Elevator pitch

Unemployment insurance can be an efficient tool to provide protection for workers against unemployment and foster formal job creation in developing countries. How much workers value this protection and to what extent it allows a more efficient job search are two key parameters that determine its effectiveness. However, evidence shows that important challenges remain in the introduction and expansion of unemployment insurance in developing countries. These challenges range from achieving coverage in countries with high informality, financing the scheme without further distorting the labor market, and ensuring progressive redistribution.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployment insurance can increase the formalization of jobs; in turn, formal jobs may become more valued by workers, and it enables a more efficient job search.

Unemployment insurance can be a better tool to provide income support during unemployment than other instruments, e.g. severance payments.

Evidence shows that, even in developing countries, unemployment insurance facilitates consumption smoothing.

Cons

Unemployment insurance coverage will be low in countries with a large informal sector and will probably not cover those most in need.

In countries with high levels of informality and worker turnover, unemployment insurance may transfer resources from low-income to high-income workers.

Moral hazard concerns are more pernicious in countries with high informality, as workers can claim benefits and keep working informally.

There is no evidence that job seekers receiving unemployment insurance find better (formal) jobs.

Author's main message

The introduction (or expansion) of unemployment insurance in countries with large informal sectors could, in principle, both insure workers against unemployment spells and help create formal jobs. Unemployment insurance will be more effective if workers value the benefits it provides, if it has relatively limited costs for firms, and if it is complemented with active labor market policies that reinsert the worker into a formal job. However, issues of coverage, efficiency, and redistribution are potentially more salient in countries with large informal sectors, and should thus be addressed when implementing unemployment insurance.

Motivation

Most workers in developing countries work in unregulated jobs with no access to basic benefits such as health insurance, worker compensation, death and disability insurance, or retirement pensions. They are normally called the “informal” workers, whereas “formal” workers are those covered by formal social security programs. The existence of large informal sectors impacts the way in which public policies can be implemented and how they affect the labor market. Unemployment insurance is one such policy.

Unemployment insurance is a risk pooling arrangement that aims to provide workers with consumption smoothing (balancing their living needs and their assets) during unemployment spells and facilitate their search for new jobs. These programs are prevalent in high-income countries. While unemployment insurance programs share similar objectives and trade-offs in developing countries, they also change incentives to comply with labor and social security regulations. In other words, unemployment insurance alters the relative prices of holding a formal versus an informal job. Depending on how it is financed (e.g. workers, firms, or government contributions) and how much the insurance arrangement is valued by workers, unemployment insurance can be a key element for increasing social security compliance and for creating formal jobs.

However, the implementation or extension of unemployment insurance schemes in developing countries poses several additional challenges because of the existence of large, overdeveloped informal sectors. The three main problems are: efficiency, coverage, and redistribution.

Recently, substantial research has been aimed at understanding the effects of unemployment insurance in labor markets with a high share of informal jobs (i.e. jobs that are not officially reported and that do not contribute to tax or social security systems). Using the Latin American experience, where fewer than 50% of jobs are formal, serves as a good example to highlight the opportunities and challenges of unemployment insurance in such countries.

Discussion of pros and cons

Unemployment insurance schemes traditionally require mandatory contributions from active workers in exchange for a limited stream of income if they involuntarily lose their jobs. These schemes are relatively uncommon in developing economies with large informal sectors. Introducing such schemes can provide consumption smoothing (i.e. reducing the drop in consumption in periods of low or no income) for formal workers during unemployment and facilitate a more efficient job search. In high-income economies, unemployment insurance schemes pose many challenges, including the potential reduction of job search efforts. Similar issues apply to labor markets in developing countries. However, other issues are particular to developing countries with large informal sectors, such as the lack of proper coverage, incentives to search for formal jobs before and after a period of unemployment, and regressive redistribution of income from workers that contribute to the unemployment insurance scheme, but have not done so long enough to reach the vesting period, to those that are eligible for benefits.

Some of these issues can be ameliorated if income support is based on unemployment individual savings accounts (UISA), which have been introduced in countries like Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador. Under this design, workers accumulate savings in an individual account that is accessible once an involuntary unemployment spell starts. Solidarity components, which complement individual savings and provide insurance, can be built in as the funds are depleted. These features are aimed at minimizing unemployment insurance’s impact on workers’ incentives to obtain a formal job. Moreover, individual accounts serve to reduce redistribution, since, in its pure form, during unemployment insurance saving accounts finance unemployment spells with savings.

Efficiency and the net effects of unemployment insurance on labor markets

Although intimately related, it is useful to consider two main ways in which an unemployment insurance scheme affects labor markets with large informal sectors. First, on the demand side, unemployment insurance affects the type of jobs that are created (formal versus informal) and, second, it alters the incentives to search for and accept a formal job after an involuntary unemployment spell.

