Elevator pitch

Multiple job-holding, or “moonlighting”, is an important form of atypical employment in most economies. New forms of work, driven by digitalization, may enable its future growth. However, many misconceptions exist, including the belief that multiple job-holders are only low-skilled individuals who moonlight primarily for financial reasons, or that the practice increases during economic downturns. Recent literature highlights the significant links between moonlighting and job mobility. Multiple job-holding allows for the development of workers’ skills and spurs entrepreneurship.

Key findings

Pros

Higher net income and financial security can be secured by holding multiple jobs, especially when the primary job is constrained by hours or earnings.

More task variety associated with a second job can motivate and increase work satisfaction.

A second job can increase development of new job skills.

Multiple job-holding has positive effects on future job mobility and career prospects.

Holding multiple jobs may foster increased entrepreneurship and can lead to a new job that better matches a worker’s skills.

Cons

Inferior job quality, including adverse working conditions, haphazard working hour arrangements and absence of social insurance entitlements, form a risk for multiple job-holding.

Multiple job-holding is associated with a greater risk of both workplace and non-work injuries.

Multiple job-holding can deplete physical and psychological well-being and foster identity conflict.

The transition to more than one job can compromise work-life balance, especially for those with children.

Moonlighting can compromise organizational commitment.

Author's main message

Multiple job-holding can help workers maintain their desired standard of living when their primary job does not provide adequate hours or income. Moreover, skills acquired when moonlighting can influence subsequent occupational mobility—including a move to self-employment. However, a second job may also be associated with greater physical and mental hardship and overall lower job-quality. As such, policies related to multiple job-holding should shield vulnerable workers from being exposed to precarious or informal work conditions. Beyond this protectionary role, they can also form part of a strategy that seeks to further stimulate labor market mobility and entrepreneurship.

Motivation

Recent decades have seen an increase in non-standard and new forms of work, including irregular, independent or remote work [1]. Multiple job-holding (MJH), also known as “moonlighting”, is an important form of atypical employment. In 2018, about 9.1 million employed people in the EU had a second job, up by almost 1.5 million compared to 2005, corresponding to about 4% of the European workforce. Similarly, in the US about 5% of workers held more than one job in 2018. Such estimated rates obtained from official sources are likely to underestimate the true occurrence, considering the challenges involved in accurately measuring rotating, short-duration or project-based jobs or other irregular employment combinations.

Discussion of pros and cons

Prevalence of moonlighting

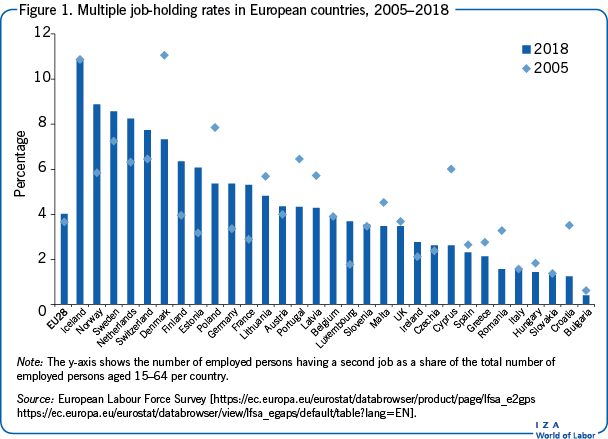

MJH affects a significant share of the adult workforce in most developed and developing economies. In 2018, 5% of workers in the US declared that they carried out another job in addition to their main employment. Meanwhile, 4% of the EU employed population were multiple job-holders (MJHs) in 2018, with marked variation between countries. MJH tends to be as high as 7–11% in various Nordic and continental European countries (e.g. Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark). By contrast, about 2% or less of the employed workforce holds more than one job in various Southern and Central Eastern European countries such as Greece, Romania, Italy, Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia and Bulgaria (see Figure 1). There are also notable variations in MJH rates between regions and geographical areas [5].

Since 2005, MJH rates across European countries have exhibited diverging trends. While one group of countries (e.g. Norway, Estonia, France, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Luxembourg) have seen a substantial increase during the 2005–2018 period, others (e.g. Denmark, Poland and Croatia) have seen a steady decline.

In the US, the national MJH rate, as measured by the Current Population Survey (CPS), has also decreased by as much as 20% over the past two decades. Some have argued that this declining trend is largely driven by a reduced inflow of workers into second jobs, in particular of full-time and non-employed workers. Others point out that the CPS estimates of MJH are affected by significant measurement issues because of the rotation of survey samples and alternative interview modes (e.g. face-to-face vs. phone interviews) [3].

