Elevator pitch

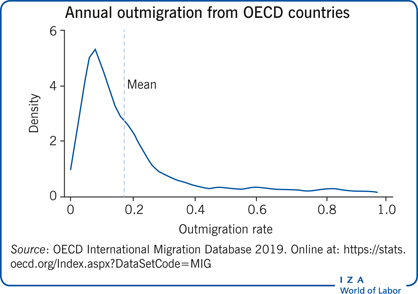

Many migrants do not stay in their host countries permanently. On average, 15% of migrants leave their host country in a given year, many of whom will return to their home countries. Temporary migration benefits sending countries through remittances, investment, and skills accumulation. Receiving countries benefit via increases in their prime-working age populations while facing fewer social security obligations. These fiscal benefits must be balanced against lower incentives to integrate and invest in host country specific skills for temporary migrants.

Key findings

Pros

Temporary migration can fill skills shortages, and migrants’ lower reservation wages imply gains for complementary input factors or firm profits.

Temporary migrants spend their most productive years in the host country, leading to a positive net fiscal impact.

Many returnees invest savings in businesses in their home countries; they may also earn more than non-migrants thanks to skills gained abroad.

Remittances are higher for temporary migrants, raising consumption and investment in their home countries.

Cons

Migrants who intend to stay only temporarily invest less in language skills than permanent migrants.

Lower language skills make migrants less productive than they could be, flatten their earnings profiles, and lower income tax contributions.

Higher remittances imply lower demand for local goods and services and lower consumption taxes paid in the host country.

Emigrants spend their most productive years abroad yet may rely on their home country’s social security system for retirement.

Author's main message

Migrants who plan to return to their home countries save more, send higher remittances, and accept lower-paid job offers. They also have a lower incentive to integrate and invest in host country specific skills, which hinders their careers. These micro-level choices have macroeconomic implications in both sending and receiving countries, from remittances and entrepreneurial investments in migrants’ home countries to fiscal contributions in immigration countries. Receiving countries face a trade-off: while return migration before retirement limits the cost to public benefit systems, prospects to settle permanently improve careers and integration, thereby increasing tax revenue, and strengthening social cohesion.

Motivation

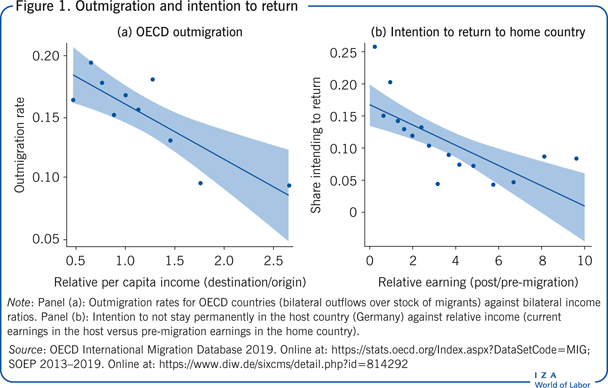

Many, if not most, international migrants do not plan to stay abroad permanently. Outflows from OECD countries hover around 60% of the level of inflows. Panel (a) of Figure 1 shows yearly outmigration rates in the OECD for 2019, which average at 15%. Many of the migrants leaving their host country will return to their country of origin, while some may move on to third countries. In line with the idea that income differentials are a driver of migration, outmigration rates decrease with larger income differentials between receiving and sending countries: when immigrants’ host countries are rich relative to their country of origin, immigrants are less likely to leave in a given year. A similar pattern can be observed in micro-level data: the German Socio-Economic Panel records immigrants’ current and pre-migration earnings, together with their intention to return. Panel (b) shows a strong negative relation between immigrants’ earnings gains from migration and their intention to return.

The share of temporary migrants among all migrants varies greatly across countries. While countries with a long history of immigration such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US have relatively low outmigration rates, numbers are substantially higher in Europe. In countries of the Persian Gulf, which host many migrant workers, migration is almost exclusively temporary since visas are generally tied to work contracts.

