Elevator pitch

Multiple job-holding, or “moonlighting,” is an important form of atypical employment in most economies. New forms of work, driven by digitalization, may enable its future growth. However, many misconceptions exist, including the belief that multiple job-holders are low-skilled workers who moonlight primarily for financial reasons, or that the practice increases during economic downturns. Recent literature highlights the significant links between moonlighting and job mobility. Multiple job-holding allows for the development of workers’ skills and spurs entrepreneurship.

Key findings

Pros

Higher net income and financial security can be secured by holding multiple jobs, especially when the primary job is constrained by hours or earnings.

Task variety associated with a second job can motivate and increase work satisfaction.

A second job can increase development of new job skills.

Multiple job-holding has positive effects on future job mobility and career prospects.

Holding multiple jobs may foster increased entrepreneurship and can lead to a new job that better matches a worker's skills.

Cons

A healthy work–life balance is harder to maintain when holding multiple jobs, and a greater rate of absenteeism may occur.

Conflicts of interest may arise between multiple jobs; misappropriation of public resources can occur if the primary job is in the public sector.

Conflict of social insurance entitlements may occur when moonlighters are not, or only partially covered by different employers.

Multiple job-holding is associated with a greater risk of both workplace and non-work injuries.

Moonlighting can increase participation in the informal economy and lead to tax evasion.

Author's main message

Multiple job-holding can help workers maintain their desired standard of living when their primary job does not provide adequate hours or income. Moreover, skills acquired when moonlighting can influence subsequent occupational mobility—including a move to self-employment. However, a second job may also be associated with greater physical and mental hardship. As such, policies related to multiple job-holding should shield vulnerable workers from being exposed to precarious or informal work conditions. Beyond this protectionary role, they can also be part of a strategy that seeks to further stimulate labor market mobility and entrepreneurship.

Motivation

Multiple job-holding (MJH), also known as moonlighting, is an important form of atypical employment in many developed and developing economies. In 2015, about 8.7 million employed people in the EU had a second job in addition to their primary employment, an increase of approximately one million people compared to a decade earlier. Similarly, in the US, about 7.3 million workers held more than one job in 2015, although the trend has been steadily declining since the mid-1990s.

Recent years have seen an increase in non-standard work routines [1]. The prolonged global economic crisis has also fostered a rising trend in part-time and short-time employment contracts. Furthermore, digitalization and the rise of the gig or platform economy has further compromised traditional work arrangements in favor of new forms of work (e.g. on-call work, labor leasing, independent subcontracting, freelancing, home-based work). With such increasing risk of unstable employment in job markets, workers must hedge against uncertainty and procure a secure income. MJH is one such strategy for maintaining uninterrupted employment and gaining financial security.

Discussion of pros and cons

Prevalence of moonlighting

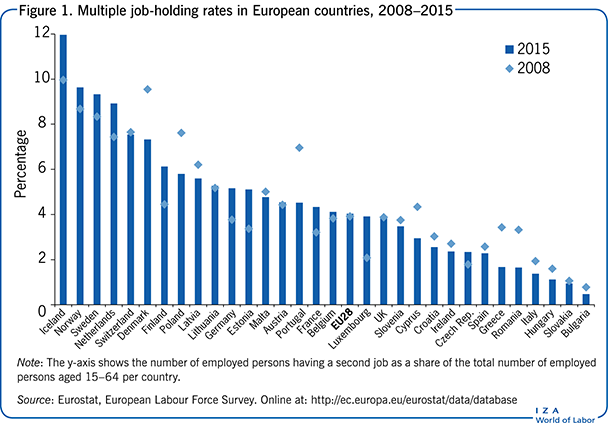

MJH affects a significant share of the adult workforce in most developed and developing economies. In 2015, 4.9% of workers in the US declared that they carried out another job in addition to their main employment. Meanwhile, 4% of the 28 EU member states’ employed population were multiple job-holders in 2015, with marked variation between member states. MJH tends to be highest in the Nordic countries—with rates as high as 12% in Iceland, 10% in Norway, 9% in Sweden, and 6% to 7% in Finland and Denmark—as well as in the Netherlands, with a rate of 9%. By contrast, less than 2% of the employed workforce holds more than one job in Southern and Central Eastern European countries such as Greece, Romania, Italy, Hungary, Slovakia, and Bulgaria (Figure 1). Similarly, there is a significant difference in moonlighting rates between US states, which tends to remain constant over time; though why this is so remains a puzzle [2]. There are also notable variations in MJH rates between regions and geographical areas in advanced labor markets, with rural or less populated areas often exhibiting higher moonlighting rates due to lower wages, fewer economic opportunities, and distinctive economic structures (e.g. higher self-employment rates).

