Elevator pitch

Immigration is one of the most important policy debates in Western countries. However, one aspect of the debate is often mischaracterized by accusations that higher levels of immigration lead to higher levels of crime. The evidence, based on empirical studies of many countries, indicates that there is no simple link between immigration and crime, but legalizing the status of immigrants has beneficial effects on crime rates. Crucially, the evidence points to substantial differences in the impact on property crime, depending on the labor market opportunities of immigrant groups.

Key findings

Pros

There is no evidence that immigration has caused a crime problem across countries.

Immigrants with good labor market opportunities appear no more likely to commit crime than similar natives.

Making sure that immigrants are able to legally find work appears to significantly reduce their criminal activity.

Cons

Public concern over immigration includes a perception that immigrants increase the level of crime.

Immigrants facing poor labor market opportunities are more likely to commit property crimes.

Author's main message

There is no simple link between immigration and crime. Most studies find that larger immigrant concentrations in an area have no association with violent crime and, overall, fairly weak effects on property crime. However, immigrant groups that face poor labor market opportunities are more likely to commit property crime. But this is also true of disadvantaged native groups. The policy focus should therefore be on the crime-reducing benefits of improving the functioning of labor markets and workers’ skills, rather than on crime and immigration per se. There is also a case for ensuring that immigrants can legally obtain work in the receiving country, since the evidence shows that such legalization programs tend to reduce criminal activity among the targeted group.

Motivation

Immigration is frequently mentioned as one of the most important issues facing politicians in advanced economies. Often this appears to be related to the commonly expressed concern that immigrants harm the labor market prospects of natives. This concern has received substantial, and sometimes controversial, attention in the academic labor economics literature. However, it also reflects a wider concern over the impact of large immigration flows on other aspects of society.

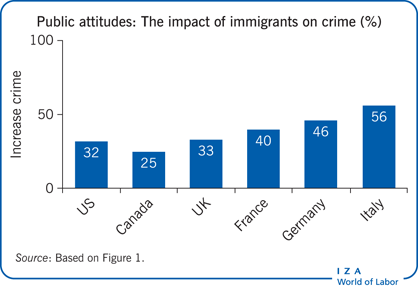

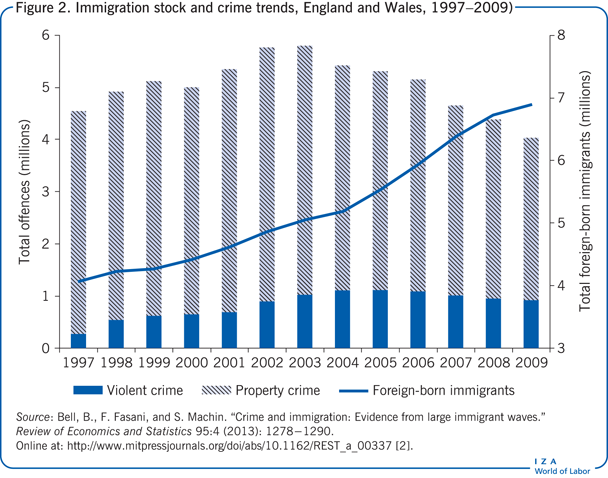

Issues of relevance here cover competition for education and health services, congestion, housing demand, cultural identity, and crime. For example, a large cross-country opinion poll conducted by the German Marshall Fund of the US found similar percentages of natives who thought that immigrants increased crime also thought immigrants took jobs away from natives (see Figure 1).