In addition to the scale of return migration, its effects depend on the composition and the motivation of returning migrants. There is some evidence of negative selective outmigration, that is, those in lower-paid occupations leaving earlier. Yet, migrants return to their home countries for a variety of reasons: a preference for consumption in the home country (especially during retirement), family-related reasons, a relatively higher purchasing power of the host country currency in the home country, and time limits on their right to stay in the host country.

So, why should researchers and policymakers care about return migration and the duration of migration spells? Migration duration on the one hand and economic choices and outcomes of migrants on the other are interdependent. These choices matter not only for migrants’ own careers and well-being, but they also have consequences for non-migrants in both sending and receiving countries. Such spillovers to the non-migrant population in either country mean that understanding the determinants and implications of migrants’ length of stay is highly relevant to policymakers.

This article focuses on the consequences of temporary migration. Yet, temporariness itself is often a choice that is made in conjunction with other decisions and depends on the economic opportunities in both the host and home countries. Research on temporary migration had long been held back by a paucity of data as governments record outmigration in much less detail than immigration. In recent years, however, drawing on better data, a number of studies have generated valuable insights, allowing for a more thorough analysis of the topic.

Discussion of pros and cons

Receiving countries

Integration

Migrants who expect to stay longer in a host country have a stronger incentive to integrate into that country's society, to acquire host country specific human capital such as language skills, and to build a professional network. These assets affect career progression, productivity, and earnings in the host country, but are potentially less valued in the country of origin. Migrants with return intentions may thus find it optimal to forgo such host country specific investments when integration and skill acquisition is costly.

Beyond their effects on immigrants themselves, human capital investments that depend on migrants’ return intentions also affect the next generation: for example, sons of migrant fathers who plan to stay in Germany permanently have been shown to be more likely to complete upper secondary school. In fact, country-specific investments go beyond education or language: immigrants who plan to stay permanently invest more in broader host country specific human capital that may further both immigrants’ careers and their attachment to the host country [1].

Evidence of higher investment in education, and of higher wages, has been documented in studies that compare outcomes for refugees, who are assumed more likely to stay longer-term in a host country than economic migrants, to those of non-refugees. A stark piece of evidence on the economic benefits of integration comes from a study that exploits a reform-induced quasi-exogenous variation in the waiting time for citizenship applications to show that naturalized immigrants receive a career boost from better integration by investing more in language skills and vocational training. In addition to better language skills, immigrant women who face shorter waiting times before they can apply for citizenship are more likely to work, work full-time, and hold their jobs for longer [2]. Such integration into the labor market supports social cohesion, which may make immigration a less politically controversial topic.

Labor supply

Besides the incentive to accumulate host country specific human capital, a longer-term stay assimilates immigrants’ labor supply behavior to that of natives, whose reservation wage—the minimum wage that the worker requires in order to participate in the labor market—typically is higher. Since most temporary migrants leave their home country for work, this is an important margin.

Migrants who leave their home countries with the aim of accumulating assets, part of which will be spent after return, more often migrate without dependent family members and value leisure in the host country less. Their reservation wages are thus lower than those of permanent immigrants or comparable natives [3]. Possible negative effects of immigrant workers undercutting the wages of natives may partly be mitigated by better integration of longer-term migrants.

Immigration systems in some countries explicitly target low-paid immigrants to provide labor for specific sectors avoided by natives. In many countries in the Persian Gulf, migrant workers are an integral part of the economy: since many natives prefer public sector jobs, foreign contract workers make up most of the private sector labor force. In Western Europe and the US, agricultural harvesting is often performed by temporary workers at wages many natives are unwilling to accept. Given the low number of working-age individuals per retiree in many high-income countries, the benefits of immigration extend to an increase in the working-age population. Particularly, temporary migration can help mitigate the increasing burden on pension systems, counteracting demographic trends that threaten many countries’ fiscal sustainability.