Since the early 2000s, MJH has become more prevalent in several countries, rising by as much as 3% in the Netherlands, Germany, and Luxembourg. By contrast, the share of the employed population holding a second job has declined most markedly in Denmark (–3.3 percentage points), Romania (–3 points), Poland (–2.4 points), and Portugal (–2.3 points). In the US, the national MJH rate has also decreased over time, falling by as much as 20% over the past two decades—more so for men than women. Some have argued that this declining trend is largely driven by a reduced inflow of workers into second jobs, in particular a dwindling tendency for full-time workers to take on a second job. Nevertheless, others point out that in the US Current Population Survey estimates increases in MJH are understated and decreases overstated due to significant measurement issues that arise as a result of the rotation of different samples as part of the survey [3]. Because of the typically short duration of moonlighting, MJH rates are larger (by about 27.5%) when calculating them on the basis of a group of individuals who have just entered into the survey, as opposed to using the whole sample. As much as a quarter of the measured decline in the US MJH rate can therefore be attributed to measurement bias, while the residual reflects the changing labor supply behavior of US workers in recent decades.

Workers holding multiple jobs tend to work an additional 11 to 12 hours a week on average relative to single job-holders (typically about 13 to 14 weekly hours are spent in the second job). Though the mean number of hours has fallen slightly during the recent economic downturn in both the US and EU economies, more than a quarter (27% in the EU and 28% in the US) of total work hours among multiple job-holders in the EU and US are still spent at a second job [4].

A number of factors are associated with a higher incidence of MJH. Moonlighting tends to affect prime-aged people (35–54) and is moderately more common among women than men. This usually mirrors the fact that individuals whose primary job is part time are more likely to take up another job, presumably because they feel underemployed in their first job. The portfolio of jobs adopted by male and female moonlighters also tends to differ, with female moonlighters being more likely to work two part-time jobs while male moonlighters typically hold one full-time and one part-time job or are self-employed.

Somewhat surprisingly, higher-educated workers are more likely to hold multiple jobs than less-educated ones. This challenges the conventional wisdom that the majority of moonlighters are only low-wage earners or people from financially strapped households. The occupation and industry of the primary job is also relevant. Manual workers, particularly those working in the manufacturing industry, craftsmen, and machine assemblers are less likely to hold a second job. By contrast, a considerable proportion of workers in professional and service occupations or in arts/entertainment, education, and health/social work hold more than one job.

The pro-cyclical nature of moonlighting

A popular perception is that MJH is countercyclical (i.e. it increases during economic downturns), as one might expect that workers would be more inclined to search for a second job at times of economic hardship. During economic recessions, workers may seek to take an additional job if they have experienced a reduction in work hours, a cut in salary in their primary job, or if another member of their household has lost their job. Under these circumstances, standard labor supply theory would predict that individuals could respond by substituting leisure hours for work hours. However, this logic fails to take into account that prolonged recessions will be accompanied by a significant reduction in product and labor market demand, which will shrink the pool of available job opportunities, including secondary jobs. In this case, MJH will be procyclical; in other words, it will decline during recessions.

The available evidence on MJH's responsiveness to macroeconomic conditions is limited and inconclusive. However, recent studies show that MJH is either procyclical, specifically among females—or largely unrelated to economic conditions, especially when accounting for variation in MJH within local labor markets and over time [5].

