Elevator pitch

Although small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) represent more than 90% of all enterprises and play an important role in employment generation, they lack access to affordable formal finance. Conventionally, market failures and information imperfections are seen as major causes of this misallocation. However, the role of social and political factors in resource allocation, including access to formal finance, has recently become more widely accepted. Firm-level evidence from post-communist economies, for example, shows that political connectedness improves access to bank credit, but is not associated with enterprise growth.

Key findings

Pros

Access to formal finance is skewed against SMEs in favor of large firms.

Market failures and information imperfections do not fully explain why the distribution of formal finance is skewed against smaller enterprises.

Political connections play an important role in gaining access to formal finance.

Evidence shows that formal financing is associated with faster firm growth than informal financing, and that smaller enterprises benefit more from improved access.

Cons

Recent data show that a substantial portion of SMEs in post-communist countries offer bribes to public officials relatively frequently.

Political connectedness exacerbates misallocation of formal finance, often in favor of enterprises with closer links to government officials, which are usually larger and wealthier.

Although political connectedness improves firms’ access to formal finance, most recent country-level case studies find that the practice is not positively associated with firm performance and growth.

Author's main message

Unequal distribution of formal finance between large and small enterprises has traditionally been explained by market failures and information imperfections, prompting policy intervention to increase the flow of bank finance to SMEs. But interpersonal political connectedness exacerbates this misallocation further, often in favor of enterprises with links to government officials. Traditional policy measures should thus be complemented with reforms to improve the transparent and impartial functioning of bureaucratic institutions, whose ultimate goal should be to facilitate, not hinder, market-based exchanges.

Motivation

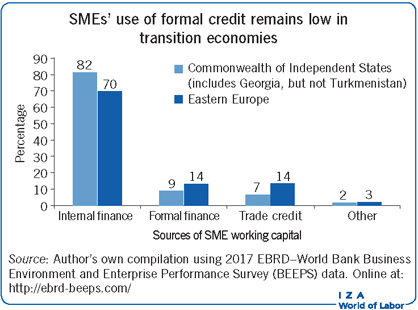

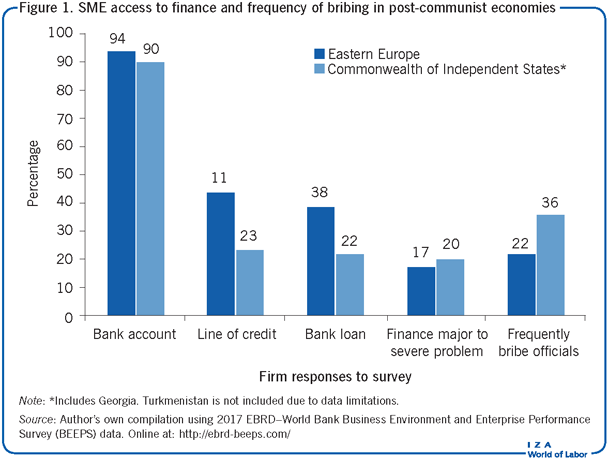

Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play an important role in market economies in terms of employment generation and poverty reduction, as they often operate in labor-intensive stages of the production chain. Most SMEs, however, do not grow beyond their minimum efficient scale due to various external factors, including a lack of access to adequately priced external finance. The situation is made worse by the persistency of corrupt practices linked to bureaucratic institutions. Among all sources of external finance, SMEs generally rely most heavily on bank credit in both advanced and emerging economies. Yet according to firm-level data for 2012–2014 (see the Illustration), SMEs in post-communist economies remain heavily dependent on internal finance, and the share of financing available from banks is only comparable to that offered by suppliers, i.e. trade credit. In addition, although most SMEs have bank accounts and around 40% in Eastern Europe and 20% in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) report having access to formal finance, about one-fifth of SMEs complain that a lack of external finance is a major-to-very-severe problem for their operation and growth (Figure 1). Further, 22% of SMEs in Eastern Europe and 36% in the CIS report having offered bribes or gifts to public officials.

Discussion of pros and cons

Enterprise finance in transition economies: A background

Although more than 25 years have passed since the start of market-oriented reforms in the post-communist economies of Eastern Europe and the CIS, some of the ongoing problems regarding enterprise access to formal finance can be traced to the central planning and transitional reform periods. While the focus here is on Eastern Europe and the CIS, conclusions can easily be extended to other large transition economies, such as China and Vietnam.

