Elevator pitch

Workplace sexual harassment is internationally condemned as sex discrimination and a violation of human rights, and more than 140 countries have enacted legislation prohibiting it. Sexual harassment increases absenteeism and turnover and lowers productivity and job satisfaction. Yet, it remains pervasive and underreported, as the #MeToo movement starkly revealed in October 2017. Standard workplace policies such as training and a complaints process have proven inadequate. Initiatives such as bans on confidential settlements and measures that support market incentives for deterrence may offer the most promise.

Key findings

Pros

Largely overlooked until the 1970s, sexual harassment in the workplace is now internationally condemned as a form of sex discrimination and a violation of human rights.

More than 140 countries have legislation prohibiting workplace sexual harassment.

Legislation varies by country and includes protection against workplace sexual harassment under both civil and criminal law.

Like workers at risk of injury or death, those at risk of sexual harassment receive a pay premium.

Bans on confidential settlements show promise by incentivizing firms to deter harassment in order to avoid reputational damage.

Cons

Sexual harassment is difficult to define, measure, and monitor, and estimates of prevalence range widely.

Sexual harassment is costly to its targets and to the organizations in which it occurs.

There is limited empirical evidence on the efficacy of legislative and workplace policies in reducing workplace sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment is underreported, which reduces the efficacy of legislation and workplace policies prohibiting it, as these policies depend on reporting to discourage harassment.

Costs to organizations may be too low for deterrence due to confidential settlements, low caps on damages awards, and insurer coverage of damages awards.

Author's main message

Sexual harassment, a violation of human rights and a form of sex discrimination, is costly to workers and organizations. Yet it remains pervasive and underreported. Legislation and organizational policies have been insufficient to eradicate workplace sexual harassment. Success may require policies to enhance market and legal incentives by raising the costs to organizations of tolerating an adverse work environment. Promising measures include banning confidential settlements so that harassing firms and individuals risk reputational harm, raising caps on damages awards, denial of coverage by insurers of willful illegal acts, and a complaints process that protects workers from retaliation.

Motivation

Before the 1970s, the term “sexual harassment” would have been met with a blank look. Sexual overtures and disparaging remarks about workers’ competence based on their gender were widely considered acceptable behavior. Recognition of sexual harassment as an illegal workplace behavior originated in the US following influential work by Catharine MacKinnon, who argued that sexual harassment is sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1980, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) issued guidelines defining workplace sexual harassment. Many countries quickly followed the US’s lead in recognizing sexual harassment as an illegal form of workplace behavior.

Sexual harassment in the workplace is now internationally condemned as a form of sex discrimination and as a violation of human rights. It is costly to workers and organizations. Organizations have long provided training and complaints processes with the goal of preventing sexual harassment. Yet, as revealed by the #MeToo social movement initiated by Tarana Burke in 2006 gained significant global attention in October 2017, when millions of people around the world shared their experiences of sexual harassment, it remains pervasive and underreported. What institutional failures prevent its eradication, how effective is legislation, and what policies can reduce the incidence?

Discussion of pros and cons

Defining sexual harassment

Sexual harassment includes a wide range of behaviors, from glances and rude jokes, to demeaning comments based on gender stereotypes, to sexual assault and other acts of physical violence. Although the legal definition varies by country, it is understood to refer to unwelcome and unreasonable sex-related conduct. A fairly comprehensive definition as stated by the United Nations (UN) Secretariat (ST/SGB/2008/5, page 1) considers sexual harassment as “any unwelcome sexual advance, request for sexual favor, verbal or physical conduct or gesture of a sexual nature, or any other behavior of a sexual nature that might reasonably be expected or be perceived to cause offense or humiliation to another. Such harassment may be, but is not necessarily, of a form that interferes with work, is made a condition of employment, or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment”.

Acts of sexual violence are always considered to be sexual harassment (as well as criminal acts). Suggestive jokes or insulting remarks directed at one sex may be considered sexual harassment in the legal sense, but not always, depending on context and frequency. And there is not a clear line between annoying courtship overtures and sexual harassment. Quantifying the severity of sexual harassment is even more challenging, as people react differently to objectively identical treatment.

