Elevator pitch

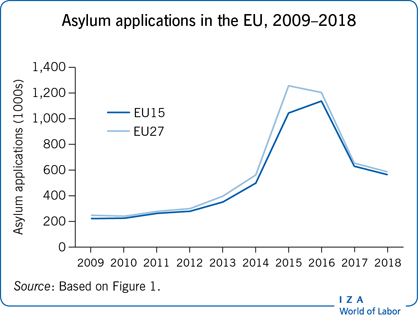

The migration crisis of 2015–2016 threw the European asylum system into disarray. The arrival of more than two million unauthorized migrants stretched the system to its breaking point and created a public opinion backlash. The existing system is one in which migrants risk life and limb to gain (often unauthorized) entry to the EU in order to lodge claims for asylum, more than half of which are rejected. Reforms introduced during the crisis only partially address the system's glaring weaknesses. In particular, they shift the balance only slightly away from a regime of spontaneous asylum-seeking to one of refugee resettlement.

Key findings

Pros

The European migration crisis of 2015–2016 accelerated the reform of EU asylum policies.

Asylum reforms include increased harmonization of rules and procedures across member states.

The EU has agreed on relocating asylum seekers between countries.

A new agency has been established to strengthen control of the EU’s external border.

The EU has expanded its commitment to resettling refugees directly from origin regions.

Cons

New policies do not fully address the weaknesses exposed in the 2015–2016 crisis.

Increased policy harmonization has not evened out the migrant “burden” between countries.

Relocation of asylum seekers has fallen short of modest targets.

Improved border controls have not succeeded in stemming the flow of irregular migrants.

Very modest progress has been made in shifting from a regime of spontaneous asylum-seeking to one of resettling refugees directly from origin regions.

Author's main message

The European asylum system suffers from weaknesses that were dramatically exposed during the migration crisis of 2015–2016. Border controls were unable to stem the flow of migrants and asylum applications fell very unevenly among EU member states. Reforms introduced in the wake of the crisis strengthen the existing system in some respects, but go only a small way toward creating a better system which would select those most in need of protection for direct resettlement without having to run the gauntlet of irregular migration and possible rejection.

Motivation

The European migration crisis of 2015–2016 was a major shock to the Common European Asylum System, which has been developed over the last two decades. It divided public opinion and prompted a stream of reforms to strengthen existing structures, to further unify the system across member states, and to introduce some new initiatives. This article outlines some of the key characteristics of the system as it existed before the crisis and then how it was put under extreme pressure during the crisis. It then considers how the crisis affected public support for the asylum system and how subsequent reforms responded to it. Conclusions drawn indicate that while the reforms go some way toward addressing the inherent weaknesses of the system they fall far short of replacing spontaneous asylum-seeking with a program of resettling refugees directly from countries of first asylum.

Discussion of pros and cons

Background to the existing policy regime

The foundation of existing asylum policies is the 1951 Refugee Convention. It was conceived in the wake of mass displacements in Europe after the Second World War and it was shaped by the geopolitics of the day. In the Convention, a refugee is defined as a person who is outside their country of origin and, who has a “well-founded fear of persecution” within that country (the full text can be found here: https://www.unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html). A country that is signatory to the Convention has a duty to provide access to a process to determine if the individual applicant qualifies as a refugee, and if so, to provide protection. Also, an applicant who is on the territory or at the border must not be returned to a situation where their life or freedom would be threatened (non-refoulement). Unauthorized arrival does not prejudice either access to the procedure or the outcome of the procedure. In principle, there is no limit to the number of applicants that a state must process and potentially accept as refugees.

