highly complex issues. There is a circle of mutual dependence that is difficult to disentangle. Both regulatory reforms and more fundamental change of higher-order institutions affect societal attitudes and satisfaction, but how exactly, and in which direction? In turn, how and under which conditions do satisfaction and attitudes translate into political decisions, thereby modifying the course of reforms? And finally, do reform reversals and reform persistence generate equally strong responses?

Third, 30 years after the transition started, different issues may matter more for the youngest generation. Climate change and protection of the natural environment are an obvious suggestion here. Are researchers therefore still asking questions that are seen as the most critical to the regions’ populace?

All this indicates that there is still plenty of work to do in the fascinating line of research on transition, and more broadly on institutional change.

Summary and policy advice

To conclude, the devil is in the details. Transition countries have experienced significant progress with respect to regulatory environments, and the structural features of their economies have become similar to economies at their level of development elsewhere. However, it is the lived experience of citizens that critically matters, with unfairness, inequality of opportunity, and low institutional quality and corruption all being associated with lower life satisfaction [11]. Indeed, outcomes of institutional change and policies should not only be assessed by GDP per capita. Institutional “improvements” could be achieved, but still be associated with social disappointment. In particular, outcomes perceived as unfair are problematic, as oligarchic structures (especially around natural resources), cronyism, favoritism, or corruption can lead to societal cynicism and dissatisfaction.

Many early economic reforms were successfully implemented by economic technicians, who—often out of necessity—focused on regulatory frameworks. The agenda today is thus to tackle the remaining regulatory issues, but mostly to address higher-order institutional quality. Indeed, corruption stands as a barrier to further growth and serves to exacerbate inequality of opportunity. Better institutional quality would thus mean more growth and greater satisfaction with the outcomes of reforms.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank two anonymous reviewers and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The authors also wish to thank the participants in the special panel on transition performances held on Friday September 17, 2021, as part of the 16th EACES conference, for an insightful discussion. This article updates Chapter 12 of “Economics of Institutional Change” (2017), Springer Palgrave Macmillan, with substantial changes.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Elodie Douarin and Tomasz Mickiewicz