Elevator pitch

Before the great recession of 2008–2009, the “flexicurity” model (with flexibility for firms to adjust their labor force along with income security for workers through the social safety net) attracted attention for its ability to deliver low unemployment. But how did it fare during the recession, especially in Denmark, which has been highlighted as having a well-functioning flexicurity model? Flexible hiring and firing rules are expected to lead to large adjustments in employment in a recession. Did the high rate of job turnover continue or did long-term unemployment rise? And did the social safety net become overburdened?

Key findings

Pros

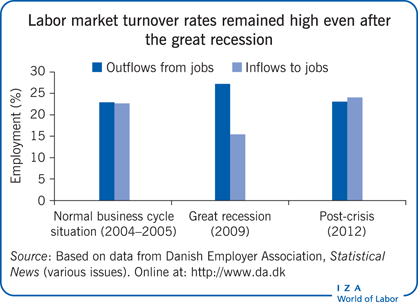

High rates of flows into and out of jobs enable firms to more readily adjust labor inputs to the business cycle and structural changes.

High job turnover rates make it easy for most unemployed workers to find jobs, implying that most unemployment spells are short.

In the wake of the great recession, there has been no steep increase in long-term unemployment and no signs of increased structural unemployment.

It is fairly easy for youth to enter the labor market, and the youth unemployment rate is relatively low.

Cons

Reconciling unemployment support with job-search incentives is challenging and places a heavy burden on active labor market policies.

The flexicurity model risks encouraging excess turnover of labor.

The system reduces incentives for firm-specific training.

Public finances are sensitive to the employment level, and for the system to function in a crisis, governments must ensure adequate fiscal space.

There is a high risk that low-educated workers will be marginalized in the labor market.