In this context, unemployment insurance provides an entitlement that is contingent on the worker’s contribution to the scheme while employed in a formal job for a predetermined period of time [2]. The fact that contributions only occur while employed formally creates a tradeoff between the size of the worker’s contribution against the generosity of the entitlement they receive when eligible. This tradeoff determines the incentives for firms to create formal jobs and for workers to accept a formal sector job offer. From the worker’s perspective, as the entitlement of the unemployment insurance with respect to the contribution rate increases, so does the worker’s incentive to obtain a formal sector job. From the firm’s perspective, unemployment insurance imposes additional costs, depending on how it is funded. Additionally, if workers sufficiently value the scheme then they will exert more effort when looking for formal jobs. In a context of high informality, where firms can decide the types of jobs that are officially posted, firms might be more inclined to offer formal jobs if there are more workers looking for those types of jobs.

The second mechanism is set in motion as workers qualify for unemployment insurance, since some workers in the informal sector can enjoy both insurance benefits and nontaxed wages, in so far as workers are not discovered holding informal employment by the government. This implies that once workers qualify for unemployment insurance collection, strong incentives exist for them to move to the informal sector. This creates a push toward fewer formal jobs in the economy as a whole [2].

The alternative argument is that once a worker is receiving unemployment insurance, a more efficient job search can be conducted, which leads to a higher probability of formal job offers. The relative strength of these mechanisms determines the overall change in unemployment and the share of formal versus informal employment that results from the introduction (or extension) of an unemployment insurance system.

Overall, the net welfare effect of unemployment insurance appears to be ambiguous. On the one hand, these schemes provide insurance that redistributes resources from employed to unemployed workers, something that might be desirable. Additionally, they might lead to a more efficient search for formal jobs. On the other hand, there are efficiency costs, as workers might reduce job search efforts and delay their re-entry into the formal labor market, or stay away from the formal sector altogether in order to keep receiving insurance benefits. In countries with large informal sectors, there are additional possible increases or decreases in welfare. In particular, the final allocation of workers into formal or informal jobs has a direct effect on how much tax can be collected, while the overall effect on an economy’s productivity is uncertain.

There is a series of theoretical papers that analyze unemployment insurance’s effects in the context of informal jobs. Overall, when these models are calibrated, they unsurprisingly show that the higher the expected benefits are relative to the costs, the stronger the effects for formalization are (i.e. the economy becomes more formalized).

A calibration exercise for Mexico shows that raising the level of the benefit for a given contribution increases a worker’s incentive to remain in the formal sector so that they can qualify for collection [2]. At the same time, this scheme reduces informality while increasing unemployment (as the value of being unemployed increases due to the existence of the unemployment insurance benefits). On the other hand, if the required contributions increase while the benefits remain unchanged, then the program becomes less attractive, as does being formally employed, thus leading to an increase in informality [2].

Similarly, another calibration exercise shows that an unemployment insurance system in Malaysia would slightly increase the unemployment rate if benefits were not overly generous. However, the system would induce a reallocation of labor from wage into self-employment, though the expected effects are relatively modest [3].

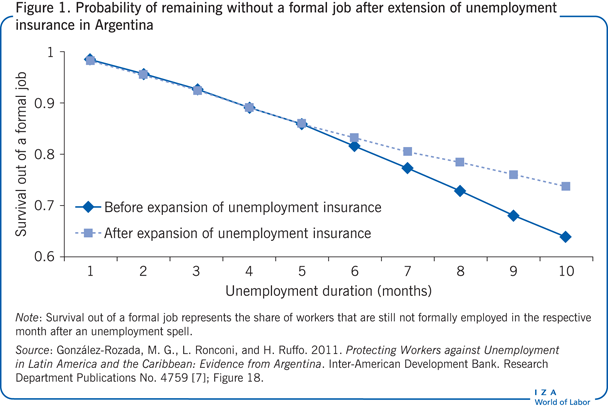

The empirical literature mainly focuses on what happens to workers’ re-entry probabilities (i.e. their likelihood of re-entering the formal labor force) as unemployment insurance systems are implemented or expanded. Many papers have shown, convincingly, that more generous or longer benefits lead to a lower probability of returning to a formal job, as for example in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay [1], [4], [5], [6], [7]. So, it seems that potential efficiency gains related to a better job search process are outweighed by reduced search efforts and/or a transition toward informal jobs (Figure 1).