Saving

Whereas better integration and lower labor supply of longer-term immigrants comes at little or no cost to migrant sending countries, a choice that has received more attention in economic migration research is the decision of how much to save and possibly remit. Evidence points toward lower savings and remittances by permanent migrants [4]. While this benefits local demand for goods and services in receiving countries, it comes at the expense of consumption and investment in migrants’ countries of origin. In contrast, temporary migrants remit a larger share of their savings instead of consuming or investing them locally in the receiving country.

Fiscal contributions

The fiscal contributions of temporary immigrants relative to permanent ones are theoretically ambiguous. On the one hand, permanent migration leads to better integration and labor market outcomes, whereas temporary migrants have flatter earnings profiles, resulting in lower income tax payments. Moreover, compared to permanent migrants, temporary migrants save and remit more as consumption is deferred to the country of origin, implying lower payments of indirect taxes such as VAT.

On the other hand, this must be contrasted with temporary migrants’ higher labor supply and limited access to the host country's welfare system. Temporary migrants often spend their most productive and healthy years in the host country and return to their country of origin for retirement, when high health and fiscal expenses are incurred. A model calibrated to the Swedish economy (including its high tax rate and strong welfare state) predicts large fiscal net contributions over their lifetime by individuals aged 20 to 30 on arrival, and net losses for immigrants above the age of 50 [5]. Many temporary migrants leave their host country around retirement age. This implies potentially large gains for countries hosting working-age migrants: in the OECD, social spending on adults above the age of 65 is almost six times as high as that on the working-age population.

The fiscal contributions of immigrants also depend on the type and specific characteristics of migrants deciding to stay longer-term. Empirical evidence points toward an overall negative selection of returnees from the population of immigrants, suggesting that those who remain permanently are the more productive ones. A study on Germany that endogenizes return migration and savings choices estimates the impact of pension and unemployment insurance systems [6]. It finds that the fiscal gains from temporary migration are higher than estimated in models that assume return migration decisions to be exogenous, precisely because of the negative selection of return migrants.

In sum, receiving country governments must trade off the advantages of temporary and permanent immigration. One of the important take-aways is that migrants’ behavior in the host country and economic outcomes crucially depend on whether their stay is anticipated to be temporary or permanent.

Sending countries

Remittances

A key benefit for migrant sending countries is capital repatriation through savings and remittances by emigrants. Remittances from the diaspora make up a large share of financial inflows to many countries. Unlike foreign capital investments, remittances tend to be countercyclical. The scale of both repatriated savings and remittances has been shown to be markedly higher for temporary compared to permanent migrants. Motives for sending money home range from supporting consumption of family members left behind to savings and investments for the time after the return to the home country. Remittances are higher when close family members remain in the country of origin, as often is the case for temporary migrants. A further motive for such remittances is that they serve as a form of insurance, preserving networks and goodwill for after the migrant's return. All these motivations are stronger for migrants expecting to return.

Remittances are an important way to overcome credit constraints in many low-income countries and facilitate, for instance, the education of young family members. Remittances are also an important source of national income, with macroeconomic implications for both inter- and intra-national inequality.

Despite having decreased over time due to new technologies such as mobile money, remittance fees and losses incurred due to below-market exchange rates frequently still exceed 10–15% of the sending value, especially for relatively small amounts. Given the large aggregate volume of remittance flows, lowering this cost would greatly enhance efficiency.

Entrepreneurial investment by returning migrants

In lower- and middle-income countries, self-employment and entrepreneurship are frequent paths out of poorly paid wage employment. For many migrants, temporarily working abroad is a mechanism to accumulate the capital needed to start a business in their home country, where they may face tight credit constraints. In the absence of collateral, bank loans as seed capital are not available to many would-be entrepreneurs, while temporary migration is.

A high propensity for return migrants to start entrepreneurial activity and a tendency to rely on savings accumulated abroad have been documented in many contexts, including Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia, and Bangladesh. Evidence further suggests that enterprises founded by returning migrants are more likely to survive and create employment opportunities for workers beyond the migrants themselves.