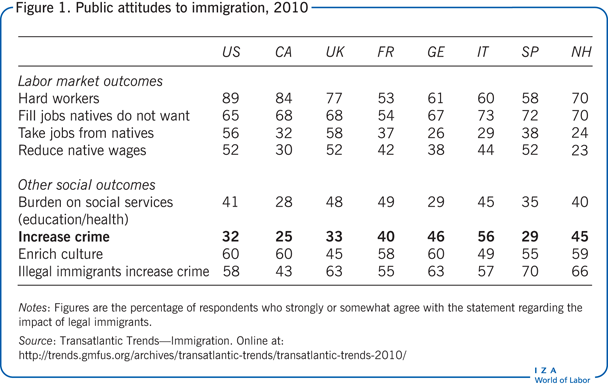

This negative view of the impact of immigrants on crime was particularly strong when the focus was on illegal immigrants. But what is the evidence of any link between crime and immigration? Data from England and Wales show that even though the number of foreign-born immigrants increased significantly between 1997 and 2009, the number of offences—violent crimes and property crimes—decreased noticeably after 2003 (see Figure 2).

Discussion of pros and cons

Framework for analysis

The standard framework that economists use to think about crime is the model developed by Becker [1]. In this model, individuals informally examine their expectations in deciding whether or not to engage in criminal activity. That is, individuals participate in crime if the expected returns from doing so outweigh the expected returns from a competing alternative, usually formal work in the labor market.

This framework is sometimes criticized for implying that all that matters is economic returns. This is not correct. Individuals have different preferences over criminal activity—so there can be some individuals who will simply never commit crime regardless of the economic incentives. The strength of the model is that it makes straightforward predictions regarding how criminal propensity will change as relative returns increase or decrease. There is now a wealth of empirical evidence to support the basic contention that economic incentives do matter for criminal activity.

Why is this framework useful for thinking about the relationship between immigration and crime? There are two principal channels through which the model might suggest different crime patterns between immigrants and natives. The first is because of different relative returns from legal and illegal activity. For example, if immigrants have poor labor market outcomes relative to natives then, all else equal, this will lead to a higher criminal participation rate among immigrants. The second channel is different detection and sanction rates. If immigrants were more likely to be caught or receive a tougher sentence than natives, this might reduce their incentive to commit crime. While both channels are surely important for immigrant−native crime differences, this paper will focus on the first channel simply because of a lack of credible evidence on the second channel.

The evidence base

Three empirical papers from 2013, 2012, and 2011 respectively report causal estimates of the impact of immigration on crime [2], [3], [4]. While there have been many papers that document various correlations between immigrants and crime for a range of countries and time periods, most do not seriously address the issue of causality.

The approach followed by the three papers discussed below is the same as that used to evaluate the labor market impact of immigration: Reported crime data (which do not identify the perpetrator) are used to examine the differences in immigration and crime in local areas within a country. To see how this works, consider two local areas: A and B. The foreign-born share of the population is higher in A than in B. If crime were also higher in A than in B, this could be an indication that immigrants increased crime rates.

However, there could also be other reasons why area A has a higher crime rate than B. For example, high-density areas tend to have higher crime rates, as do areas with more social deprivation. A better approach is to examine whether the change in crime in an area is related to the change in the share of the foreign-born population. This approach controls for any time-invariant characteristics of the area that are potentially correlated with crime rates.

The key remaining problem is that such an estimate might still just capture a correlation rather than a true causal effect. For example, suppose that crime is increasing in an area and the native-born are leaving the area. This opens up housing for incoming immigrants. Thus the foreign-born share of the population rises at the same time at which crime is also rising, but immigration is not actually causing crime to rise in this example.

One possible solution to this problem is to identify exogenous changes in the foreign-born population in an area—changes that are unrelated to other underlying characteristics of the area—and see if these are correlated with changes in crime rates (which involves finding an instrument to measure the exogenous change). In other words, this approach looks for increases in the foreign-born share of the population in an area that could not be related to current conditions in the area and then tests whether crime rises or falls. Such estimates do suggest a causal relationship rather than a mere correlation. They are, therefore, the central focus of this section.

The first of these studies presents estimates of the effect of immigration on crime for England and Wales over the period 2002–2009 [2]. The impact on violent and property crime of two large immigrant flows that occurred over the period is examined. The first was associated with a large increase in asylum-seekers as a result of dislocations in many countries during the late 1990s and early 2000s (including Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and the former Yugoslavia). The second flow resulted from the expansion of the EU in 2004, including the so-called A8: Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

The UK decided to grant citizens from these countries immediate and unrestricted access to its labor market. The study argues that a tighter identification of the impact of immigration on crime can be achieved by focusing on these specific and large immigrant flows. Even here, of course, it must be recognized that there will be considerable heterogeneity within these two flows and that estimates will simply be the average effect on crime.