Further results from the literature suggest that the effects of an increase in the benefit amount are not equivalent to an increase in the benefit duration. In both cases, evidence indicates that the duration of non-formal employment (that is being unemployed or employed informally) will increase; however, an increase in the benefit amount has less of an impact than increasing its duration. In Argentina, increasing benefits by around 10% has a smaller impact on the re-employment rate than when extending the benefit by one month (i.e. the re-employment rate into formal jobs does not drop as much when increasing benefit amounts), while the government incurs similar fiscal costs for both options [6].

Furthermore, the evidence available suggests that this longer duration in unemployment does not lead to a more efficient job search. Studies that analyze an increase in unemployment benefits [6], or an extension in the duration of benefits [4], find no difference in re-employment wages for those workers exposed to higher benefits compared to those exposed to lower benefits.

One interesting finding from Brazil is that the efficiency cost related to longer benefit duration (i.e. the costs due to workers not re-entering formal sector jobs because they receive insurance benefits) actually increases with the share of labor market formality. This indicates that efficiency problems may be more salient in higher formality labor markets (understood as cities or regions). Workers may take advantage of the situation by obtaining informal jobs that they would not have obtained in the absence of unemployment insurance. In other words, when workers receive unemployment benefit for longer periods of time, they are more able to earn additional income during the benefit period via an informal job, which represents an efficiency cost associated with unemployment insurance schemes.

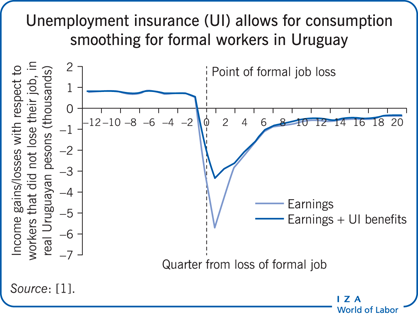

The existence of efficiency costs does not imply that unemployment insurance in developing countries necessarily leads to negative welfare effects. The efficiency cost must be weighed against potential gains, namely the provision of consumption smoothing for the unemployed. For instance, in Uruguay (where 30% of workers are still informal), one month after the loss of a job, the average loss in income for workers who did not have access to unemployment insurance was 39%, in contrast to only 13.5% for those who did have access (see Illustration) [1]. In fact, some argue that the efficiency cost of people shifting to informality is relatively small compared to the welfare gains, at least when examining the Brazilian context [5]. This is due to the fact that only a very small fraction of the cost of (longer) unemployment insurance benefits is caused by workers not returning to formal jobs.

Informality and the issue of coverage

It is likely that most unemployed workers in developing countries lack any kind of unemployment income support. There are essentially two reasons for this: First, many developing countries do not have unemployment insurance systems in place. And second, these systems typically perform poorly in those developing countries that have adopted them.

Perhaps the primary challenge when implementing an unemployment insurance system in countries with large informal sectors is that relatively few people would contribute and thus qualify for the benefits due to the relatively low proportion of formal employment in the labor market. Usually, the self-employed, who make up a large portion of the informal sector, do not have to contribute to unemployment insurance schemes. In Latin America, around one-third of the labor force is either self-employed or owns a small firm.

This situation is compounded by the fact that a large share of those who become unemployed are informal workers. In Mexico and Brazil, around two-thirds of newly unemployed persons actually originate from informal jobs [8]. Furthermore, given the high rate of transitions between formal and informal jobs, many workers who lose formal jobs will not have access to unemployment benefits because they did not hold the formal job long enough to qualify due to frequent switching between formal and informal sectors. Although eligibility rules vary across countries, unemployment insurance schemes normally demand a minimum number of contributions in the period immediately before the unemployment spell. However, due to a high transition rate between job types, countries with large informal sectors tend to permit less consistent contributions. Simulations using administrative data for Mexico and Uruguay show that between 30% and 70% of formal workers that lose a formal sector job would not quality for unemployment insurance [9]. This also illustrates the extent to which workers are unlikely to assign much value to unemployment insurance systems given that they probably will not qualify for benefits.

Unemployment insurance coverage is and will probably remain one of the key limitations of in countries where informality is widespread. This lack of coverage is important, not only because workers and their families in the region are vulnerable to unemployment risks, but also because it highlights an underlying and more profound problem: the low productivity of many jobs in these countries. That is, the jobs that are created in developing countries are not productive enough to make it profitable for the firm (and the worker) to pay the social insurance contributions, which may include unemployment insurance contributions that are mandatory for formal workers. Hence, any scheme that is financed through employee-employer contributions will suffer low coverage rates in developing countries.