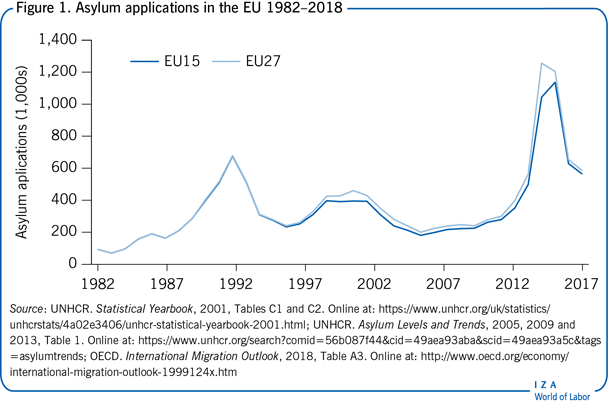

Because the Refugee Convention was conceived in circumstances very different from those that later emerged, it left open to destination countries a range of measures that could deter or divert potential asylum-seekers. Figure 1 shows first instance asylum applications in EU countries. The number of “spontaneous” asylum seekers—those arriving on their own initiative and not part of an organized resettlement program—increased steeply from the mid-1980s to a peak in 1992. This led to a sharp tightening of asylum policies that included enhanced border protection (to block access to asylum procedures), tougher screening of asylum applications received, and greater constraints placed on asylum seekers during processing (keeping track of them and limiting their rights to welfare benefits) [1]. One landmark policy change took place when Germany (the most popular EU destination) reformed its Basic Law so that the claims of those from a “safe country of origin” or those who passed through a “safe third country” would be treated as “manifestly unfounded.”

In the wake of this round of tightening and a second wave in the late 1990s the EU established its Common European Asylum System (CEAS). This involved the harmonization of the policies of individual member states with respect to the definition of a refugee, processing procedures, and reception conditions for asylum seekers. Two rounds of directives, one in the mid-2000s and another in the following decade, sought to prevent a race to the bottom in asylum policies that aimed to deflect or deter potential applicants. Broadly speaking, the CEAS attempted to strike a balance between excluding economic migrants while protecting the rights of genuine refugees. These policies came under extreme pressure in the migration crisis of 2015–2016 when, as Figure 1 shows, the number of asylum applications in the EU increased to over a million per year.

Criticisms of European asylum policies before the crisis

Asylum policy has long been contested terrain between those who favor tougher policies and those who advocate greater generosity toward refugees. This debate covers a broad range of topics, with three key issues discussed here. The first is that over the three decades before the migration crisis only about 40% of asylum seekers were recognized as meeting the definition of a refugee. Those whose applications were rejected were legally required to leave the country, though many disappeared into the informal economy. Statistics such as these fed the belief that most asylum seekers were economic migrants rather than genuine refugees. Such migrants applied for asylum because they had no access to other immigration channels (such as employment or family reunification). By applying for asylum they gained admission to the chosen destination and the opportunity to abscond if their claim was rejected. In response most countries increased their control over applicants while their claims were being adjudicated (e.g. by dispersing them to reception centers) and redoubled their efforts to deport a larger share of failed asylum applicants.

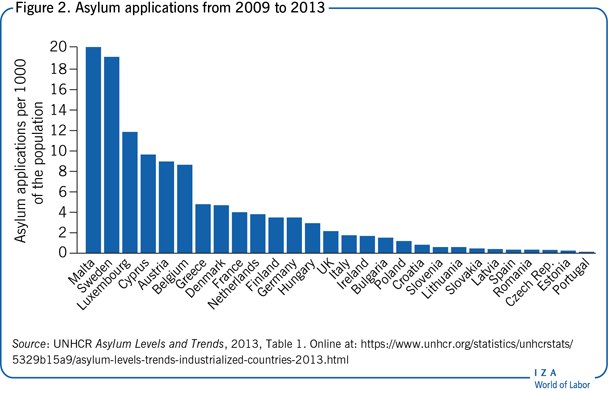

The second issue is that the so-called refugee burden was very unevenly distributed among EU countries. In the pre-crisis years 2009–2013, Germany received the largest number of applications, followed by France, Sweden, and the UK. But as Figure 2 shows, the countries with the largest numbers per capita of the population were Malta, Sweden, and Luxembourg, followed by Cyprus, Austria, and Belgium. The policies under the CEAS exacerbated (or at least failed to relieve) this imbalance in two ways. First, closer harmonization of policies meant, at least in principle, that the “relative price” (policy toughness) of gaining refugee status did not respond to relative demand so, at the margin, asylum seekers were not diverted to less desirable destinations [2]. Second, the EU's Dublin Regulation (aimed at preventing “asylum shopping”) means that an asylum applicant can apply to only one EU country, normally the country of first entry. This has tended to concentrate asylum applications in some countries on the EU's external border, notably Malta, Cyprus, Greece, and Italy. Back in the 1990s it was proposed that the EU should adopt a mechanism to even out the responsibility for refugees by reallocating some of them from countries with higher numbers of refugees to those with fewer. At the time this was strongly resisted and, while it sometimes resurfaced, for two decades no progress was made.