Using alternative series based on administrative data reveals that the US MJH rate even seems to have been trending upward in recent decades. This upward trend may be consistent with recent trends in labor markets, including a growing number of part-time jobs in industries; stagnation of wage growth at the bottom end of the earnings distribution; the ‘renaissance of self-employment’ and technological developments that have made it less costly to find and take on a second job [4].

MJH is related to higher total work hours, with estimates varying between an additional 4 to 12 hours a week on average relative to single jobholders. European workers holding multiple jobs tend to work an average 32 hours per week in the main job as compared to 37 for those with a single job. However, by taking on additional jobs, the average work week of European MJHs rises to 41 hours in total, and to as much as 46 hours for males. Though the mean number of weekly work hours has fallen in recent decades in both the US and EU, more than a quarter (about 28%) of total work hours among MJHs are spent at a second job [6].

Several factors are associated with a higher incidence of MJH. Although some studies find that workers in mid-career (aged 30 to 49) have a relatively high MJH rate, recent US evidence has showed it monotonically declining with age [4]. Holding more jobs is more common among women than among men and over time a widening gender difference is observed in both Europe and the US. The relatively high prevalence of women among MJH usually mirrors the fact that individuals whose primary job is part-time are more likely to take up another job, presumably because they feel underemployed in their first job. The industrial distribution and portfolio of jobs also tends to differ by gender, with female moonlighters being more likely to work two part-time jobs, while male moonlighters typically hold one full-time and one part-time job or combine dependent employment with self-employment [7].

Higher-educated workers are more likely to hold multiple jobs than less-educated ones. This challenges the conventional wisdom that most moonlighters are only low-wage earners or people from financially strapped households. The occupation and industry of the primary job is also relevant. Manual workers, particularly those working in the manufacturing industry, craftsmen, and machine assemblers are less likely to hold a second job and their share has dwindled over time. By contrast, a considerable proportion of workers in professional and service occupations or in arts/entertainment, education, and health/social work hold more than one job.

Reflecting the increasing flexibility of labor markets, MJH has become particularly pronounced among workers in alternative employment arrangements. Over the past two decades, most MJHs have steadily moved away from typically combining a full-time with a part-time job to holding multiple part-time job constellations or jobs that involve flexible employment terms (e.g. temporary/no contracts) [7].

The procyclical nature of moonlighting

A popular perception is that MJH is countercyclical, as one might expect that workers would be more inclined to search for a second job at times of economic hardship, when they might experience a reduction in work hours, a cut in salary in their primary job, or if another member of their household has lost their job. Under these circumstances, standard labor supply theory would predict that individuals could respond by substituting leisure for work hours, including in a second job if it is not possible to do so in one’s primary employment. However, this logic fails to consider that prolonged recessions are accompanied by a significant reduction in product and labor market demand, which shrinks the pool of available (including secondary) job opportunities. In this case, MJH can be procyclical; in other words, it declines during recessions and rises in expansions.

The available evidence on MJH’s responsiveness to macroeconomic conditions is limited and still inconclusive. Recent studies from the US show that MJH is either procyclical, specifically for females, or largely unrelated to economic conditions, especially when accounting for variation in MJH within local labor markets and over time [4]. Evidence from other countries (e.g. Canada) further supports that the lack of MJH cyclicality during recessions masks a large drop in both inflows (due to fewer jobs available in the economy) and outflows (diminishing propensity to give up one’s second income source). To explain divergent cyclical reactions of MJH rates across economies, in-depth understanding of country-specific institutional context (e.g. marginal tax rates, social insurance benefits, size of informality) is required.

The motives behind moonlighting

The literature on the motives underlining MJH has identified several potential causes. These typically reflect so-called ‘push’ or ‘pull’ motivational factors, such as taking up more than one job out of economic necessity versus other intrinsically satisfying reasons:

Individuals may face constraints on their hours or earnings in their primary job; i.e., they may be willing to increase their labor supply but are not offered the chance to do so in their primary occupation (e.g. due to working time regulations, short-time working contracts, marginal tax rates/social insurance credits or lack of a minimum wage in the primary job). This situation may accentuate financial constraints to the individual or his/her household, including for salaried workers who do not face hours constraints per se in their job, but whose wages fall short of their target income. This is also often referred to as the financial motive or deprivation/ constraint hypothesis.

Individuals who experience negative financial shocks may choose to find a second job to smooth their consumption, as an alternative to precautionary savings [8].