At the start of their transformations toward market-based economic systems in the late 1980s,post-communist economies had relatively similar conditions, especially in relation to their monetary systems, banking structures, and enterprise finances. For example, under central planning currency couldonly be used for specific purposes as determined by authorities (unlike in capitalist societies, where currency is a generally accepted universal title for all tradable goods and services). Extra cash holdings of profitable enterprisesdid not, therefore, have independent purchasing power. This created strong incentives for enterprise managers to establish interpersonal relationships with public officials, who, by default, were affiliated with the communist party, to gain access to important scarce resources. As will be discussed later, the impact of interpersonal political connections on resource allocation only grew stronger in the post-transition period.

In terms of finance, the monobank system, which combined commercial and central banking, financed around 50% of enterprise working capital, while long-term fixed capital investments were funded by non-repayable government grants [1]. This phenomenon, also known as “soft budget constraints,” was one of the main criticisms of central planning, as it allowed loss-making enterprises to stay afloat. Reducing enterprise over-dependence on bank finance was thus one of the key policy challenges in the early years of transition. This was meant to be achieved by dividing the monobank system into a market-based, two-tiered banking system consisting of a central bank and commercial banks. As in successful market economies, the central bank would provide effective prudential regulation and supervision of commercial banks, which, in turn, would impose financial discipline on enterprises, thereby ensuring a more efficient allocation of resources.

In reality, however, persistent inflation and the associated macroeconomic instability in the early 1990s adversely affected the general public’s trust in the banking system and, subsequently, the banks’ ability to intermediate between savers and borrowers. More importantly, because inflation eroded the real value of business deposits and simultaneously increased the nominal value of payments under contractual obligations, it ended up making enterprises more dependent upon external finance, thus putting strain on inter-enterprise payments. As a consequence, the sudden and sharp reduction in bank credit (partly the direct outcome of purposeful policies designed to “harden” the soft budget constraints) resulted in enterprises resorting to alternative means of financing their working capital. Bartering, transactions in promissory notes, inter-enterprise arrears, and mutual debt write-offs were observed in almost all transition economies in the late 1990s, but were most severe in Russia and Ukraine where, at its peak in 1998, barter accounted for more than 50% of all industrial transactions [1].

Foreign ownership of banks was also viewed as instrumental in bank restructuring, and was highly encouraged by policy advisors. It was expected that foreign banks would bring market expertise and efficient corporate governance, boost competition and improve efficiency in the financial services industry, and ultimately increase the supply of loans to the enterprise sector, including to SMEs. Contrary to expectations, however, foreign banks were more actively involved in lending to households, which requires relatively less sophistication and expertise compared to lending to businesses [1].

Hence, enterprises in post-communist economies faced severe credit shortages in the 1990s, and the foreign-currency-fueled credit boom of the 2000s also eluded them. As a result, a large proportion of SMEs in post-communist countries remain credit constrained,holding implications for their future operation and growth.

The distribution of formal finance is skewed against SMEs

While acknowledging the size and significance of SMEs in market economies, it is also important to note that SMEs do not have growth aspirations by default, as somemay be set up simply to avoid unemployment.This means that the number of them fluctuates with business cycles [2]. Nevertheless, a large proportion of SMEs are aspirational in the sense that they are established to pursue profitable opportunities and to grow in size; these are known as transformational SMEs. Although a small number of innovative, high-growth SMEs create most of the new jobs, a majority of transformational SMEs do not reach their optimum size due to various external constraints, including inadequate access to formal finance.

Access to adequately priced formal finance is of paramount importance to SMEs’ smooth operation and growth. Enterprise complaints about poor financial access are higher in emerging economies, where almost one-third of enterprises cite a lack of external finance as either the main or a severe obstacle to their operation. Bank financing of SME activities remains low in transition economies too. According to the most recent enterprise survey results (as shown in the Illustration), SMEs were able to finance only 9% of their working capital needs in the CIS and 14% in Eastern Europe through bank loans, which is low compared to the pre-transition figure of 50%.