The study pays close attention to the importance of which instruments were used to disperse the immigrant stocks in order to control for endogenous location choice. For the asylum wave, they make use of the dispersal policy adopted in 2001. From that date, individuals seeking asylum were dispersed to locations around the UK while their claim was being decided. The choice of locations was determined by a central agency with no reference to the wishes of the individual applicant. Thus, the dispersal policy itself can be used as an instrument to explain the locations of asylum-seekers, assuming locations were not chosen as a result of correlation with crime shocks.

For the A8 wave, location choice was entirely up to the individual migrant. However, an extensive literature has established that the prior settlement pattern of migrants from the same national/ethnic group has a strong predictive effect on location choice of future migrants. Assuming that prior settlement patterns have no correlation with changes in current crime rates allows the use of the prior settlement pattern of A8 migrants across areas, combined with aggregate A8 flow data, to produce predicted A8 stocks for each area each year.

The causal estimates in this paper show a detrimental effect of asylum-seekers on property crime, but, in contrast, the effect of the A8 wave on property crime is, if anything, in the opposite direction. There is no impact on violent crime for either immigrant group. Their estimates imply that a one-percentage point increase in the share of asylum-seekers in the local population was associated with a rise of 1.09% in property crimes. A similar rise in A8 migrants reduced property crime by 0.39%.

The authors then go on to interpret these results within the economic model of crime framework. The A8 migrants had strong attachment to the labor market and, indeed, that was the reason for their migration. Asylum-seekers were in general prevented from seeking legal employment in the UK, and the benefits paid to them were substantially less than the out-of-work benefits paid to natives. It thus seems unsurprising that there were different effects on property crime rates from the two waves. It should be noted, however, that in neither case were the effects quantitatively substantial, so most of the decline in property crime witnessed in the UK over the last decade was not related to immigration.

A second study examines the crime−immigration link across Italian provinces over the period 1990−2003 [3]. Estimates show that a one-percentage point increase in the total number of migrants is associated with a 0.1% increase in total crime. When the authors disaggregate across crime categories, they find the effect is strongest for property crimes—robberies and thefts, in particular.

To account for endogenous location choice, the authors use a variant of the prior-settlement pattern instrument used in the previously mentioned study for the A8 migrants [2]. Again, this is shown to be a strong predictor of migrant stocks across localities. The causal results show no significant effect of immigrant stocks on total crime, nor on the subset of property crimes. Thus, the causal effect of total immigration on crime is not significantly different from zero. Unfortunately, the authors do not examine different subgroups of immigrants to assess whether the story of labor market opportunity is in operation here.

The third paper uses panel data on US counties across the three census years 1980, 1990, and 2000 [4]. As with the first two studies, the third reports causal estimates using prior-settlement patterns to identify the crime−immigration relation. Significant effects are found from immigrant stocks on property crime rates but no such effect is revealed for violent crime. The estimated elasticity implies that a 10% increase in the share of immigrants would lead to an increase in the property crime rate of 1.2%. The causal estimates are broadly similar in magnitude, but are much less precisely estimated.

The study then breaks the immigrant stock into Mexicans and non-Mexicans, arguing that this allows the exploration of whether the economic model of crime provides a useful guide in examining the impact of immigration on crime. We know that Mexicans tend to have significantly worse labor market outcomes relative to other immigrant groups in the US. We might therefore expect a more substantial positive coefficient on Mexican immigrants in the property crime regression than on non-Mexican immigrants. This is in fact the case, with the coefficient being significantly positive for Mexican immigrants, while it is negative and insignificant for all other immigrants.

Such a result complements the argument presented in the first study that it makes sense to focus on particular immigrant groups in addition to estimating the overall impact of immigration on crime [2].