A third issue is control of the EU's external border, aimed at preventing unauthorized entry. In 2006 the EU established Frontex, an agency intended to help member states implement common border control rules and assist in border management. The numbers crossing through different routes varied with changing conditions, depending most of all on cooperation with transit countries. A good example is the “friendship agreement” of 2008 between Italy and Libya which collapsed with the demise of the Gaddafi regime in 2011. This increased unauthorized migration through the Central Mediterranean route between 2010 and 2012 by a factor of three [3]. In the Mediterranean, there was a sequence of search and rescue operations, culminating in operation Mare Nostrum (2013–2014), which, by rescuing migrants from drowning, encouraged even more to risk their lives making the attempt. From 2014 this was superseded by operation Triton, which focused more on border protection.

It is worth stressing that there are widely differing views about the weaknesses of the European asylum system as it existed prior to the crisis. Refugee advocates argue that tougher asylum policies were excluding many deserving applicants and that, even under the CEAS directives, policy failed to accord refugees their full rights and often failed to protect vulnerable groups such as unaccompanied minors. Moreover, procedures still differed between EU countries and so the prospect of gaining recognition as a refugee was something of a lottery. Worse still, too little effort was being put into rescuing people in the Mediterranean and this was putting lives at risk

The migration crisis of 2015–2016

The root causes of the migration crisis are well known and are not the focus of this article. Suffice it to say that in the wake of the Arab Spring and the civil war in Syria large numbers of those displaced started arriving in Europe—a rather different pattern to that of the early 1990s [4]. The EU's border agency, Frontex, estimates that the number of unauthorized crossings on different routes across the Mediterranean, the Western Balkans, and Greece–Albania was about 10,000 per year from 2009 to 2013 before rising to 1.82 million in 2015 and half a million in 2016. In 2015, among those whose origin could be determined (about two-thirds of the total), about half were from Syria, mostly via Turkey, and there were also substantial numbers from Afghanistan and Iraq. The main entry points to the EU were Greece, Italy, Malta, Hungary, Croatia/Slovenia, and Bulgaria. Of the migrants surveyed on arrival via the Central and Eastern Mediterranean (Aegean) in 2015 and 2016, more than three-quarters reported that they were fleeing persecution [5].

The response to this crisis was to introduce border closures, first between Turkey and Greece followed shortly after by the borders between Serbia and Hungary and between Turkey and Bulgaria. In August 2015 the German government, led by Angela Merkel, proclaimed that it would welcome migrants from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, which acted as a strong stimulus to further arrivals. According to Frontex, unauthorized border crossings on the Western Balkan route increased from 34,559 in the second quarter of 2015 to 229,746 in the third quarter. Under the pressure of increasing numbers of migrants determined to reach interior destinations such as Germany and Sweden, the operation of the Dublin system was ignored in Mediterranean countries and, following Chancellor Merkel's welcome announcement, it broke down completely. Countries on the EU's southern and eastern borders, notably Greece, essentially became transit countries, often neglecting even to register migrants traveling through. This had knock-on effects of re-establishing border controls in countries further north, such as Belgium, Denmark, and Sweden. Border controls shifted inwards as the system unraveled and six out of the 22 Schengen members had re-introduced border controls by March 2016.

From April 2015 hotspots were established in Greece and Italy where migrants could have their claims assessed and then be either relocated within Europe, if successful, or repatriated, if not. And in September that year a scheme was agreed (against heated opposition) to relocate 120,000 refugees to other EU countries. But this gained little traction and in 2016 Germany started to backtrack on its open door policy while Sweden also rowed back on its previously liberal policies. Thus, large numbers remained stranded in southern Europe. The agreement struck between the EU and Turkey in March 2016 stemmed the inflow. This provided that irregular migrants crossing the Aegean who were not recognized as refugees would be returned to Turkey. For every Syrian returned to Turkey, another Syrian would be resettled in the EU directly from Turkey. Together with enhanced border controls, the effect was to drastically reduce the number of migrants through this route by more than 90% between the first and second quarters of 2016. This put an end to the immediate crisis, although sustained flows continued on other routes.

