Elevator pitch

It is not possible for a formal employment contract to detail everything an employee should do and when. Informal relationships, in particular trust, allow managers to arrange a business in a more productive way; high-trust firms are both more profitable and faster growing. For example, if they are trusted, managers can delegate decisions to employees with confidence that employees will believe the promised rewards. This is important because employees are often better informed than their bosses. Consequently, firms that rely solely on formal contracts will miss profitable opportunities.

Key findings

Pros

Formal employment contracts are incomplete, necessitating informal agreements to fill the gaps; these informal agreements rely on two-way trust between managers and employees.

Trust comes from individual relationships between an employee and their managers, managerial reputation, and social norms.

Trust allows for more effective task allocation and organizational structures, which can allow firms to better utilize employees’ knowledge and skills, aiding profitability.

Competition in the product market can engender higher levels of trust within organizations, as competition spurs firms to be more productive.

Cons

Market downturns can cause trust to be broken, as managers find it harder to keep past promises in tough times.

External negative shocks mean that trust tends to be lost over time, rather than earned.

Labor mobility makes trust more difficult; shorter employment relationships reduce the reputational costs to managers from breaking their word.

Trust is difficult to manage in organizations because it is the combination of social norms, managerial practices, and individual relationships.

Author's main message

Delegating authority can make firms more productive and profitable, as employees are often better informed than managers. Managers must be able to trust that employees will not misuse their autonomy, and employees need to trust that managers will keep their promises. If they are trusted, managers can delegate decision-making to employees with confidence that a promised future reward will be sufficient to appropriately motivate them. Consequently, trust is an important input into running a firm well. One policy option to facilitate better-run firms is to promote management training programs, much like a modernized version of the state-sponsored training programs offered in the US in the post WWII period.

Motivation

Making informed decisions is vital for business success. As it happens, employees often have knowledge that their managers lack. Moreover, given its idiosyncrasies and complexity, this knowledge is often difficult to communicate in a clear and timely manner. Good decisions in this environment require delegation. Herein lies the problem—delegation provides (non-owner) employees with the opportunity to take decisions that are in their own interests, not the firm’s. For example, they might advocate for their pet project (perhaps one that requires little effort), not the profitable one. Managers, given this potential issue, might be hesitant to delegate to an employee, even if that employee is better informed.

If a manager could write and enforce a detailed contract that specifies all contingencies when delegating authority, a firm could protect itself from employee self-interest. However, this is typically not possible, particularly in complex and rapidly changing knowledge industries. For their part, too, as the arbiter on an employee's performance, managers often have scope to renege on promises of incentive pay.

How do managers deal with this quandary? To answer such a question, it is worthwhile to explore how trust between employees and management can supplement formal contracts by making promises credible. When trust exists, managers and employees can organize firms in ways not possible otherwise, such as delegating decisions to better informed employees, thereby increasing profitability and benefiting all parties. Given the benefits of trust, managers face the challenge of how to engender and retain it in their organizations. This is difficult because the accumulation of negative shocks over time can force managers to break their past promises, which erodes trust.

Discussion of pros and cons

Employment contracts are incomplete, necessitating trust between employees and managers

The formal terms of employment are typically established when someone starts a job, and this formal contract is generally renegotiated infrequently. Employment contracts, moreover, usually set out basic expectations about both the work to be done and the pay, leaving many aspects of an employee's job—and even the way incentive pay will be determined—outside the formal obligations of both workers and management. It really cannot be any other way. In a fast-paced modern economy, what an employee should be doing, and how, changes constantly. This means that in many crucial ways, employment contracts are incomplete. Incomplete contracts also arise because it is difficult to describe in an unambiguous way what should be done, and what constitutes good performance. Performance evaluation is notoriously subjective—did an employee hit their key performance indicators (KPIs)? Was performance above the standard required for a bonus, as assessed after-the-fact by the manager? How does a manager weigh the different contributions of team members to the overall success of a project? Subjectivity in performance evaluation provides managers with significant discretion in the approval (or otherwise) of incentive rewards in many organizations.