Unemployment insurance and redistribution

One key aspect of unemployment insurance is that it acts as a redistribution mechanism, transferring income from those who are employed to those who are unemployed. In principle, this is desirable because the extra dollar is more “valuable” for the unemployed than the employed. However, given the weak coverage patterns in countries with large informal sectors, this redistribution might not always be desirable. Many workers who contribute to the unemployment insurance scheme will not accumulate enough contributions to qualify for unemployment insurance benefits if/when they lose their formal jobs (primarily the low-income and low-skilled workers). Those who contribute and do qualify for benefits will probably come from the higher end of the income distribution spectrum. Therefore, in some cases (depending on the coverage), unemployment insurance might actually redistribute income from low-income employed persons to unemployed middle or high-income workers.

Vesting periods (the number of contributions necessary to qualify for unemployment insurance) are at the root of this redistribution issue. Indeed, they are sometimes too long for low-income workers who frequently rotate out of formal and into informal jobs. For instance, Ecuador requires two years of contributions, while Uruguay and Venezuela require 12 contributions in the two years prior to the unemployment spell. Argentina is relatively more lax; it requires 12 contributions in the previous three years. In all, long vesting periods will ensure that very few workers who lose their job will ever be able to take advantage of unemployment insurance benefits. In Brazil, the country with the highest coverage in Latin America, only 13% of currently unemployed people receive unemployment insurance, compared to rates in the US (28%) and Canada (40%) [9].

UISA designs might reduce the redistribution issue, as the unemployment spell is financed though the worker’s own savings. However, as long as an insurance component requires a vesting period for eligibility, similar redistribution might occur. In Chile, for instance, in order to access the solidarity fund, 12 contributions in the previous 24 months are required. Furthermore, the last three contributions must have been with the same employer.

In all, before implementing or expanding unemployment insurance in countries with high informality, it is important to understand the extent and flow of the expected income redistribution. A high rate of rotation out of formal jobs, which is common in countries with large informal sectors, will probably exacerbate redistribution issues.

Unemployment insurance and interaction with other instruments

In a well-designed social protection system, unemployment insurance should be combined with other instruments that promote an early return to a formal job. Given unemployment insurance’s role as a mechanism to help facilitate an effective job search, proper integration between this scheme and active labor market policies, such as training programs and better intermediation between firms and workers, is highly desirable. This may be particularly important in developing countries, since moral hazard concerns could be more acute given the higher proliferation of informal work. Proper monitoring through connecting unemployment insurance with public employment services aimed at re-entry into the formal labor market might reduce this risk. Unemployment insurance can help mitigate some of the problems that other traditional instruments encounter when providing income support. Determining which set of instruments is most effective greatly depends on the country context.

Perhaps the oldest way in which workers have been protected against unemployment is through severance payments, which predate the development of pension and unemployment insurance systems [10]. In principle, severance payments fulfill a similar role to unemployment insurance, by providing the newly unemployed with some income support that can help facilitate a better job search (e.g. by providing the unemployed person with the financial means to search for jobs that better match their profile, rather than having to take the first available job). However, there are important differences. Severance payments provide a one-time payment (normally relatively high compared to what an individual would receive from unemployment insurance), which is not distributed throughout the unemployment spell. This means that severance payments might not generate sufficient consumption smoothing for the worker. Furthermore, risk pooling with this instrument only occurs at the firm level, rather than with all employees in the labor market. Severance payments are also very difficult for workers to enforce, and if sufficiently high, they might discourage formal job creation, particularly if labor legislation remains ambiguous as to what a legitimate reason for dismissal is. Unemployment insurance can improve some of these deficiencies, particularly in developing countries, as it is able to provide better consumption smoothing and more efficient risk pooling. Workers that qualify for unemployment insurance start receiving payments immediately, and it is less litigious, which gives both firms and workers a good estimate of the cost of the instrument.

Nevertheless, severance payments play an important role in a well-organized employment protection system; for instance, they help firms internalize the full social costs of dismissing workers. At the same time, they suffer similar problems of coverage as unemployment insurance, but for different reasons. In practice, many workers that qualify for severance payments do not end up receiving any payments, which reduces the effectiveness of this tool. For instance, in Argentina, only 32.4% of workers who were eligible for severance payments actually received them. In Mexico, 20% of workers immediately received the payment, while 39% never received anything [9]. This could be due to the fact that severance payments are often owed during moments of crisis, when firms have limited capacity to absorb the additional costs of making workers redundant.