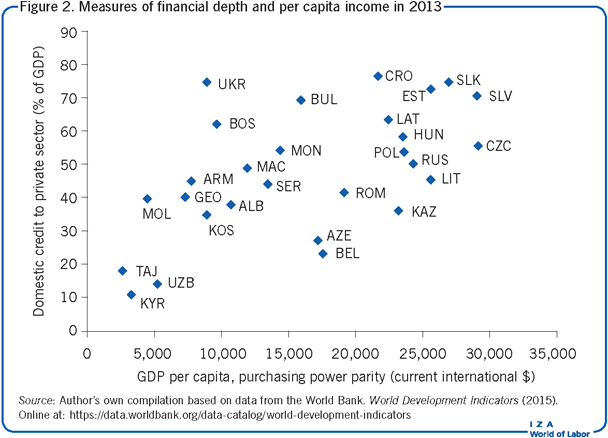

As Figure 2 shows, most CIS countries are less financiallydeveloped and have lower per capita income levels than their Eastern European counterparts, which may partly explain the observed difference in access to finance between the two regions. An important caveat, however, is that these aggregate indicators are rather broad and do not fully reflect the more specific institutional and financial constraints the SME sector faces. For example, although there is rich evidence for a strong positive correlation between financial development and economic growth, this does not necessarily imply causation. While more developed financial systems generally offer better access to financial services, aggregate measures of financial development (such as private sector credits, broad money, banking sector assets, etc.) do not provide enough information about the breadth and quality of financial depth.Moreover, they neglect certain things, such as the proportion of SMEs responsible for the utilization of available formal finance [2].

Of all available sources of external finance, SMEs depend most heavily on bank loans. Moreover, evidence suggests that financing from formal, rather than informal, financial institutions is associated with faster firm growth, and that smaller enterprises benefit more from the improved availability of bank finance [2]. In principle, banks should finance all projects with positive net present value, independent of firm size. But, in practice, the distribution of formal finance is skewed against SMEs, which must also pay higher costs on loans.

The classical explanation of the unequal distribution of finance, which provides a strong rationale for policy intervention in credit markets, highlights market failures as the main underlying cause of misallocation [3]. Market failures occur as a result of information imperfections, which arise for a number of reasons. For example, SMEs are usually younger and less likely to possess acceptable collateral. They are informationally more opaque and face stiffer competition in product markets, which, in turn, affects the predictability of cash flow forecasting. Because SMEs are not scaled down versions of large enterprises, lending to them is seen by banks as high risk. This, the argument goes, explains the lower supply and higher cost of bank lending to SMEs [4].

Political connectedness matters in the allocation of formal finance

An emerging body of literature that draws on institutional economics highlights the role of interpersonal social and political factors in explaining the asymmetric distribution of formal finance across enterprises of varying size [5], [6], [7]. According to this view, entrepreneurial decisions concerning investment, production, and exchange will respond not only to market prices, but also to rules and regulations that can jointly shape incentivizing and hindering mechanisms such as permits, fiscal concessions, and preferential access to resources. Exchanges taking place through anonymous markets are the most desirable;however, the efficiency of resource allocation (including that of formal finance) is largely dependent upon the credibility and effectiveness of bureaucratic organizations, which facilitate the process of exchange, production, and investment by enforcing rules, regulations, and contracts [8].

Bureaucratic institutions in underdeveloped markets usually lack credibility, which causes inefficiencies by hindering market-based incentivizing and constraining mechanisms. Consequently, the role of bureaucratic institutions is partly replaced by community-ruled horizontal webs of interpersonal networks,which can grow in importance when it comes to production and exchange relations. This, in turn, will result in the emergence of a network of exclusive interpersonal and reputation-based relations to resolve allocative and redistributive questions, including access to formal finance [9].

Hence, influential political players can and do affect economic outcomes, including the distribution of formal finance, both formally through red tape and informally through individual connections and interpersonal relations. Entrenched political elites may influence business environments by adopting formal rules and regulations to protect their rent-seeking interests, and create unfavorable operational constraints and obstacles for other enterprises. This can result in a culture of favoritism and bribery, which further suppresses impersonal market-based exchange and resource allocation. Because larger enterprises are more established and have more resources at their disposal to establish economically beneficial connections, smaller firms suffer more from these constraints.