Incomplete contracts mean that firms need to rely on informal agreements with employees (also called implicit contracts) to fill these gaps. For example, a manager might promise to pay a bonus to an employee for excellent performance on a delegated task. The problem is that a promise like this sits outside of any legal obligations. Consequently, to have any traction, an employee must trust that the manager will honor what they have promised. Similarly, to be willing to delegate responsibility, a manager needs to trust that an employee will not take advantage of their delegated authority. In this way, trust is a two-way street; an informal agreement needs managers to trust their employees, but it also needs employees to trust their managers.

Trust comes from relationships, reputation, and social norms

If an informal agreement between management and an employee is to function, both parties must trust that the other will adhere to the agreement, even though there is no legal sanction from not doing so. For this to be the case, an implicit contract needs to be self-enforcing, in that both parties want to honor it. In this way, trust can develop even if managers and employees are totally self-interested.

Trust can arise in different ways. An ongoing employment relationship can facilitate trust. This is because if a manager (for example) reneges on a promise, the employee can “punish” them in the future by being generally non-cooperative (and vice versa). This future punishment could include the employee working-to-rule or refusing to partake in any informal agreement again. In this context, trust between a manager and an employee is possible when the future rewards from adhering to an informal agreement exceed the short-term benefits from breaking it for both the manager and the worker. Empirical evidence from a 2020 study suggests that trust depends on the specific dyad relationship between a manager and an employee [1]. Indeed, employee trust of management varies considerably within establishments, suggesting that there are not just high-trust or low-trust firms and that individual employee–manager relationships matter significantly.

A reputation for being trustworthy might be another way to ensure that a manager or an employee keep their promises. As an example, there could be a short-term benefit to a manager from reneging on a promise, like not having to pay a bonus. But such a course of action might mean they earn a reputation as being someone who cannot be trusted. This means that other workers will be less likely to trust this manager's promises in the future, limiting the opportunities for a manager to rely on informal agreements from that point on. If these reputation costs are large enough, a manager will opt not to break the promise. A 2019 study finds that reputational effects are particularly strong for firms named after the family running the firm [2].

Any economic transaction occurs in a broader context in which there are customs and social expectations. The same holds for dealings between managers and employees. In some cultures, the social sanctions (or psychic costs) of breaking a promise could be quite high—high enough in fact to dissuade someone from breaking a promise, even if they have some incentive to do so [3].

These separate sources of trust—relationships, reputation, and social norms—need not be mutually exclusive. Indeed, these different mechanisms may help reinforce trust between employees and managers in a business.

Trust facilitates delegation

Trust affords a manager the opportunity to use an informal agreement with an employee, not having to rely exclusively on formal—legal—contracts. As noted above, modern business is too fast moving and often too complicated to have everything detailed in a formal contract. Being able to make informal agreements with an employee aids flexibility and can make the firm more productive and profitable.

For instance, firms located in countries with higher levels of trust are larger than their counterparts located in countries with lower societal trust [4]. As a business grows, monitoring of employees becomes more difficult. Trust provides managers greater assurance that employees will not take advantage of this and will, rather, do what is expected of them. The ability to grow the size of a firm has many advantages, such as realizing scale economies; larger firms are typically more productive than smaller ones. Similarly, there is evidence of a positive relationship between a firm's financial performance and the average integrity/trustworthiness of its managers, as assessed by employees [5].

Not having to rely on formal contracts allows for any number of more productive arrangements, but one of the most important is that trust facilitates delegation of decision-making authority when it would not otherwise be possible. Effective decision-making can make all the difference to a firm, and this requires making the best use of the information that resides within the organization. It is infeasible for managers to be fully informed about all decisions. Moreover, often employees are better informed—they typically have the technical expertise or interact directly with clients. This information should be incorporated into the decision-making process, but it can be difficult to communicate this complex and time-sensitive information to a manager. Instead, a more direct method of using this knowledge is to delegate decision authority to employees.

Of course, delegation comes with its own problems. If a manager delegates to an employee, how do they know that the employee will not take advantage of this decision-making power for their own ends? Furthermore, even if an employee does the right thing, making decisions to increase profit, how does an employee know that their manager will evaluate and reward them fairly? This is where trust is valuable. With trust, a manager can be confident that a worker will not misuse their decision-making authority but rather use their information and skills appropriately. Critically, also, with trust a worker will be reassured that a manager will keep their promise of any future reward owing to the worker if they do the right thing. As noted, two-way trust makes such an informal agreement feasible. Trust then allows for effective use of employee knowledge not possible without it, aiding effective decision-making and increasing firm profitability.