Public opinion and politics

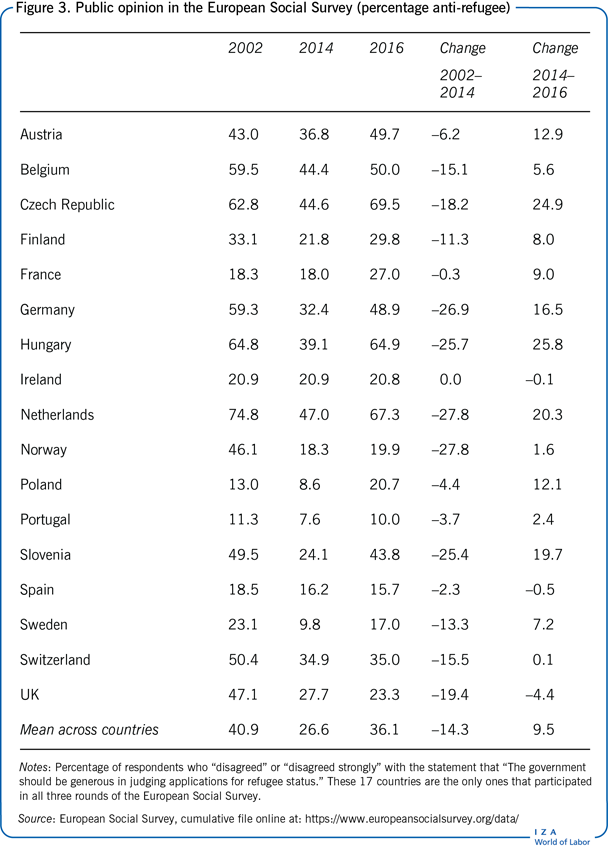

It is widely believed that the migration crisis caused a political backlash, not least in Germany in response to Chancellor Merkel's original gesture of welcome. The success of far-right parties in elections across Europe and the outcome of the Brexit referendum have been attributed in part to the migration crisis. In framing their agendas, political leaders must pay heed to those that elect them, so it is worth examining public opinion trends in more detail. In 2002, 2014, and 2016 the European Social Survey asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed that their country's government “should be generous judging applications for refugee status.” Figure 3 reports the percentage that disagreed with the statement. Two features stand out: first, in 2014, on the eve of the crisis, in each of the 17 countries surveyed, less than half of the respondents expressed anti-refugee sentiment and the country average was just over a quarter. The second feature is that opinion became progressively less negative from 2002 to 2014 in almost every country, but that trend was reversed between 2014 and 2016. It is notable that Germany and Austria, as well as some of those on the EU's eastern border, were among the countries with the greatest reversals.

Even during the crisis, in 2016, anti-refugee opinion was in the minority in most countries, but two other features contributed to the backlash. First, opinion is very negative about illegal or unauthorized immigration as compared with legal immigration, and this was a key feature of the migration crisis [1]. Second, the salience of migration as an issue increased. In its biannual public opinion survey Eurobarometer asks respondents to state what they think are the two most important issues facing their country. From 2004 to 2012 on average about 10% of respondents in EU countries chose immigration as one of their top two issues. By November 2015, however, the country average had increased to 30%, reaching as high as 75% in Germany, up from 35% a year earlier. The combination of broadly negative opinion about migration and high salience is likely to be reflected at the ballot box in the form of support for right-wing populist parties.