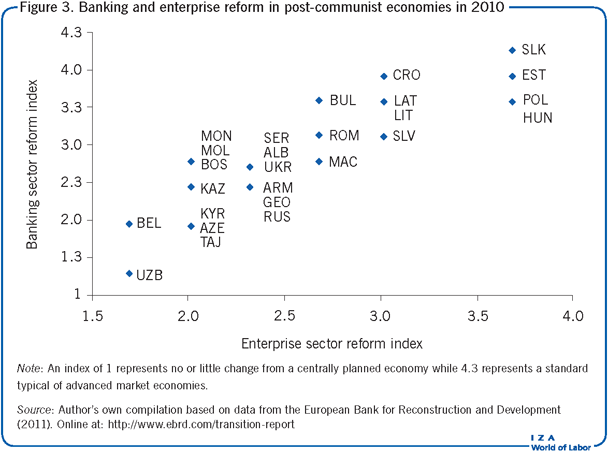

Figure 3 shows the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) indices for banking and enterprise reforms in post-communist economies. Accordingly, the assessment of banking and enterprise reforms varies across countries, with the Eastern European countries generally demonstrating better institutional reform progress in both areas.

Although most Eastern European countries might have adopted the best pro-market rules and regulations from advanced market economies, these do not immediately, or necessarily, translate into transparent and credibly functioning bureaucratic institutions. More importantly, despite the intensification of market-based exchanges and improved credibility of formal bureaucratic organizations in most post-communist economies, evidence suggests that public officials and civil servants still exploit their positions by using the rigidity of rules and regulations as an excuse for rent-seeking [10]. Moreover, according to the most recent enterprise survey data presented in Figure 1, more than one-fifth of the SMEs in Eastern Europe and more than one-third in the CIS reported relatively frequent offering of bribes to public officials.

There is growing empirical evidence to suggest that political connections play an important role in gaining access to formal finance [5], [6], [11], [12]. The most popular proxies for measuring political connectedness in these empirical studies include the proportion of top managers’ time spent with public officials, lobbying, frequency of offering bribes and gifts to public officials, holding government contracts, and whether or not top managers’ friends and/or family members work at government institutions. Despite their variability, these all have one thing in common: they attempt to measure firms’ interpersonal connectedness with public officials in bureaucratic institutions.

Although econometric studies investigating the link between political connectedness and SME access to finance have only recently emerged, the available evidence clearly and unambiguously indicates that political connectedness affects the distribution of formal finance, and that larger and wealthier enterprises benefit the most from such links. For example, using primary survey data, a case study of SMEs in Uzbekistan found that those with government connections were less likely to express a need for external finance, but were more likely to apply for bank credit, and that the application success rate was around 20% higher for politically connected SMEs [5]. Other country-level case studies from Vietnam, Slovenia, and China also found that political connectedness affected the distribution of formal finance [6], [11], [12]. A recent cross-country study based on around 14,000 SME responses from 28 post-communist economies also demonstrates that: (i) the use of interpersonal bureaucratic networks improves the chances of receiving bank credit by up to 8% and (ii) the small share of available SME credit is distributed in favor of those enterprises that capitalize on bureaucratic links. Looking at regional variation among the results, the study also found that interpersonal connectedness mattered most when formal credit was in relatively short supply, and the benefits of interpersonal links were stronger for older, wealthier, and larger SMEs [13].

Political connectedness and allocative efficiency

Alternative views exist on the influence and ultimate impact of corrupt political connectedness on allocative efficiency and social welfare, which is a key policy question. According to one line of reasoning, the impact of corruption on allocative efficiency can be positive—the so-called “helping hand” perspective. For example, under imperfect market conditions and limited rule of law, entrepreneurs may consciously and actively look for government connections hoping to gain access to resources and/or to ease various business constraints. This can then incentivize public officials to act as de facto stakeholders in businesses rather than “short-term bribe-takers,” resulting in the adoption and implementation of business-friendly regulations, hence fostering growth prospects. In addition, firms that can afford to offer (highest) bribes to gain access to scarce resources are also likely to be more successful enterprises, which ultimately results in socially beneficial outcomes [6], [10].

Critics, however, point out that this view ignores the necessarily interpersonal nature of relations between public officials and entrepreneurs, especially when bureaucratic organizations do not enjoy full credibility. They argue that interpersonal networks are used more often when rent-seeking behavior is prevalent, rules and laws are dysfunctional, and anonymous markets are suppressed—the so-called “grabbing hand” perspective [9]. Although interpersonal links require some form of eventual pecuniary reward in exchange for favors, non-pecuniary obligations are likely to dominate, as these can be recurrent and produce continuous benefits to both parties. Further, soliciting bribes is not costless for corrupt officials, even under these circumstances: there is always a danger that they may be caught in the process, implying that bureaucrats are more likely to cooperate with people they trust to minimize the risk of being caught [9], [10]. Therefore, having the right interpersonal connections becomes more valuable than simply affording explicit monetary payments as bribes.