Prevalence and trends

Survey evidence documenting that sexual harassment is widespread has been important to the development of sexual harassment law. But survey methodologies differ widely, and, even among studies with representative samples, estimates of the prevalence of sexual harassment vary considerably.

Surveys use two methods to elicit responses on experiences of sexual harassment: direct query, in which respondents are asked to report whether they have been sexually harassed according to their own perception of what behaviors constitute harassment; and a behavioral experiences survey, which asks respondents to indicate whether they have experienced any of the behaviors on a list identified by the researchers as sexual harassing behavior. Among other questions, respondents to behavioral surveys are typically asked to report whether they have experienced any of the following unwanted or uninvited behaviors within a specified time period: sexual teasing, jokes, remarks, questions; sexual looks, gestures; deliberate touching, leaning, cornering; pressure for dates; letters, calls, sexual materials; stalking; pressure for sexual favors; and actual or attempted rape or assault [2]. A meta-analysis using 55 probability samples (random selection) based on articles published between 1976 and 2000 for the US finds that the reported incidence is about double when based on a behavioral survey (58%) than on direct query (24%) [3].

In addition to differences in reporting methods, surveys differ substantially in time period covered and population surveyed. The time periods requested for reporting sexually harassing behavior vary among studies from as little as three months to any past experience with no time limit. Some surveys are based on national samples, and others are based on convenience samples of workers in specific occupations, industries, or workplaces [3], [4]. The range of prevalence rates reported in the literature is substantial, with one review of the literature reporting that 25% to 85% of US women have experienced workplace sexual harassment [4].

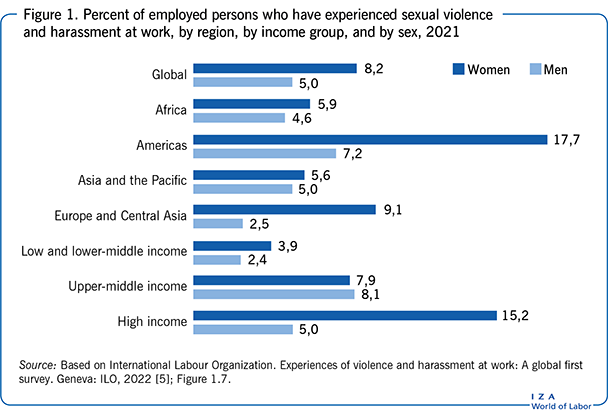

Methodological differences limit the ability to make cross-country comparisons or to identify trends. Using the direct query approach, the ILO-Lloyd’s Register Foundation-Gallup survey was fielded in 2021 on nearly 125,000 individuals in 121 countries and territories [5]. This survey represents the first attempt to provide international evidence on work-related violence and harassment using a consistent methodology across countries. Among other questions, respondents were asked, “Have you, personally, EVER experienced any type of SEXUAL violence and/or harassment AT WORK, such as unwanted sexual touching, comments, pictures, emails, or sexual requests while AT WORK?”. Figure 1 summarizes sexual violence and harassment rates among employed persons by region, by income group of the country, and by sex. Globally, 8.2% of women and 5.0% of men report that they have experienced sexual violence and harassment at work in their working life. Prevalence rates vary by region, with the Americas reporting substantially higher rates than other regions at 17.7% among women and 7.2% among men. Within all regions, women report higher prevalence rates than do men, with the disparity largest in the Americas and Europe and Central Asia. Prevalence rates also differ by country income group. Women in the high-income countries report a prevalence rate of 15.2%, more than three times the corresponding rate of 5% for men. By contrast, both women and men in low and lower-middle income countries report rates under 4%.