Employment upon return to the home country

In many countries, individuals who have been abroad are better educated than non-migrants. Yet causal estimates of the impact of migration experience on labor market outcomes upon return are inconclusive and context dependent. The core challenge is to account for selection into both emigration and return migration. Frequently, emigrants are positively selected from the population in their country of origin, whereas return migrants are negatively selected from the population of migrants, a pattern that has been documented for multiple countries. One example of positive outcomes for returnees is seen in Egypt, where returning migrants have been shown to enjoy a wage premium compared to non-migrants.

Migrants who return to Mexico also earn on average higher wages than non-migrants. Yet, this wage effect appears independent of migration duration, suggesting that migrants do not accumulate skills that are valued at home. Instead, observed wage differentials may be driven by a positive selection of migrants from the sending country's population. Taken together, these insights suggest that the effect of return migration on labor market outcomes in the country of origin depends crucially on context and how experience in host countries is rewarded in the home labor market—if it is valued there, return migrants will likely command a wage premium relative to those who never migrated.

Broader effects of temporary migration on well-being in the sending country

Migration of a household member can raise the remaining family's income and consumption through remittances. However, there are also more indirect channels through which non-migrants are affected; for example, women in families of migrating men are more involved in household decision-making [7]. On the other hand, remittances by temporary migrants may decrease the labor supply of other family members. In addition, the reduced labor supply in local labor markets with many emigrants may raise the wage rate for adults and reduce the need for child labor, as households previously relying on child labor in addition to adults’ earnings may be able to get by only on adults’ (now higher) earnings. Yet, at the same time, the absence of a caregiver and a potentially greater burden of household chores on children may negatively affect their education.

Return migrants can also affect social norms in their home countries. In families of returnees to Jordan from relatively more conservative countries in the Persian Gulf, women have been found to enjoy fewer freedoms [8]. This also extends to adopting the fertility preferences of host countries: return migrants to Egypt who temporarily lived in higher-fertility countries of the Middle East have more children than non-migrants [9]. Fertility assimilation also occurs the other way round, with migrants to low-fertility countries such as Germany adjusting downward their completed fertility relative to the average in their home countries.

Linking sending and receiving countries

Brain circulation

The emigration of highly skilled workers is frequently referred to as “brain drain.” Yet, migration may equally lead to a “brain gain” for the home country. The reasons are twofold: first, the fact that in many destination countries the opportunity to obtain a visa and job offer increases with an applicant's education level creates incentives for educational investments prior to migration, with some of these better-educated individuals ultimately never migrating. Second, the return of migrants, who may have acquired productive skills while abroad or formed valuable networks, may well leave an overall positive effect on a migrant sending country's human capital stock. A prime example for the latter is student migrations: international students go abroad to accumulate skills that are valued in their home country's labor market.

Skill accumulation may also occur “on the job,” that is, for migrants who go abroad to work rather than to study. Again, for the case of Egypt, returnees have been found to experience greater occupational mobility upon return than non-migrants, especially the better-educated. Crucially, the effect is increasing in migration duration, suggesting skill acquisition abroad [10].

Migration promotes innovation: knowledge diffuses faster when skilled workers migrate, as shown by the example of researchers who patent more innovations following migration, with positive spillovers on the patenting of their non-migrant collaborators in the country of origin. The return of skilled migrants, and the transfer of knowledge and technology they bring with them, can also contribute to industrial development in their country of origin through improved export performance, and even help reconstruction in post-conflict situations [11]. Ultimately, the benefit of brain circulation for sending countries depends on the propensity of high-skilled migrants to return.