There is limited evidence for the “helping hand” version of the conjecture, and it is specific only to China, where administrative reforms in the 1990s allowed government officials to quit bureaucracy and join the business sector. This particular policy incentivized bureaucrats to implement pro-growth reforms in China. In contrast, the list of studies finding evidence for the “grabbing hand” version of the argument is too long to list here. But, it suffices to refer to the most recent country-level case studies from countries such as Slovenia, Vietnam, and Uzbekistan, all of which find that although political connectedness improves firms’ access to formal finance, the practice is not positively associated with firm performance and growth.

The implication is that not all entrepreneurs are fortunate enough to have economically beneficial interpersonal connections with people in power, and that the most valuable of such networks can also be the most exclusive. In addition, belonging to a single network may open access to other networks,meaning some entrepreneurs will potentially be members of multiple networks. For example, entrepreneurs may gain indirect access to formal finance through their connections with government officials who network with other resource holders including bankers. The interpersonal and exclusive natures of such networks imply that a small number of strategically well-connected entrepreneurs will be able to seize a disproportionately large share of common resources and opportunities, which can result in further allocative inefficiencies. Hence, corrupt practices by official bureaucrats cannot be justified, as they rely on insider–outsider distinctions and suffocate equality of opportunities. They are, therefore, not only economically costly but arguably morally repugnant [13].

Limitations and gaps

Although the emerging literature on political connectedness provides a vital contribution to understanding of the key factors that lead to the asymmetric distribution of formal finance across enterprises of varying size and political influence, there remain some important limitations and gaps. First, despite the fact that financial development is closely associated with economic growth, and that the strength of this correlation depends on underlying institutional differences such as the effectiveness of contract enforcement and creditor protection laws, the observed empirical relationship between the two variables does not necessarily imply causation. Indeed, lack of formal finance is not the only constraint to SME growth, which also depends on owners’growth aspirations, market failures, policy, and other institutional factors. Second, some political connections are more valuable than others and further research is needed to account for this more adequately. And finally, notwithstanding the existing strong consensus about the positive impacts of improving the transparency, impartiality, and predictability of bureaucratic institutions on the efficiency of market exchanges in general, and the resource allocation process in particular, it is not easy to measure the process precisely for policy purposes.

Summary and policy advice

SMEs play an important role in terms of employment generation, poverty reduction, and contribution to economic growth. But they often lack adequate access to appropriatelypriced formal finance, which constrains their operations and growth. Traditional explanations for the unequal distribution of finance focus on market and information imperfections. A more recent approach adds an additional dimension to this phenomenon by highlighting the role of institutional and political factors in the economic process. When bureaucratic institutions lack credibility, and rules and laws are dysfunctional, rent-seeking behavior becomes prevalent as agents try to profit from the web of interpersonal relations. Growing evidence suggests that political connections play an important role in gaining access to formal finance,further exacerbating the misallocation of scarce credit resources among SMEs.

Traditional policy measures to improve the flow of formal finance to SMEs include both supply and demand side support schemes. For example, governments can offer various loan guarantee schemes to support lending to the SME sector, which allows SMEs to gain access to formal credit at cheaper rates. Governments can also offer tax breaks on bank profits earned in lending to the SME sector, thus incentivizing banks to lend more to SMEs. Also, most of the regional and international financial institutions, such as the EBRD and the Asian Development Bank, offer funds to local banks to be channeled specifically to SMEs. Although, in principle, these policies may improve the overall flow of formal finance to SMEs, which is debatable without appropriate empirical evidence, the discussed findings make a strong case against their ability to achieve equitable distribution amongst most creditworthy enterprises.The traditional measures, therefore, need to be complemented with decisive and credible reforms aimed at improving the transparency and impartiality of bureaucratic institutions in general, and eradicating corrupt and rent-seeking behavior by public office holders in particular. Such reforms could involve the development of fair and competitive remuneration schemes for government employees. These schemes might include explicit meritocratic criteria to foster longer-term career development planning, careful identification and credible punishment of corrupt officials, and continuous professional development workshops aimed at raising awareness about the consequences of corruption. Without these types of reforms, entrepreneurs will not be incentivized to use prices, rules,and regulations as signals for decision making, and will instead rely on interpersonal connections with bureaucrats, thuscontinuing to perpetrate the misallocation of scarce credit resources.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [5], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Kobil Ruziev