The evidence indicates that on balance a migrant influx increases support for populist parties. In Austria, votes for the far-right Freedom Party from 1979 to 2013 are causally related to the increase in immigration [6]. And across Europe, votes for nationalist parties in European elections are influenced by the local share of unskilled immigrants, especially those from outside Europe [7]. In Germany, the political backlash following the migration crisis is reflected in increased support for Alternative für Deutschland, which gained representation in the German Bundestag for the first time in the 2017 federal election, winning 94 of the 709 seats. On the Greek islands, exposure to migrant arrivals enhanced support for exclusionary practices and increased voting for the far-right party, Golden Dawn [8]. However, it is unclear how support for the far-right translates into more restrictive asylum policies. On the one hand, EU-level asylum policies under the CEAS are one step removed from national governments. On the other hand, even when such parties fail to get elected into government they often shift the agendas of mainstream parties.

Limitations and gaps

There are practical limitations on what the EU can do when it comes to migration and asylum reform. First, there is overwhelming evidence that the number of asylum applications is driven by civil war and human rights abuse in countries that are typically also poor [1], and so separating genuine refugees from economic migrants is inevitably somewhat arbitrary. The vagaries of these conditions also mean that major surges in asylum applications such as those observed in the early 1990s or in 2015–2016 are likely to recur.

Second, worldwide there are 26 million refugees and another 41 million internally displaced people. While it is sometimes argued that increased assistance to origin and transit countries could reduce the incentive to seek asylum in the West, even a vast increase in development aid could have only marginal effects on this sum of human misery. Instead the EU must find ways of targeting its asylum policy toward those in the most desperate need.

Summary and policy advice

Policy developments during the recent migrant crisis included a mixture of emergency measures and longer-term reforms [9]. Although some after-effects of the crisis persist, such as the concentration of migrants in Greek and Italian hotspots and some emergency border controls, in other respects the European asylum system has reverted to the previously existing state of affairs. For instance, the 2015 agreement on relocating asylum seekers in order to even out pressures on individual nations has stalled. On the other hand, the EU has proceeded with a third round of policy harmonization with the aim of strengthening protection for asylum seekers and imposing greater uniformity in rules and procedures in different member states. However, as with the previous iterations these policies are unlikely to promote a more equitable distribution between countries. And although the revised Dublin Regulation includes an element of relocation during times of crisis, it is doubtful that this mechanism would withstand pressures on par with those of 2015–2016, which led to its de facto suspension [10].

Medium-term priorities should be to strengthen border controls and measures for temporary protection. In 2016 the EU replaced Frontex, which was seen as ineffective in the crisis, with the European Border and Coastguard Agency, armed with executive power and a larger budget. This agency provides stronger border protection, especially for weak points on the EU's external border where national capacity was limited. This is one step in reducing unauthorized border crossings, but, given the non-refoulement obligation, it is most effective when operated in cooperation with transit countries. A second priority is providing temporary protection in times of crisis. The EU's Temporary Protection Directive of 2001, providing for emergency redistribution, was not even activated in the 2015–2016 crisis [11]. It should be strengthened and augmented with a better mechanism for activation. To gain support, it should also be underpinned by greater financial resources. The Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund was allocated a total €3,137 million from 2014–2020, but this only amounts to 0.29% of the EU budget.

A more fundamental long-term priority is to shift away from spontaneous asylum seeking to a comprehensive resettlement program. As part of the package of measures launched in 2016 the EU increased its commitment to an expanded resettlement program from around 5,000 per year in the pre-crisis years to 20,000. In this program, vulnerable refugees are transferred directly to the EU, without having to resort to smuggling networks and taking risky routes to gain unauthorized entry. To some degree these policies build on the landmark agreement between the EU and Turkey, which combines tighter border control with an element of resettlement. But it is only a small step toward shifting away from a system of spontaneous asylum seeking, which provides incentives for migrants to take risky passages only for the majority to have their claims ultimately rejected.

The EU should shift more radically toward resettlement along the lines of the Australian/Canadian/US programs, which would have several advantages over the existing system. First, it would target those most in need of protection from persecution rather than selecting those with the initiative and wherewithal to migrate. Second, it would reduce the challenge posed by rejected asylum applicants. And third, it would be more consistent with public opinion, which is positive about genuine refugees, skeptical about economic migrants, and strongly opposed to unauthorized immigration [1]. While such a policy shift would mitigate the type of backlash observed during the recent migrant crisis, it is hard to imagine that significant progress can be made while spontaneous asylum applications are still running at half a million per year.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used extensively in all major parts of this article [1].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Tim Hatton