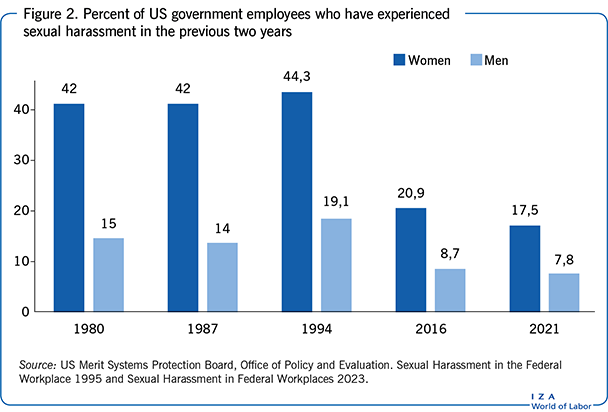

The most reliable trend evidence is from a survey of US government workers conducted using the behavioral experience methodology five times between 1980 and 2021 [2], [6]. Survey respondents reported whether they had experienced any of the described behaviors during the preceding two-year period. As Figure 2 demonstrates, the rate of sexual harassment behaviors did not decline over the 1980 to 1994 period, with rates for women of 42–44% and rates for men of 14–19%. But the 2016 and 2021 surveys show substantially lower rates of 18–21% for women and 8–9% for men.

Who is sexually harassed?

Although both men and women are sexually harassed, international survey data show that a majority of targets are women. Targets are more likely to be younger, hold lower-position jobs, work mostly with and be supervised by members of the opposite sex, and, for female targets, work in male-dominated occupations [2], [7]. Vulnerable populations such as migrant workers are especially subject to sexual assault and other forms of abuse and violence [5].

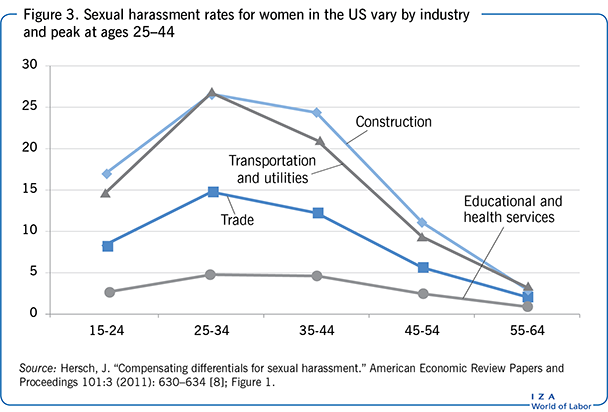

Records of legal charges of sexual harassment provide further information on characteristics of targets. The rate of sexual harassment per 100,000 workers calculated from charges filed with the US EEOC exhibits substantial variation by industry, age, and sex. Women are at far greater risk of sexual harassment than men in every industry and at every age [8]. For both men and women, the risk is highest for those ages 25–44. The sexual harassment rate for women in the female-dominated industries of education and health services is low but about double the rate for men in those industries. The rate for women in the male-dominated mining industry is 71 cases per 100,000 female workers, which is 31 times the male rate [8].

Based on these legal charges filed with the US EEOC, Figure 3 shows the rate of sexual harassment charges per 100,000 female workers by age group for four selected industries. The inverted U-shaped pattern shows a rise in legal charges up to ages 25–44 and a decline thereafter. This pattern also holds for women in other industries and for men in many cases, although the sexual harassment rates for men are uniformly well below those for women [8].

Who are the harassers?

Empirical studies consistently document that a majority of harassers are male and more likely to be at the same or at a higher organizational level than their targets. There is little other evidence of a pattern by social status, occupation, or age, making it difficult to identify likely harassers [9]. Key characteristics include an organization’s tolerance for sexual harassment and the gender composition of the workplace [9], [10]. Sexual harassment is more prevalent in organizations with larger power differentials in the hierarchical structure, and in male-dominated structures like the military [7].

Costs to targets

The productivity and pay of targets of sexual harassment, as well as of their co-workers, are expected to be lower if sexual harassment induces inefficient turnover, increases absenteeism, and generally wastes work time as workers attempt to avoid interactions with harassers. There is extensive evidence of lower job satisfaction, worse psychological and physical health, higher absenteeism, less commitment to the organizations, and a higher likelihood of quitting one’s job [2], [10]. Workers who report sexual harassment are also at risk of retaliation, which results in even lower job satisfaction and worse psychological and health outcomes [7]. Those who report workplace sexual harassment are more likely to leave their jobs [11], [12]; job change following reported sexual harassment in turn leads to greater financial stress for individuals [11] and increased workplace gender segregation and gender wage inequality [12].