Legalizing immigrants

One important determinant of the relative returns to legal and illegal activities for migrants relates to their legal status. Illegal immigrants have much more limited opportunity to obtain legal employment and are rarely entitled to public assistance if they are unemployed. While this suggests that we might expect to see higher criminal propensities among illegal immigrants, it is difficult to evaluate this empirically since we cannot in general observe illegal immigrants. However, two studies have made important progress on this question by examining the effect of policy changes on the legal status of migrants to assess the impact on crime.

The first paper examines the combined impact of clemency granted to prisoners in Italy in 2006 and the expansion of the EU [5]. The Italian legal system frequently resorts to granting clemency to prisoners with less than three years remaining on their sentences in order to reduce prison overcrowding. The 2006 clemency led to 22,000 inmates being immediately released—more than one-third of the entire prison population.

Meanwhile, on January 1, 2007, Romania and Bulgaria acceded into the EU and their citizens were immediately able to legally seek employment in a number of sectors in Italy. Prior to this date they would have been illegal. In contrast, foreigners from candidate EU members (countries being considered for EU membership, for example Croatia) would be illegal both before and after 2007. Thus, the authors propose examining the recidivism rate between Romanians and Bulgarians (the treatment group) and candidate EU foreigners (the control group) released as part of the clemency, but from January 2007 subject to different legal status. A difference-in-difference estimator provides a comparison between relative outcomes pre- and post-legalization.

The authors found a strong and statistically significant reduction in the recidivism rate of Romanians and Bulgarians after the 2007 legalization relative to the control group. During 2007, the recidivism rate for the control group did not change, while it decreased from 5.8% to 2.3% for the treatment group.

Breaking down the data by the type of crime for which the individuals were originally incarcerated, the effect of legalization on recidivism was found to be significant only for economically motivated offenders and not for violent offenders. Furthermore, the effects were strongest in those areas that provided relatively better labor market opportunities to legal immigrants.

While these results are consistent with the economics of crime model, it should be noted that the study’s sample sizes (the share of Romanians and Bulgarians among the total number of inmates released) were quite small. In addition, the authors needed to use various statistical techniques to adjust for different characteristics between the treatment and control groups. This raises the question as to whether the identification of the difference-in-difference estimator is legitimate, since unobserved differences between the treatment and control group could account for the results.

The second paper considers the impact of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in the US [6]. The Act was introduced in response to the rapid rise in illegal immigration during the late 1970s. The legislation imposed harsh penalties on employers who hired illegal immigrants and increased border security, but at the same time provided a near-universal amnesty for illegal immigrants then in the US. Almost three million immigrants were legalized across the US.

Evidence from surveys of legalized migrants suggests strong effects of legalization on labor market outcomes, with 75% of respondents reporting that having legal status made it “somewhat” or “much” easier to find work and 60% reporting that it helped them advance in their current job. Furthermore, wages appear to have been 30−40% higher for those who successfully obtained legal status following the passage of the IRCA. This all suggests that there may be strong effects on crime patterns following legalization.

To estimate the effect on crime, data were collected on both reported arrests and reported crime at the county level each year, which were then matched to administrative data on the annual number of IRCA applicants in each county. A one-percentage point increase in the number of legalized IRCA applicants per capita was found to be associated with a fall in overall crime of 1.6%. Both violent and property crime fell as a result of legalization, though the effect was larger for property crime. An extensive set of robustness checks confirmed the key result that legalization led to reductions in crime.

Immigrant victimization

In addition to the impact of immigration on reported crime, there is also the alternative channel through which crime and immigration may be linked: namely, immigrants themselves may be disproportionately victims of crime. Perhaps any positive correlations between crime and immigration rates in an area actually signal increased crime against immigrants rather than by immigrants. Most research in this area uses self-reported rates of victimization or victim reports from the police. Again, a key difficulty is that if immigrants have different reporting rates than natives (perhaps because they are more cautious in having contact with the authorities), it will be difficult to identify the true differential in victimization between natives and immigrants from the reported differential.