Employees faced with job insecurity may use second jobs as an insurance device to hedge against the risk of primary job loss and to diversify their options of remaining in the labor market by holding multiple employments [9].

Individuals may derive utility from their second job that differs to that received from their primary employment (e.g. some people may be employed as teachers in their first job but in the evening they sing in a band). This is referred to as the heterogeneity motive or energic/ opportunity hypothesis [10].

Workers may decide to take on another job to gain new occupational skills that will enable them to transfer to an alternative line of work [6], [11]. MJH can facilitate transitions between occupations or be an effective incubator of entrepreneurial activities, increasing an individual’s chances of changing careers or starting up new business ventures. This theory is related to the job heterogeneity motive but focuses more on the investment rather than consumption element of moonlighting.

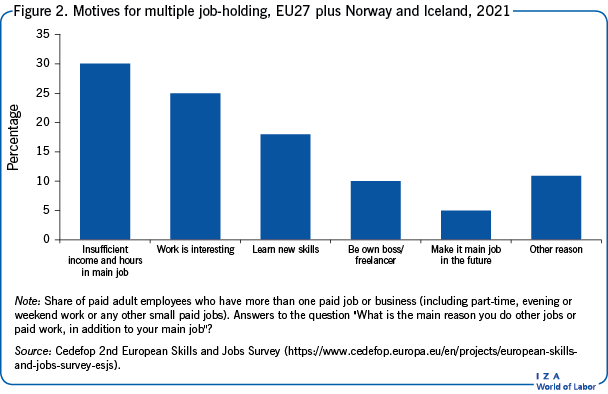

Overall, one would expect to see a negative relationship between employees’ primary job earnings/ hours and their chances of taking multiple jobs on the basis of the hours constraints theory. However, the heterogeneous job motive recognizes that individuals may select a second job for reasons unrelated to potential primary job hours or earnings, recognizing that “it is not all about the money”. Holding multiple jobs can be, for many, a personal strategy for finding or regaining job satisfaction and personal fulfilment, through engaging in more or other challenging types of work or skills growth (see Figure 2). On many occasions, MJH motivations and experiences are likely to be a mix of both push and pull factors, to varying degrees.

Multiple job-holding: depletion or enrichment?

Rooted in the underlying diversity of motives of MJH is an attempt to further understand its consequences in terms of individuals’ labor market outcomes, but also its impact on their organizations and families. Investigating whether occupying multiple job roles is associated with resource loss (“depletion”), such as work-life conflict, role conflict or physical health deterioration, or resource gain (“enrichment”), such as higher income but also greater task variety, work satisfaction and career progression opportunities, has been the focus of most recent MJH literature [2].

Financial rewards of MJH

Much of the literature, early and contemporary, on MJH has provided convincing evidence in favor of the hours constraints motive. It is generally confirmed that MJHs have lower mean earnings in their main job and that the likelihood of working in more than one job, or the number of hours worked in them, is inversely related to the hours worked and earnings in primary jobs. It has also been shown that the tendency to moonlight may be affected by rising net household income and that MJHs tend to have a higher risk of household poverty [7]. It is therefore clear that working multiple jobs is a “make ends meet” strategy many individuals adopt to counter underemployment and mitigate financial constraints. In fact, panel evidence tends to corroborate that those who make a transition from a single to multiple job generally enjoy upward wage mobility, thereby partly mitigating their financial vulnerability [11], [12].

Hedging against job insecurity and precarious work

Initial evidence failed to support the view that workers may moonlight to hedge against job insecurity in their main job [9]. Some literature from the UK even suggests that MJH tends to be more prevalent among public sector employees and those who hold permanent contracts. This implies an indirect positive relationship between job security and moonlighting; workers decide to take a second job if their main job provides them with some minimum degree of certainty.

Recent longitudinal analyses from several European countries, spanning across almost two decades, have revealed that workers with non-standard, precarious, contracts in their primary job have a significantly higher propensity to moonlight [12]. MJHs in 28 European countries are also found to have on average higher primary job insecurity, compared to those holding single jobs.

Multiple job holding, skills and labor market mobility

Overall, MJHs experience inferior career development opportunities in their main job compared to those with a single job. And while they work in main jobs characterized by a wider scope for autonomy, discretion and skill development, such job quality premiums are absent for MJHs with non-standard contracts in the primary job [7].

Linked to the job heterogeneity motive discussed above, a latest wave of scientific research has focused on MJH’s enriching potential to facilitate labor market transitions and career advancement. Such studies acknowledge the important role of moonlighting as a means of developing new or improved skills that can lead to a change in job or career [6], [11].