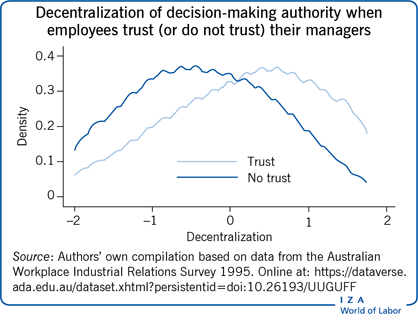

There is now strong empirical evidence linking trust to delegation. For instance, a study from 2012 finds that establishments in high-trust countries, such as the US, and subsidiaries of manufacturing firms based in high-trust countries, are more likely to decentralize decision-making authority to the plant level from headquarters [6]. Similarly, another recent study finds that delegation is higher in regions with high social capital [7]. The previously cited 2020 study finds that employee trust of management is very much an individual characteristic—employee trust of managers at their workplace can vary considerably [1]. This suggests that managers need to work on trust at the individual level, rather than relying on societal trust or an overall high level of trust in a particular business. Secondly, the authors find that higher levels of an employee's trust of their managers facilitates greater delegation of authority to that employee. This result is shown in the Illustration. The figure plots the distribution of delegation for employees who either: (i) trust their managers; or (ii) do not trust their managers, in a survey of Australian employers and employees. There is a significant rightward shift of the distribution of those employees with trust in management, indicating greater delegation of authority to employees who trust their managers.

Competition in the product market can engender trust in organizations

A business does not exist in a vacuum; all firms will respond to their external environment, both in terms of their business strategy and their internal structures. Some firms have limited product-market competition, whereas others face strong competition from their rivals. There are two possible countervailing effects that competition could have on trust within organizations. Firstly, a highly competitive environment might encourage managers to cut any costs possible. This could mean, for example, that competition might induce a manager to renege on promised bonus payments to employees, even if this comes at the expense of trust. This logic would suggest a negative relationship between competition and trust inside organizations. On the other hand, a competitive product market might require that a firm be as productive as possible, and this could include accessing organizational structures and ways of doing things inside a firm that rely on informal agreements. For instance, a monopolist might get away with not being as productive as it could be if there are no competitors waiting in the wings. In this way, a lack of competition breeds indolence, which could extend to laziness about building trust with employees. As argued above, informal agreements can boost productivity, and this could be a distinct advantage in a competitive environment. A competitive firm might have a significant gain (in market share for example) if it can become even slightly better than its rivals. Competition, by this logic, creates incentives for management to be trustworthy. In fact, the empirical evidence from a 2022 study suggests that this second effect is dominant; firms facing a competitive product market have higher levels of employee trust [8].

Market downturns can cause trust to be broken

One potential cause of a breakdown in trust is a market downturn. If a firm suffers a negative shock, it might be difficult for management to keep their past promises; the short-term temptation to renege could be too great. A firm might fear that it will not survive without the short-term boost provided by reneging on an agreement, like the immediate cost saving from not paying bonuses. All firms are going to face a downturn or challenges at some time, meaning that managers will sooner or later have an incentive to break their promises. Sometimes they will succumb, as the benefits from breaking an employee's trust will be too large relative to the future anticipated costs. While managers might have made promises in good faith, circumstances change and external shocks might make keeping those promises no longer feasible (or, more correctly, a self-interested manager may find it in their interests to renege). Covid-19, and the resulting downturn in many sectors, is one example of a shock that could cause management to reevaluate their previous commitments. As noted above, once broken, trust is difficult to rebuild [9].

Consequently, despite the potential to invest in a pro-trust organizational culture, long-lived firms will often find it difficult to maintain employee trust and access to informal agreements in the long term [8]. When there is a recession in the economy, all firms potentially face this risk of a breakdown in trust. When promises are broken in lean times, it might not be possible to revert to the trust-based way of organizing the firm when good times return, hurting profit in the long term. This is also a case where a good manager might be able to effectively communicate with employees that circumstances have changed, and that a new informal arrangement is now required, at least temporarily. This requires both mutual trust between managers and employees and a way that managers can credibly commit to the new arrangement in the future; effective communication begets trust, and vice versa. As the authors of a 2017 study note, however, this is difficult [9].

