Elevator pitch

Economists have long recognized that free trade has the potential to raise countries’ living standards. But what applies to a country as a whole need not apply to all its citizens. Workers displaced by trade cannot change jobs costlessly, and by reshaping skill demands, trade integration is likely to be permanently harmful to some workers and permanently beneficial to others. The “China Shock”—denoting China’s rapid market integration in the 1990s and its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001—has given new, unwelcome empirical relevance to these theoretical insights.

Key findings

Pros

Trade among consenting nations raises GDP in all of them.

The benefits from trade tend to be small at the individual level but broadly distributed and hence large in aggregate.

Because trade grows the national pie, it creates an opportunity for every citizen to acquire a modestly larger slice; no one necessarily need have a smaller slice.

Policymakers have multiple levers available to ensure that the gains from trade are more broadly shared.

Cons

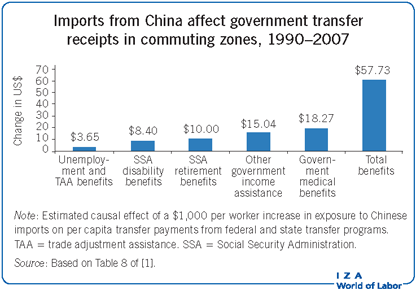

Without policy intervention, trade will almost necessarily harm some individuals and industries.

Labor market adjustments to trade operate with weakness and are materially offset by forces that amplify trade-induced displacement.

The adverse impacts of trade are highly concentrated among specific worker groups and locations.

Trade-induced employment impacts are magnified by inter-industry linkages, creating adverse spillovers to other manufacturers and non-manufacturers.

Trade adjustment programs are too small to be economically consequential, and passive responses to worker displacement impede labor market adjustment.