Elevator pitch

The Mincer equation—arguably the most widely used in empirical work—can be used to explain a host of economic, and even non-economic, phenomena. One such application involves explaining (and estimating) employment earnings as a function of schooling and labor market experience. The Mincer equation provides estimates of the average monetary returns of one additional year of education. This information is important for policymakers who must decide on education spending, prioritization of schooling levels, and education financing programs such as student loans.

Key findings

Pros

Earnings can be explained as a function of schooling and labor market experience using the Mincer equation; this provides policymakers with important information about how to invest in education.

Due to the comparability of Mincerian results, individuals can make use of these results to help guide their personal decisions about how much schooling they should invest in.

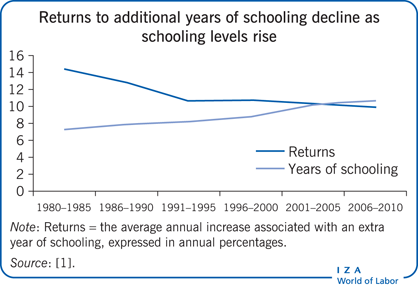

Recent studies using the Mincer equation indicate that tertiary education, as opposed to primary education, may now provide the greatest returns to schooling; this represents a shift in the conventional wisdom.

Cons

The relationship between schooling and earnings does not necessarily imply causality.

Earnings functions provide private (i.e. individual) returns to schooling, whereas government/public costs and other benefits are needed to estimate social rates of return.

As economies become more complex and technological developments alter the demand for education, decades-old cross-sectional data may not be informative about returns to current investment decisions.