Migration to mitigate asymmetric shocks in a currency union

Migration inherently links economic outcomes across countries and can even affect countries at similar stages of economic development. One prominent example is that of countries sharing a currency but facing idiosyncratic shocks. In currency unions, exchange rates cannot adjust to help cushion shocks to a specific country's productivity or the demand for its output. In the absence of integrated fiscal policy, an alternative margin of adjustment in response to shocks that affect countries differentially is labor mobility. Temporary migration can attenuate wage and employment effects in countries experiencing negative shocks. A prime example is the Eurozone, a currency union that has left fiscal policy largely unintegrated. In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, southern European countries were disproportionately affected, their economies shrank, and unemployment rose. In response, many working-age individuals moved to northern Europe. Many of these migrations were temporary, with migrants returning as their home countries recovered. The prime reason for temporary work abroad in many of these cases was not asset accumulation, but the avoidance of unemployment spells and the ensuing depreciation of skills.

Empirical evidence supports this: net migration (immigration minus emigration flows) in the EU moves from places with relatively higher unemployment to those with relatively lower unemployment, and the possibility to migrate lowers unemployment and inequality in the Eurozone [12]. Similarly, in a developing country context, migration has been shown to lower inter-regional wage inequality in West Africa [13]. Yet, while migrations in times of economic crises alleviate pressure on social security systems in adversely affected countries, skill-biased migration of well-educated workers may dampen the capacity of labor mobility to dissipate negative shocks: the departure of the most mobile and educated workers may reinforce negative effects on lesser-skilled workers left behind.

Other macroeconomic implications

Migration raises aggregate long-term welfare for both sending and receiving countries, through remittances, productivity increases, and consumption. In addition, migration promotes trade between immigrants’ home and host countries, including after their return home, thanks to a network spanning both countries and knowledge of relative strengths and needs of both economies. Temporary migration is particularly conducive to trade (both to imports and exports), since migrants who plan to return have more to gain from maintaining closer ties with their home country.

Political economy

Clearly specified objectives and correspondingly designed immigration policies may help make immigration a less contentious issue in receiving countries. The example of the US is instructive: while for decades Congress has failed to enact a comprehensive immigration reform, border enforcement and local or state-level immigration legislation have been tightened continuously. The increased difficulty for potential migrants to enter the country, and move back and forth, has contributed to making temporary migration more permanent, risking further erosion of immigration support.

Limitations and gaps

Though improving, data on return migration is still the biggest limiting factor to generating insights into the economic implications of temporary migration. Ideal datasets to study this topic would be panels that track migrants across countries and across time. Accurately registering emigration (and the destination of emigrants) would help too.

Given that there is still only little information on emigration and emigrants’ destinations, studies that analyze return migration frequently make the simplifying assumption that they return home. While this is mostly true (e.g. two-thirds of migrants who leave Sweden return to their country of origin; a yet higher share of temporary migrants in Germany report an intention to specifically return to their country of origin), some migrants also move on to another host country. Such onward migration is still relatively unexplored.

Summary and policy advice

Temporary migration differs from permanent migration in its economic implications for home and host countries. The topic has thus received increasing attention, with research acknowledging the importance of understanding how migrants’ behavior and economic outcomes depend on whether the migration decision is temporary or permanent.

Recent research points to the importance of clarity about the prospect to stay longer term for investing in human capital. This is particularly important for migrants who, if allowed, are likely to stay in the country for an extended period, such as refugees. Enabling optimal investment in human capital can mean providing access to language courses and the labor market, notably by removing employment restrictions. While better integration may help host countries retain high-skilled immigrants, there may be a conflict of interest between origin and destination countries.

Besides the actual return to the country of origin, the anticipation to do so induces migrants to remit and maintain links with their home communities. Brain drain effects through the permanent emigration of highly skilled individuals can be limited by lowering the cost of remittances, and by fostering knowledge exchange and trade links between migrant sending and receiving countries. Finally, well-communicated policy objectives that are benchmarked against cost–benefit analyses of temporary and permanent immigration schemes may improve public sentiment toward immigration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on an earlier draft. Financial support by the Volkswagen Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Joseph-Simon Görlach and Katarina Kuske