Elevator pitch

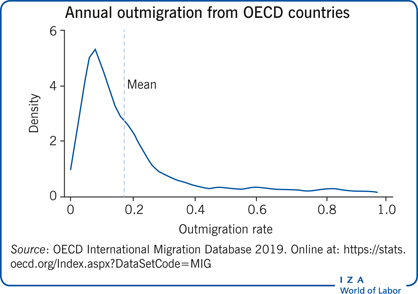

Many migrants do not stay in their host countries permanently. On average, 15% of migrants leave their host country in a given year, many of whom will return to their home countries. Temporary migration benefits sending countries through remittances, investment, and skills accumulation. Receiving countries benefit via increases in their prime-working age populations while facing fewer social security obligations. These fiscal benefits must be balanced against lower incentives to integrate and invest in host country specific skills for temporary migrants.

Key findings

Pros

Temporary migration can fill skills shortages, and migrants’ lower reservation wages imply gains for complementary input factors or firm profits.

Temporary migrants spend their most productive years in the host country, leading to a positive net fiscal impact.

Many returnees invest savings in businesses in their home countries; they may also earn more than non-migrants thanks to skills gained abroad.

Remittances are higher for temporary migrants, raising consumption and investment in their home countries.

Cons

Migrants who intend to stay only temporarily invest less in language skills than permanent migrants.

Lower language skills make migrants less productive than they could be, flatten their earnings profiles, and lower income tax contributions.

Higher remittances imply lower demand for local goods and services and lower consumption taxes paid in the host country.

Emigrants spend their most productive years abroad yet may rely on their home country’s social security system for retirement.