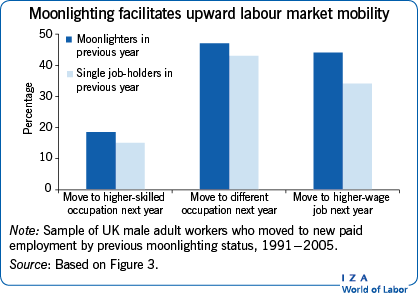

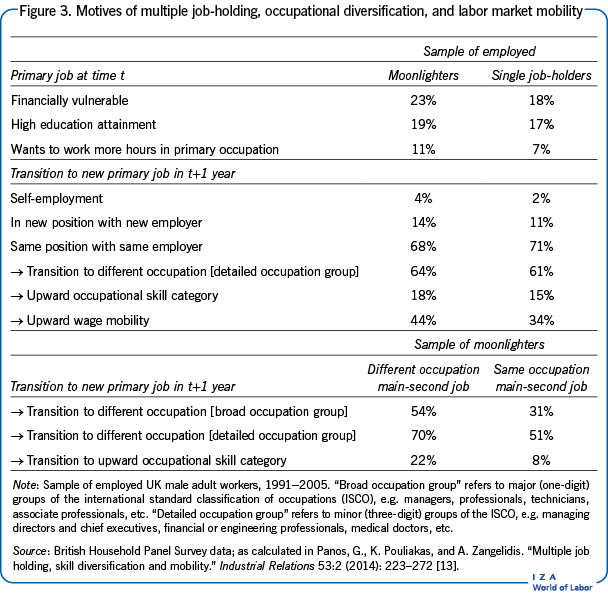

A landmark UK study that tracked male employees from 1991 to 2005 examined the links between job experience accumulated in their primary occupation, the incidence of moonlighting and the degree to which the relationship between the primary and secondary job is associated with subsequent labor market mobility [11]. The study confirms there is much diversity in the underlying motives of workers who have more than one job. However, it also shows that in the following year, moonlighters are twice as likely to become self-employed and 35% more likely to move into a new job with a new employer, compared to employees who do not moonlight (see Figure 3).

The study further explores what type of occupation individuals select in their second job in relation to their main occupation. Moonlighters who diversify their job skills between their primary and secondary employments have greater chances of moving to a new primary job and making the transition to a different occupation altogether in their next primary employment. Furthermore, moonlighters are more likely to move into higher-paid and more skilled new primary jobs.

It is important to highlight that literature investigating the dynamic mechanisms and consequences of MJH transitions is generally scarce. Evidence based on UK data does not necessarily hold in other labor market contexts; for instance, Dutch and German workers making a transition to MJH fail to experience as significant upward wage mobility as their UK counterparts [12].

The hazards of multiple job-holding

Even though MJH can facilitate development of new job skills and spur entrepreneurship, it is important for policymakers to consider its depleting effects, such as its impact on the physical and psychological health and safety of workers. Working in multiple jobs has been found to be associated with an increased risk of work and non-work injury, which includes higher absenteeism rates. This is presumably due to increased fatigue, lack of sleep, or additional physical and mental stress from being exposed to disruptive or irregular work environments and timetables [2]. Additional psychosocial stress and identity conflict has been seen as a result of the combined impact and interaction of multiple jobs.

Working in more than one job is also likely to affect individuals’ work-life balance. Working hours are higher, leaving less time for family and social activities. Overall well-being seems to deteriorate for workers who make a transition into MJH while having children [12].

In general, reports of inferior job quality, including adverse working conditions, haphazard working hour arrangements (e.g. on-call work), employer non-compliance with minimum wage and overtime regulations and absence of social insurance entitlements for MJHs tend to be frequent. Further concerns in relation to moonlighting activities in literature include lower organizational commitment and role conflict between primary and secondary roles. Particularly in transition or less developed economies, a significant share of these activities takes place as part of the informal labor market, with significant implications for misappropriation of public resources.

The degree to which individuals experience such negative, depleting effects from MJH tends to depend on the capacity of individuals to manage role conflict, employing boundary management and identity-based strategies that can foster greater enrichment [2].