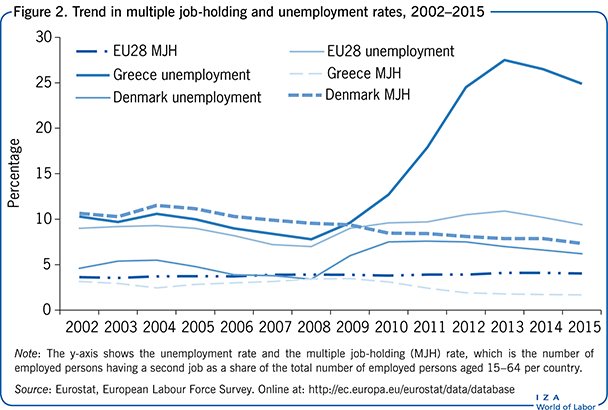

Figure 2, for instance, depicts the time series of MJH and unemployment rates from 2002 to 2015 for the entire EU28 and for two specific countries, Greece and Denmark. The figure demonstrates that the mean EU28 MJH rate has remained constant at 4% over the past 15 years, despite the spike in unemployment resulting from the 2008 Great Recession. Moreover, the evidence from Greece, a country where the severity of rising unemployment constitutes the closest proxy to a natural economic experiment, highlights that MJH decreased as economic conditions worsened. Nevertheless, Denmark's MJH rate shows a sustained decrease since the mid-2000s, which appears to be largely independent of the business cycle. This highlights the importance of carefully understanding the country-specific institutional context (e.g. marginal tax rates, social insurance benefits, size of informality and undeclared work, etc.) when interpreting moonlighting trends across diverse economies.

The motives behind moonlighting

The literature on the motives underlining MJH has identified several potential causes:

Individuals may face constraints on their hours or earnings in their primary job; i.e. they may be willing to increase their labor supply but are not offered the chance to do so in their primary occupation (e.g. due to working time regulations, short-time working contracts at times of low economic demand, marginal tax rates/social insurance credits or lack of a minimum wage affecting total earnings in the primary job). This situation may accentuate financial constraints to the individual or his/her household, including for salaried workers who do not face hours constraints per se in their job, but whose wages fall short of their target income. This is also often referred to as the financial motive.

Individuals who experience negative financial shocks may choose to find a second job in order to smooth their consumption, as an alternative to precautionary savings [6].

Employees faced with job insecurity may use second jobs as an insurance device to hedge against the risk of primary job loss and to diversify their options of remaining in the labor market by holding multiple employments [7].

Individuals may derive utility from their second job that differs to that received from their primary employment (e.g. some people may be employed as teachers in their first job but in the evening they sing in a band). Job heterogeneity might thus be another motive to moonlight [8].

Workers may decide to take on another job as a way to gain new occupational skills that will enable them to transfer to an alternative line of work [4], [9]. MJH can facilitate transitions between occupations or be an effective incubator of entrepreneurial activities, increasing an individual's chances of changing careers. This theory is related to the job heterogeneity motive, but focuses more on the investment rather than consumption element of moonlighting.

One would expect to see a negative relationship between employees’ primary job earnings/hours and their chances of taking multiple jobs on the basis of the hours constraints theory. However, the heterogeneous job motive recognizes that individuals may select a second job for reasons unrelated to potential primary job hours or earnings.

Much of the early literature on MJH favored the hours constraints motive, as it was confirmed that the number of hours worked in second jobs was inversely related to the hours worked and earnings in primary jobs. It was also shown that husbands’ tendency to moonlight may be affected by rising household income; for example, when their spouses participate more in the labor market, husbands’ moonlighting rates decline. It nevertheless seems clear that it is not only the wage level of the primary job but also the size of a wage increase that is critical for lowering the take up of second jobs, especially among the lower-paid. This was evident, for instance, when the extra pay offered by the newly introduced minimum wage in the UK in 1999 had an insignificant impact on MJH rates [10]. This may be because the absolute increase in weekly income generated by the higher minimum wage was insufficient relative to the income threshold required to induce low-paid individuals to stop working a second job.

Some authors argue that if workers moonlight because they face hours constraints in their main job, then they should have shorter moonlighting spells compared to those who have taken up a second job for non-financial, intrinsically satisfying, reasons. Indeed, the traditional hours constraints explanation fails to account for the fact that, over time, workers can avoid barriers in their primary job by searching for a new job. In this regard, longitudinal evidence from the UK has shown that moonlighting can be persistent over time [8], [9]. This has cast further doubt on the hours constraints theory as a sole explanation for MJH.

Little evidence has been found to support the view that workers may moonlight to hedge against job insecurity in their main job [7]. Some literature even suggests that MJH tends to be more prevalent among public sector employees and those who hold permanent contracts [11]. This implies an indirect positive relationship between job security and moonlighting; workers will decide to take a second job if their main job provides them with some minimum degree of certainty.

More recent empirical research has thus come to increasingly recognize that “it is not all about the money” [12]. Many different motives have been found to underpin an individual's decision to moonlight, most notably that some workers enjoy the non-financial aspects of their secondary jobs. Holding multiple jobs can be, for many, a personal strategy for finding or regaining job satisfaction, through engaging in more challenging types of work or skills growth.

