Elevator pitch

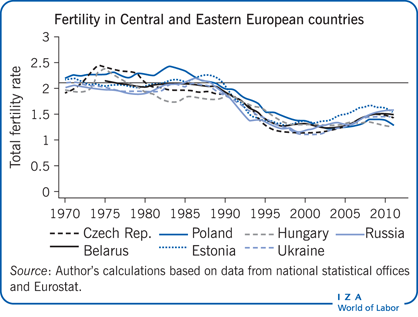

Since 1989 fertility and family formation have declined sharply in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Fertility rates are converging on—and sometimes falling below—rates in Western Europe, most of which are below replacement levels. Concerned about a shrinking and aging population and strains on pension systems, governments are using incentives to encourage people to have more children. These policies seem only modestly effective in countering the impacts of widespread social changes, including new work opportunities for women and stronger incentives to invest in education.

Key findings

Pros

In Central and Eastern Europe, fertility rates are now below population replacement rates.

Countries are also seeing later marriage and childbearing and rising numbers of children born to single women.

Policies encouraging births can modestly increase the number of births, particularly of second and third children.

To stem population loss due to declining fertility, pronatalist policies combined with increased immigration is likely the most effective approach.

Cons

Recent declines in fertility could reflect postponed childbearing rather than a decline in the average number of children borne per woman.

Until the women of childbearing age in the 1990s reach the end of their childbearing years, the precise extent of the fertility decline cannot be known.

Policies encouraging births are unlikely to fully counteract economic and social changes that lead to fertility rates below replacement level.

There is no clear evidence for policymakers on what policies are most likely to raise fertility rates at the lowest budgetary cost.