Limitations and gaps

Even though recent research has made significant progress investigating the underlying motives for why individuals hold multiple jobs, significant challenges remain. Existing national surveys tend to underestimate the incidence of MJH and collect only limited information about the different forms of MJH, which are likely to evolve due to ongoing digitalization and gig work. They also tend to focus only on a limited set of second job characteristics (e.g. professional status, industry, hours). Just a few standard surveys collect information about second job income, type of occupation, or training and skills accumulation in secondary employment, let alone further indicators of second job quality. Extending the range of both quantitative and qualitative data collection methodologies focused on MJH is imperative.

Longitudinal or quasi-experimental analyses that can identify convincing causal links between MJH and subsequent labor market outcomes, with underlying motivations as mediators, are still scarce and limited to a few countries. A recent study that exploits data from a unique reform in Germany, which allowed workers to hold small, secondary jobs tax-free, is a notable example of an identification strategy that decouples the importance of the hours and financial motive for taking-up multiple jobs [13]. A promising avenue for causal inference could also be in the area of dynamic design analyses (e.g. experience sampling methods).

Another interesting avenue for future research is to distinguish the extent to which moonlighters’ skills reflect past human capital decisions or those acquired as part of their secondary job experience. In general, understanding and measuring the extent of human capital complementarities and spill-overs between primary and different secondary job roles, including entrepreneurial pursuits, and their influence on labor market outcomes, is a promising field for further investigation.

MJH literature has generally neglected a key actor of the employment relationship, namely the organization. Future studies should aim to further investigate the suitability of different roles and human resource management tactics to minimize depletion and maximize enrichment [2].

Summary and policy advice

MJH can be an important source of supplementary income for individuals faced with hours or earnings constraints in their primary job. Important human capital spill-overs also take place between primary and secondary employments, inducing a positive association between MJH and job mobility. Individuals can use MJH as a conduit for obtaining new skills and expertise and a stepping stone to a new career, including self-employment. Individuals who choose a different occupation in their second job relative to their main one are more likely to change jobs altogether in their subsequent primary employment.

However, having more than one job is usually a path taken by people who live in households that struggle to make ends meet or by those wishing to compensate for primary jobs of inferior job quality. Even though MJH is likely to be a symptom of wider difficulties to sustain a decent standard of living with a single job for such vulnerable workers, a second job, especially in less developed and segmented labor markets, may be associated with greater physical and mental hardship, or exposure to precarious or informal working conditions. Enrichment effects associated with holding more than one job are generally less applicable to workers on precarious contracts in their main employment. Increasing work fragmentation in labor markets has altered the composition of MJH, including an ever-greater bundling of multiple part-time jobs or dependent and (solo)self-employed employments, which is likely to translate into more MJHs who are subject to labor market uncertainty and volatility.

Policy intervention may not be warranted in general, though in cases where market failures may necessitate some action it is critical that it is carefully customized to account for the underlying motives and conditions of MJH. For instance, when MJH activity takes place at the margins of the informal economy or in segmented labor markets, then the policy priority should focus on tackling undeclared and precarious work, safeguarding lower-threshold income levels, and ensuring appropriate health and safety standards.

Recognizing and validating the skills that workers acquire as part of their moonlighting experiences can be a useful means of increasing job mobility. Moreover, MJH could be considered within the arsenal of policy measures for stimulating entrepreneurial activity in contemporary labor markets.

With an increasing share of the workforce combining different types of dependent and self-employed experiences, jobs or tasks/projects in the future, it is important for social insurance, employment and training policies to treat individuals’ employment biographies as a continuum, rather than as discrete work episodes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank several anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The authors also thank Professor I. Theodossiou (University of Aberdeen), Dr. A. Zangelidis (University of Aberdeen), Professor G. Panos (University of Glasgow) and Dr. K. Schulze Buschoff (WSI Institute of Economic and Social Research and Free University Berlin) for their long-standing research collaboration on MJH. Previous work of the authors contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article i.e. [7], [11], [12]. Support in research capacity by the Universities of Aberdeen and Amsterdam is gratefully acknowledged. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect in any manner the views of the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) or the University of Amsterdam. Version 2 of the article updates data and figures, adds a new figure 2 and findings on financial rewards and hedging. It adds new Further readings and Key references [2], [4], [7], [12], and [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Konstantinos Pouliakas and Wieteke Conen

Defining and measuring multiple job-holding

For instance, in some accounts MJH rates in the US have been reported as high as 11% (BLS American Time Use Survey) or 35% , in contrast to the 5–6% gleaned from the BLS CPS. Similarly, when allowing respondents to indicate if they engage in other occasional additional paid jobs, the EU MJH rate rises to an average of 7–8%, in contrast to the 4% indicated by the EU LFS.

Source: [2], [3], [4].