This is also an issue for firms in declining sectors. As immediate survival in a shrinking market becomes paramount, managers might forgo the possibility of future productive relations with their employees in order to capture some temporary advantage to ensure the firm's immediate survival. As a consequence, trust could be broken in an environment where a firm needs it the most to help ensure its survival; breaking trust might help a firm win the battle but lose the war.

As outlined above, there could be similar incentives if there is an increase in product-market competition; management in some firms may opt to renege on promises to realize a short-term gain at the expense of a more productive cooperative (trust-based) outcome in the long term.

Negative shocks mean that trust is lost, not earned

An issue with incomplete contracts is that, given their informality, they need to be self-enforcing. As the costs and benefits of adhering (or reneging) on previous deals change, an incomplete contract can become non-enforceable. When management (or employees for that matter) renege, trust is broken. Given it is more likely in a longer employment relationship that a significant negative shock will occur, trust in organizations tends to erode over time.

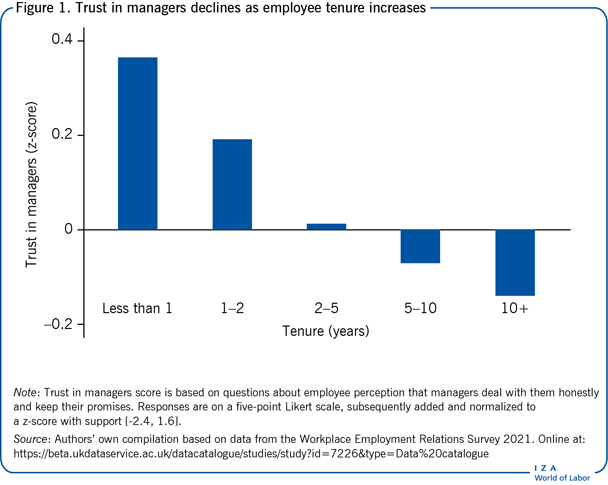

Despite common misconceptions that trust is earnt, empirical evidence suggests that managers lose the trust of their employees the longer the relationship [1] or the older the establishment [8]. Most people commence a new workplace relationship with some propensity to trust the other party, though the degree to which they trust will no doubt be partially determined by the social norms of their background. This stock of trust, however, can be eroded through the actions of others, such as breaking promises or not fulfilling what would be expected according to the informal agreement. This means that employee trust of management at their workplace tends to decrease the longer they work there. This is evident in the study from 2020, whose authors found that average employee trust of management declines with employee tenure; that is, trust falls as the duration of an employee–firm relationship increases [1]. This negative relationship between employee trust of managers and their tenure is also illustrated for the UK in Figure 1.

This suggests that a long-term relationship between an employee and a firm's management is a double-edged sword. The potential for a long-term relationship between an employee and a manger can help induce trustworthy behavior, as it provides a way of rewarding and punishing good and bad behavior. A longer relationship, however, means that there will be more occasions on which one party or the other will act dishonestly, thereby breaking the informal agreement and causing trust to erode.

Labor mobility makes trust more difficult

Long-term relationships, with the possibility of future punishments and rewards, can create a situation in which both employees and managers choose not to exploit their short-term selfish opportunities. Rather, they both might have an incentive to adhere to an informal (long-term) agreement. Trust in this sense relies on an ongoing workplace relationship. In the modern labor market, however, more people increasingly face frequent job changes; there is evidence of a downward trend in average tenure and an increasing reliance on temporary employment contracts. While in the past it was not uncommon for a person to spend their entire career at one organization, this is increasingly rare. Shorter tenures, often of even less than a year, have become more common.

Labor mobility has implications for trust in organizations. Specifically, shorter employment relationships reduce the reputational costs to managers from breaking their word. This is problematic, as in knowledge-based industries the know-how of employees is vital for good decision-making. Moreover, modern markets, with increased globalization, are increasingly competitive. Both trends suggest that trust, and the ability to access informal agreements that facilitate delegation, are increasingly important.