Because workplace sexual harassment reduces worker productivity, targets may have lower earnings. But sexual harassment is universally considered an extremely negative working condition, which suggests that a pay premium may arise for this type of working condition, similar to the premiums in jobs in which workers face a high risk of death or injury, risks that are also costly for firms to eliminate. Analysis of sexual harassment charges filed with the US EEOC in 2000-2004 shows that workers are paid a premium for employment in jobs with a higher risk of sexual harassment [8].

Costs to organizations

The adverse consequences for targets of sexual harassment translate into a less productive work environment. The costs to organizations include increased turnover and absenteeism, lower individual and group productivity, loss of managerial time to investigate complaints, and legal expenses, including litigation costs and damages payments to targets [1].

The study of sexual harassment of US government workers estimated the costs of sexual harassment over a two-year period 1992–1994 at $327 million, including job turnover, sick leave, and individual and workgroup productivity, with 61% of the total cost due to reduced workgroup productivity [2]. The reduction in individual and workgroup productivity is estimated to cost organizations an average of $22,500 per person affected by sexual harassment according to a meta-analysis of 41 US studies with nearly 70,000 observations [10]. In fiscal year 2022, the US EEOC resolved 5,664 charges of sexual harassment yielding monetary benefits to the harassed employees of $59 million excluding any benefits obtained through litigation.

Workplace policies

Organizational tolerance of sexual harassment is typically cited as the most important influence on whether sexual harassment occurs in a workplace. But there has been little empirical research on which policies and procedures are effective in creating an organizational climate in which sexual harassment is not tolerated [10].

Because targets are known to be reluctant to report, organizations have adopted “lockboxes” or “information escrows” to provide a confidential process to report complaints. Details vary by organization, but generally targets are given the option of not pursuing a formal complaint unless multiple targets report sexual harassment by the same person. This option lowers the burden to an individual target, who knows that their experiences will be corroborated, and could provide protection against retaliation.

Although empirical evidence on the efficacy of workplace policies in reducing sexual harassment is limited, there is consensus on what policies should be standard in organizations. In addition to training, organizations should emphasize prevention by issuing strong policy statements of no tolerance of sexual harassment and by providing a safe mechanism for complaints of sexual harassment with protections against retaliation. Many workplaces also offer counseling and support to targets. Having a training program and a safe and clear complaints procedure may also protect the organization against legal liability [4].

Legislation

In light of the worldwide publicity generated by the #MeToo movement, international organizations adopted or strengthened conventions and directives specifically addressing workplace sexual harassment. In addition, many countries adopted new laws or strengthened existing laws. A review of legislation applied to the private sector in 192 UN member states as of January 2021 found that 142 countries prohibit sexual harassment at work, with the number of countries prohibiting sexual harassment of both men and women increasing from 121 in 2016 to 134 in 2021 [13]. High-income countries have more protective private sector legislation than low-income countries [13]. This study does not review public sector legislation but notes that it is more protective than private sector legislation in some countries [13].

Depending on the country, sexual harassment may be covered under a range of legal principles: as employment discrimination on the basis of sex, under labor law protections against unfair dismissal, under human rights law, under health and safety laws requiring provision of a safe working environment, under criminal law (especially for sexual assault), as a tort (an intentional act for which courts can grant damages awards), and under contract law (such as breach of contract against unfair dismissal) [14]. Judicial decisions have been instrumental in defining sexually harassing behaviors and in assigning liability and remedies. In the US, sexual harassment is covered under employment discrimination law as a form of discrimination on the basis of sex. The legal tradition in Europe, while also recognizing sexual harassment as employment discrimination, has emphasized the harm caused by sexual harassment to the dignity of men and women at work [14].

The efficacy of such laws depends on the reporting of sexual harassment by targets and others affected by the harassing behavior. Yet sexual harassment is seriously underreported. A review of the literature assessed that only 6% to 13% of employees make a formal complaint based on studies published between 1994 and 2004 [4]. The decision not to report is often justified by concerns about retaliation and the consequent effect on their career and job satisfaction [7].