Multiple job-holding, skills, and labor market mobility

Linked to the job heterogeneity motive discussed above, the latest wave of scientific research has been more focused on MJH's potential to facilitate labor market transitions. Such research acknowledges the important role of moonlighting as a means of developing new or improved skills that can lead to a change in job or career or may spur self-employment [4], [9]. Under this assumption, MJH should be predominantly transitory rather than permanent. Nevertheless, the duration of moonlighting can be lengthy if job availability is scarce in the short-term, affecting a worker's ability to switch jobs, while also depending on the degree to which skills are transferrable between occupations.

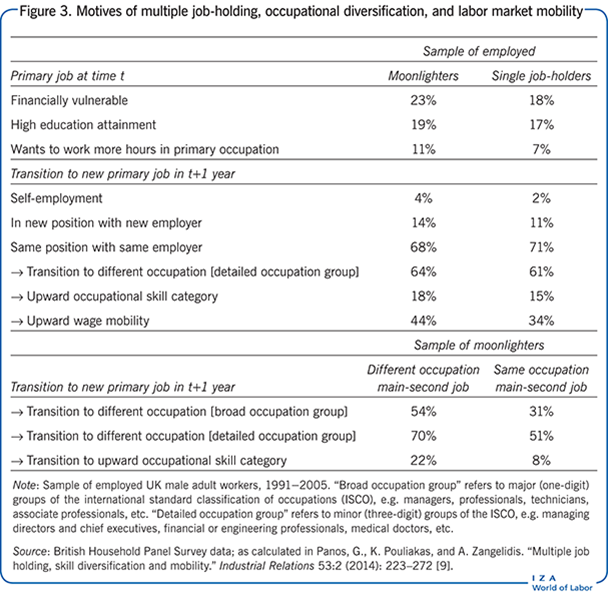

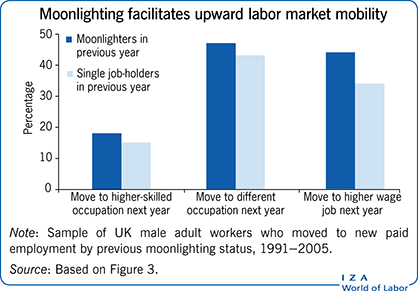

A recent UK study that tracked male employees from 1991 to 2005 examined the links between job experience accumulated in their primary occupation, the incidence of moonlighting and the degree to which the relationship between the primary and secondary job is associated with subsequent labor market mobility [9]. The study confirms there is much diversity in the underlying motives of workers who have more than one job. However, it also shows that in the following year, moonlighters are twice as likely to become self-employed and 35% more likely to move into a new job with a new employer, compared to employees who do not moonlight (see Figure 3). Moonlighters are also 17% less likely to become unemployed or inactive.

The research further highlights that “temporary moonlighters” (those in a second job for less than one year) have an almost 25% greater chance of securing a new primary job in the subsequent year, compared to non-moonlighters. By contrast, “serial moonlighters” (those in a second job for more than one year) appear to be less inclined to use a second job as a human capital investment strategy and tend to enjoy the consumption value of a second job instead.

The study further explores what type of occupation individuals select in their second job in relation to their main occupation. It is striking that about eight in ten moonlighters in the UK have a second job that is in a different occupation to their primary one. The choices workers make as multiple job-holders can thus encourage job mobility and affect the type of job selected in their new primary employment.

Specifically, moonlighters who diversify their job skills between their primary and secondary employments have greater chances of moving to a new primary job and making the transition to a different occupation altogether in their next primary employment. Furthermore, moonlighters are more likely to move into higher-paid new primary jobs. The transition tends to be accompanied by an upward movement to a more skilled position when moonlighters have diversification between their primary and second job.

The hazards of multiple job-holding

Despite the fact that MJH can facilitate development of new job skills and spur entrepreneurship, it is important for policymakers to consider its impact on the health and safety of workers as well as their work–life balance. Working in multiple jobs has been found to be associated with an increased risk of work and non-work injury, which includes higher absenteeism rates. This is presumably due to increased fatigue, lack of sleep, or additional physical and mental stress from being exposed to disruptive or irregular work environments and timetables [13]. Additional psychosocial stress has also been seen as a result of the combined impact and interaction of multiple jobs.