Data from UK crime surveys have been used to estimate probability models of self-reported crime victimization [2].

Controlling for an extensive range of individual covariates, it was found that immigrants are less likely to report being victims of crime than natives. This is true for all immigrants, as well as for the two waves of immigrant inflows (asylum-seekers and migrants from the A8) that were the focus of the paper. This raises an interesting question about why immigrants appear to be less exposed to crime. One possibility is that immigrants have moved into neighborhood clusters that provide a natural protection against crime, particularly if immigrant-on-immigrant crime is viewed as socially unacceptable.

Another study collected data from German newspapers on reports of violent attacks against foreigners [7]. It found significant differences in the patterns of violence in the East and West of the country, with the incidence of anti-foreigner crime higher in the East and rising with distance from the former West German border. The experience of immigrants in Sweden has also been explored, with evidence suggesting that immigrants are more exposed to violence and threats of violence than native Swedes [8]. Interestingly, second-generation immigrants appear to be most exposed.

Controlling for individual characteristics, second-generation immigrants are 30% more likely to experience violence than indigenous Swedes. The gap is a result of higher levels of violence in the street and other public places and higher rates of domestic violence against women. In contrast, in Switzerland, it has been reported that immigrants have broadly similar victimization rates to natives [9]. It is hypothesized that this may be a result of the lower concentration of immigrants in poor neighborhoods than in some other countries.

There appears to be no consistent pattern of immigrant victimization across countries. However, it does seem that violence against immigrants is much more likely in poor areas in which immigrants have rapidly become a substantial and visible minority in previously homogenous communities. The neighborhood does seem to be important in this context.

Limitations and gaps

In spite of the set of empirical studies discussed above, there is still surprisingly little convincing evidence on the crime−immigration link. Part of the reason for this is the need to overcome the difficult identification issue. If we find a correlation between crime and immigration, is it because immigrants cause the rising crime or because immigrants move into areas that are experiencing rising crime levels (for example, because housing has become cheaper in those areas)? The studies this paper focuses on pay particular attention to this issue and, as a result, provide more credible evidence.

The small number of studies that have focused on different immigrant groups rather than estimating the average effect of immigration on crime have pointed to the importance of labor market opportunities. This is likely to be a continued focus of research across countries with very different immigrant groups. In addition, other aspects of the criminal justice system deserve attention. This will include a deeper understanding of the relative probabilities of immigrants and natives being arrested, charged, convicted, and sentenced for different crimes. However, it is likely that data issues will make many of these investigations hard and inconclusive.

Summary and policy advice

The evidence points to the labor market as a key determinant of the likelihood that immigrant groups will engage in criminal activity. In many ways, this is no different than for natives. There is extensive evidence that poorly educated, low-skilled natives will be more likely to commit crime than otherwise identical high-skilled, stably employed natives. Thus, policies that focus on improving the employability of workers—natives and immigrants alike—will have the added benefit of reducing crime.

However, policymakers have two additional tools at their disposal when focusing on immigrants and crime:

First, legalizing the status of immigrants appears to have beneficial effects on crime rates—a rarely discussed aspect of such programs.

Second, the increased use of point-based immigration systems allows countries to select the characteristics of immigrants that are offered residence.

Thus, for example, Canada and Australia both operate point-based systems for certain immigrants that award points to potential migrants on the basis of characteristics such as education, work experience, age, and employment plans. There is then a threshold of points that must be reached before legal immigration is possible (see [10]). Such systems allow countries to change the profile of immigrants by altering either the points awarded for particular characteristics or the threshold required to gain entry.

Thus, the evidence above suggests that to the extent that countries worry about the crime effects of immigration, they can tilt the offer they make in the international immigration market by awarding more points to those with high skills, a job offer, and a high wage. Such a policy is in any case being pursued by many countries for a range of other reasons.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks three anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Support from the Max Planck Institute of Religious and Ethnic Diversity and Massey University is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Brian Bell