Trust is difficult to manage because it is the combination of social norms, managerial practices, and individual relationships

An advantage of trust is that it allows management to delegate more decisions to employees than without it, making better use of employees’ skills and knowledge. But better managers will most likely be able to both elicit more trust from their subordinates and manage more delegated projects. More generally, good management practices complement one another, and these different aspects of best practice are typically implemented as a package, not as an à la carte selection from a menu. This means that fostering trust is not something that a manager can do in isolation from other managerial practices in a firm; trust will complement other choices about the work environment, including formal incentive contracts.

If labor mobility limits a manager's ability to rely on long-term relationships to enforce trust, they will have to fall back on social norms or other means to demonstrate trustworthiness and elicit trust. As noted, individual relationships between a manager and an employee are important, as is the overall culture of a business. A trusting workplace culture can be fostered by the suite of managerial practices a firm adopts, such as decentralization of decision-making authority, use of teams, flexible job assignments, setting of targets and use of incentives. Importantly, each practice should not be considered as a separate activity in isolation, but rather as part of a bundle of complementary managerial practices that contribute to a firm's overall productivity [6], [10], [11].

Trust cannot overcome all issues faced in an organization, of course. One potential difficulty that arises with incomplete contracts is that evaluations depend on a manager's subjectivity. While this makes trust more important, it also means that these evaluations are subject to the manager's biases (which could be subconscious), and these do not necessarily disappear with trust.

Limitations and gaps

Empirical studies show that seemingly similar firms in terms of their industries and firm characteristics (labor and capital inputs, physical technologies, and so on) can have markedly different outcomes in terms of productivity. A study from 2013 suggests these differences in performance are because some firms can access productive informal agreements, whereas others cannot [12]. Notwithstanding the difficulty of determining the causal link between trust and higher productivity, this suggests trust inside organizations is vitally important.

The idea that similar firms can have markedly different outcomes is supported by economic theory—a firm might find itself trapped in a poor situation, with low trust between management and its employees, whereas an otherwise similar firm might enjoy high trust and cooperation, resulting in better outcomes. That is, economic theory suggests that a trust-based outcome is possible, but so is the outcome in which neither management nor employees trust each other. What is missing from economic analysis at this stage is the practical lessons for management on how to transition from the poor state-of-affairs to the good one.

What economic theory does suggest is that the transition can be difficult, even if it is in everyone's best interests to get out of a low-trust environment to one based on mutual trust. Often it is just not worth it for either a manager or an employee to “go it alone” and start trying to trust when the other person does not trust them. This means that both the manager and the employee need to shift to trusting each other together—but that is difficult, and the empirical evidence suggests that once broken, trust is difficult and slow to rebuild.

Summary and policy advice

There are several practical implications for practitioners of this research. Firstly, trust in organizations has real value. This means that managers need to do their best to promote trust and make themselves trustworthy. Good managers elicit trust through consistent and unbiased decisions and through clear and effective communication. Managers should know that trustworthiness is built on “telling things the way they are,” rather than glossing over issues or through obfuscation; news need not always be good from management. Secondly, as firms become more productive, so does the overall economy. This suggests that governments might be able to facilitate better-run firms through management training programs, much like a modernized version of the state-sponsored training programs in the US of yesteryear [13].

Thirdly, policymakers should also be aware of the potential benefits of competition in facilitating trust in organizations, and the benefits that come with it. Competition (or anti-trust) authorities in most countries have emphasized the product-market benefits of greater competition (less collusion), such as lower prices for consumers. Research suggests that in addition to these benefits of avoiding firms (tacitly) colluding, competition spurs firms to be better managed. As part of this, it seems managers in firms are encouraged to try to develop trust between themselves and their employees to access more productive working arrangements.

Finally, while trust between management and workers is valuable in any organization, this is particularly true for firms in knowledge-based industries when complex work means that contracts will be incomplete in many crucial ways. As knowledge-based firms constitute an increasing proportion of modern economies, it is these firms that will drive productivity growth and higher standards of living. Furthermore, trust in firms is becoming increasingly important with the shift to remote work, again notably for knowledge workers in the services sectors. Remote work furthers the need to delegate responsibility to subordinates and reduces the possibility of real-time monitoring. A successful modern manager must be able to delegate with confidence that employees will do what needs to be done and employees, for their part, must be confident that managers will follow through on their promises. In this way, developing and maintaining trust may well be one of the most crucial roles of managers this century.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work by the authors contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [8], [10].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Kieron Meagher and Andrew Wait