Another important concern in relation to moonlighting activities is the fact that, particularly in transition economies, a significant share of these activities takes place as part of the informal economy. For instance, moonlighting had been said to account for about 70% of Russian households’ income from informal activities in the early 2000s and about eight in ten secondary jobs were in the informal sector. This has important implications for tax revenues and inhibits a country's ability to improve its social security system and quality of public services as much as it would if these activities were conducted in the formal sector. Furthermore, informal settings often offer fertile ground for the misappropriation of public resources by individuals who are employed in the public sector as part of their primary employment but who engage in private enterprise when moonlighting (especially prevalent among medical or teaching professionals).

The advent of digitalization has also facilitated the proliferation of various online forms of MJH, most notably crowdsourcing work and other (paid or unpaid) work on online platforms. Although robust evidence about the labor market status of workers employed in such alternative work arrangements is still lacking, reports of haphazard working arrangements (e.g. on-call work), inferior working conditions (e.g. employer non-compliance with minimum wage and overtime regulations), and absence of social insurance entitlements for such multiple job-holders tend to be frequent.

Limitations and gaps

Even though recent research has made significant progress investigating the underlying motives for why individuals hold multiple jobs, significant challenges remain. Existing national surveys collect only limited information about the different forms of MJH, which are likely to evolve due to the ongoing digitalization process. They also tend to focus only on a limited set of second job characteristics (e.g. professional status, industry, hours). Just a few standard surveys collect information about second job income, type of occupation (measured in the US Current Population Survey but not necessarily in European labor force surveys), or training and skills accumulation in secondary employment. Moreover, there is a need to exercise care when interpreting data on MJH due to the typically small sample sizes and low data reliability, which is linked to moonlighters’ tendency to misreport second job data (like income).

Researchers still lack understanding of the determination and structure of second job wages and their link with existing or newly developed human capital and skills. Furthermore, longitudinal or quasi-experimental analysis that can identify convincing causal links between the incidence of MJH and subsequent labor market and health outcomes is still in its infancy.

Finally, recent data from the OECD's Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) indicate that, on average, moonlighters have higher average levels of foundation skills (i.e. numeracy, literacy, digital skills) than single job-holders. The positive multiple job-holding skills premium remains unaffected when individual characteristics (e.g. education, age, and gender) as well as characteristics of the main job (e.g. primary job hours and earnings) are taken into account. The premium is also robust after accounting for the differential learning aptitudes of multiple job-holders, the education level of their parents, and their participation in adult learning during the previous year, variables which proxy for past levels of acquired human capital. An interesting avenue for future research is thus to decouple the extent to which the higher skills of moonlighters reflect past human capital decisions from that which can be attributed to their secondary job experience.

Summary and policy advice

MJH can be an important source of supplementary income for individuals faced with hours or earnings constraints in their primary job. Important human capital spillover effects also take place between primary and secondary employment, inducing a positive association between MJH, job mobility, and subsequent occupational options. Individuals can use MJH as a conduit for obtaining new skills and expertise and a stepping stone to a new career path, including self-employment. Individuals who choose a different occupation in their second job relative to their main one are more likely to change jobs altogether and to have a different type of work in their subsequent primary position.

However, having more than one job is usually also a path taken by people who live in households that struggle to make ends meet or by those faced with unexpected economic shocks. Even though for such vulnerable workers MJH is likely to be a symptom of wider difficulties to sustain a decent standard of living with a single job, a second job, especially in less developed economies, may be associated with greater physical and mental hardship, or exposure to precarious or informal working conditions.

Policy intervention may not be warranted in general, though in cases where market failures may necessitate some action it is critical that policy approaches be carefully customized to account for the underlying motives and conditions of MJH. For instance, when MJH activity takes place at the margins of the informal economy, then the policy priority should focus on tackling undeclared work, safeguarding lower-threshold income levels, and ensuring appropriate health and safety standards.

However, researchers are increasingly acknowledging that MJH is not only performed by the low-income worker. Recognizing and validating the skills that workers acquire as part of their moonlighting experiences can be a useful means of increasing job mobility, which is a key aim of employment and skills policy agendas. Moreover, MJH could be considered within the arsenal of policy measures for stimulating entrepreneurial activity in contemporary labor markets.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Professor I. Theodossiou (University of Aberdeen), Dr A. Zangelidis (University of Aberdeen), and Professor G. Panos (University of Glasgow) for their long-standing research collaboration on MJH. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [9]. Support in research capacity by the University of Aberdeen is gratefully acknowledged. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect in any manner the views of the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP).

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Konstantinos Pouliakas

Defining and measuring multiple job-holding

Source: Hirsch, B. T., and J. V. Winters. Rotation Group Bias in Measures of Multiple Job Holding. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10245, 2016.