The threat of legal action can reinforce organizational incentives to eliminate sexually harassing behavior. However, the probability that sexually harassing behavior will lead to a lawsuit is quite low, further reducing the efficacy of laws [8].

Motivated by the #MeToo movement, several US states passed legislation that banned confidential settlements which prevent targets of workplace sexual harassment from speaking publicly about their experiences. The expectation is that the risk of public exposure would act as a deterrent to sexual harassment. Empirical evidence derived from leveraging variation in state legislation suggests that bans on confidential settlements and ensuing public exposure through litigation may be effective as a deterrent [15].

Limitations and gaps

Sexual harassment encompasses a wide range of behaviors and is not easily defined. Survey evidence has been instrumental in raising public awareness about the extent of workplace sexual harassment. The substantial evidence that sexual harassment is frequent and damaging to individuals and workplaces has led to widespread legislation and workplace policies.

The connection between sexual harassment and other forms of workplace harassment, including bullying, warrants further examination. There also is little research that examines intersectional relationships, such as the relationship between sexual harassment and gender identity or sexual orientation. Little is known about the characteristics and motivation of harassers. And although sexual harassment is found to be more likely when organizations tolerate such behavior, there is little specific empirical evidence on what organizational policies or actions are effective in eliminating sexual harassment.

The main puzzle, though, is why sexual harassment in the workplace survives. Because sexual harassment is costly to workers and organizations and is also illegal, there are market and legal incentives to eliminate this behavior. Offsetting these incentives, however, are costs of monitoring and enforcing behavior coupled with low reporting of sexual harassment, which reduce any litigation threat. Thus, tolerance of sexual harassment may be efficient within many workplaces. Research could be productively directed at examining sexual harassment in a broader framework that incorporates market and legal incentives and identifies policy levers that would enhance incentives to comply with laws against sexual harassment.

Summary and policy advice

Sexual harassment reduces individual and group productivity. Yet survey evidence shows that workplace sexual harassment is quite common. It is also substantially underreported, in part because workers are justifiably concerned that reporting may lead to retaliation and an even worse work environment.

Three types of approaches are available to reduce the incidence of workplace sexual harassment: workplace policies, legislation, and market incentives.

First, although empirical evidence is limited, widely accepted best practices include the promulgation of a strong policy prohibiting sexual harassment, workplace training, and a complaints process that protects workers from retaliation.

Second, legislation prohibiting workplace sexual harassment is widespread and increasingly adopted by countries. However, to date, legislation has been inadequate to eliminate it. Enforcement of laws relies on reporting, and underreporting weakens the efficacy of laws. Policies directed at increasing reporting may help support law enforcement and could also reinforce the incentives provided by the market.

The inadequacy of workplace policies and legislation suggests greater focus on the third approach: policies to enhance market incentives to eradicate sexual harassment. Because sexual harassment lowers workplace productivity, and because workers are paid a premium for exposure to the risk of sexual harassment, organizations should respond to these market incentives by striving to eliminate sexual harassment, including through measures such as stronger anti-harassment policies and more effective training programs. However, current market incentives are apparently insufficient to eradicate sexual harassment, indicating that the costs to organizations are too low.

Initiatives that raise the costs to organizations of tolerating an adverse work environment may be effective. Firms that are publicly identified as tolerant of a sexually harassing environment may need to raise the pay premium necessary to attract workers. Bans on confidential settlements as enacted in several US states may deter harassment as firms seek to avoid reputational harm. Many businesses purchase professional liability insurance, which typically provides coverage of even intentional illegal acts such as sexual harassment perpetrated by high level employees. Insurers should cease coverage of illegal employment acts so that firms are financially responsible for harm caused within their firm. Caps on damages awards, currently set in the US as a maximum of $300,000 for the largest firms, should be raised to a level sufficient to provide a financial incentive to curb sexual harassment in order to avoid costly litigation payouts.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Kathryn H. Anderson, Blair Druhan Bullock, and W. Kip Viscusi for helpful discussions. Version 2 of this article updates figures and arguments based on the #MeToo debate and recent developments. It adds new Key references [1], [4], [5], [6], [7], [11], [12], [13], [14], and [15] as well as Additional references.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Joni Hersch