Theoretical papers point to the fact that unemployment insurance can partially or totally replace other means of protecting workers, such as severance pay, while still having positive impacts on labor formality [2]. Some papers study how unemployment insurance affects incentives to take formal jobs in combination with other interventions. The literature shows that there is plenty of scope for policy complementarity. For instance, introducing an unemployment insurance system while lowering severance payments, lowering employment taxes, or increasing government monitoring of the informal sector can reduce the negative effects on formality caused by the introduction of an unemployment insurance system. However, the political realities of combining instruments are very complex.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that, given unemployment insurance’s limited coverage in developing countries, other instruments have been developed to provide unemployed workers in these countries with income support (regardless of whether they are formal or informal workers). Temporary employment programs have been in use throughout Latin America to specifically target informal workers that become unemployed. These programs have very limited eligibility criteria and have generally proven successful at providing some consumption smoothing for workers who are not reached by typical unemployment insurance systems. However, these programs do not manage to effectively reintegrate workers into the formal labor force once the program is finished. There is also some evidence of negative effects associated with the stigma of participating in these temporary programs, leading to low participation rates [9].

Limitations and gaps

Empirically, there is still much to learn about this topic. The question of how different unemployment insurance parameters affect the level of formal jobs is still not answered empirically, especially not with respect to developing countries with high informality rates. Efforts should be directed at understanding these general (equilibrium) effects on the overall level of formality. This might be particularly relevant, as the introduction of unemployment insurance and its consequences for labor market formality has a direct impact on a government’s budget.

Much more could also be done to understand how workers and firms value unemployment insurance arrangements, and how much they are willing to pay for them. Evidence suggests that Brazilian workers are willing to accept lower formal wages in exchange for access to some of the benefits of the social security system [11]. However, several social protection surveys suggest that, apart from health services, workers place very little value on the benefits from social insurance components, such as pensions [9].

In addition, more research is needed to determine the right balance between savings and insurance, especially in the context of individual savings accounts aimed at funding unemployment spells in countries with high informality. From the welfare perspective, there is a need to better understand the redistribution effects that occur within unemployment insurance systems, especially considering different levels of informality. Moreover, it is important to evaluate the fiscal and productivity implications of shifting workers from formal to informal jobs.

Finally, more empirical work on the interaction between unemployment insurance and other instruments, such as active labor market policies, severance payments, and temporary employment programs is needed in order to guarantee adequate income support for the unemployed, facilitate efficient job searches, and to develop an environment where greater numbers of formal jobs are created.

Summary and policy advice

Unemployment insurance is a social insurance program that, if sufficiently valued by workers and designed with appropriate parameters, such as the amount, eligibility criteria, and length of vesting period, can be a good instrument to both provide income security for workers while unemployed and increase a country’s level of formality. However, so far the evidence has shown that existing unemployment insurance systems in developing countries increase unemployment duration and/or informality. Furthermore, in a context of high informality, these systems seem unable to reach most workers. In fact, benefits mainly reach workers that are already relatively protected, which, in some cases, can lead to a redistribution of income from low- to high-income workers.

Unemployment insurance could be a viable option for developing countries with relatively high levels of formality and that have well-developed active labor market policies. This type of insurance would offer important advantages over existing instruments such as severance payments; including, among others, better risk pooling among workers (i.e. workers who do not lose their jobs subsidize those who do) and more effective consumption smoothing during recessions. However, these countries are also potentially the ones in which the unemployment insurance efficiency costs will be highest. In this context, helpful steps include designing mechanisms with decreasing payments, or that provide a bonus for rapid re-employment, like in Korea (which provides salary subsidies if wages are below those of the previous job), as well as linking unemployment insurance with other labor market policies.

The main policy advice regarding unemployment insurance in contexts of high informality can be summarized as follows:

Benefit design should target re-entry into the formal sector, perhaps conditioning the receipt of some additional benefits on obtaining a formal job or by allowing decreasing payment schemes.

The benefit amount should be sufficiently small and should include a maximum duration to reduce moral hazards (i.e. situations where workers or firms take advantage of the system). However, this step will make it more challenging to smooth consumption.

Implementation and extension of unemployment insurance systems should be considered in tandem with other competing instruments already in place in a particular country. For example, substituting all or part of severance payments with the introduction of unemployment insurance systems could be a good way to improve the protection of workers against unemployment risks while promoting the creation of formal jobs.

Finally, unemployment insurance should be developed in parallel with a strengthening of active labor market policies. Active labor market policies, such as training programs, temporary jobs programs, or job subsidies, provide better coverage because they do not require past contributions in the formal labor market, although there are also concerns about these programs’ effectiveness [12]. This is particularly useful because well-developed and integrated active labor market policies can reduce moral hazard problems commonly associated with unemployment insurance schemes, which are more acute in highly informal labor markets.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author (together with Esteban-Pretel [2], and Alaimo, Kaplan, Pagés, and Ripani [9]) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Mariano Bosch