Elevator pitch

Rising life expectancy and the growing fiscal insolvency of public pension systems have prompted many developed countries to raise the pension entitlement age. The success of such policies depends on the responsiveness of individuals to such changes. Retirement has increasingly become a decision made jointly by a couple rather than individually by one partner. The empirical evidence indicates that almost a third of dual-earner couples in Europe and the US coordinate their retirement decision despite age differences between partners. This joint determination of retirement has important implications for policies intended to reduce the burden of pension costs.

Key findings

Pros

Risks of insolvency of public pensions systems have prompted several governments to adopt measures to raise official retirement ages.

Nearly a third of dual-earner couples in Europe and the US coordinate their retirement, independently of the age difference between spouses.

The rising participation of women in the labor market increases the fiscal impact of the phenomenon of joint retirement.

A preference for shared leisure may increase the probability of partners retiring close in time.

Early labor market exits by women whose husbands have retired may increase inequality and reduce economic well-being among the elderly.

Cons

Raising the official retirement age may not reduce the fiscal burden if one spouse’s retirement encourages the other spouse to retire early.

Raising the statutory retirement age has a positive direct effect on female participation but a negative indirect effect on women who leave the labor market together with their husbands.

In some developed countries, gender differences in official retirement ages still persist.

One spouse may leave the labor market to take care of a sick partner or may postpone retirement to cope with increased medical expenses in old age.

Author's main message

Empirical studies suggest that couples in Europe and the US are increasingly coordinating their retirement decisions. Decisions concerning joint retirement are viewed as the outcome of a bargaining process between spouses involving several factors, such as incentives in the pension system, each spouse’s levels of income and wealth, preference for shared leisure, health status, and potential care-giving roles. To avoid biasing efforts to estimate the expected impact of any pensions reform, policymakers should consider this joint decision-making behavior.

Motivation

An aging population presents major challenges to public pension systems in developed countries. Unless people work longer as they live longer, public pension systems will become unsustainable and pension payments cannot be guaranteed. The implications of rising life expectancy for the financial stability of public pension systems have led some governments to raise the official eligibility age. However, the success of such policies depends on how individuals respond to the incentives built into the systems.

Most studies on what influences people’s retirement decisions note that people react to changes in the eligibility requirements for their own pension. For example, among the many studies on the importance of pension system incentives, international comparative studies find a strong negative correlation for older workers between the generosity of the anticipated pension scheme and the likelihood of working longer [1], [2]. Nearly all studies, however, consider retirement as an individual decision and examine only the decisions of men.

In reality, the majority of European and US households whose heads are approaching retirement are dual-earner households. Estimates of the impact of regulatory changes in public pension systems should therefore incorporate not only the direct effect on individual decisions but also the indirect or spillover effects of those decisions on other members of the household, in particular on spouses.

This paper reviews recent evidence on how responsive each member of a couple is to individual retirement eligibility criteria, as well as to a partner’s retirement choice. Empirical studies suggest that couples coordinate their retirement decisions and that failing to consider this joint behavior in estimating the impact of policies that change the statutory retirement age may bias the results.

Discussion of pros and cons

Labor market participation rates for older workers and official and effective retirement ages

As populations age, people are increasingly being encouraged to extend their working life to reduce the strain of public pension systems on national budgets. While many features of the pension systems in developed countries vary, countries have recently introduced some common policy proposals to reduce the financial burden of public pension systems. These measures include raising the official pension eligibility age, tightening contribution requirements, and promoting the development of supplementary private pension schemes.

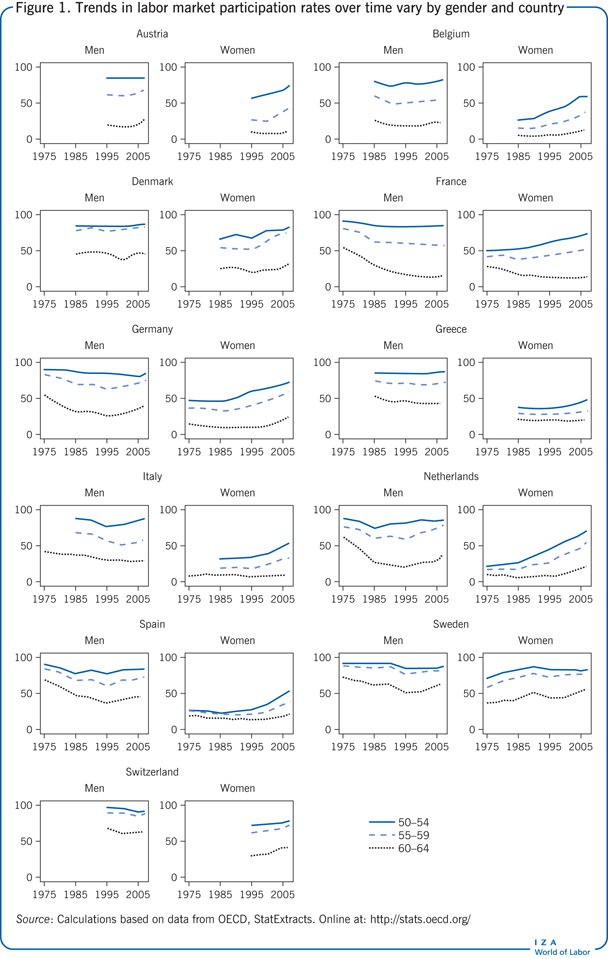

The share of individuals who participate in the labor market after the age of 50 varies considerably across developed countries, ranging from less than 50% in countries like Austria, Italy, and Spain, to more than 70% in Sweden and Switzerland. These differences are even more pronounced for women, with the average female participation rate ranging from only 30% in Greece to 71% in Sweden. Underlying these cross-country differences in the labor participation rates of older workers are very different trends for different countries (Figure 1). In several European countries, labor market participation rates for older men have fallen substantially since the 1970s, while participation rates for older women have been rising in most of these countries.

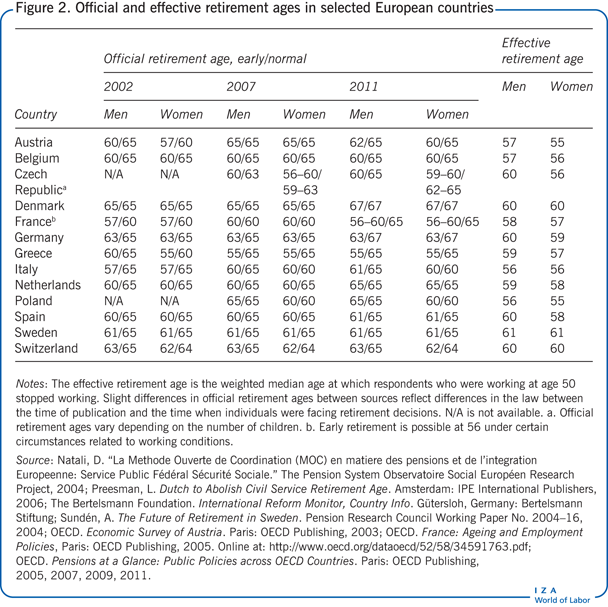

Closely related to the labor market participation rates of older workers is the effective age of retirement—that is, the actual age at which individuals who were working at age 50 stopped working. In most countries, the effective age of retirement is considerably below the official age of retirement, and women are found to retire approximately one to two years earlier than men. In Europe, the official retirement age varies by country by as much as 10 years: for example, the official early retirement age ranges from 55 in Greece to 65 in Denmark (Figure 2). There are also some large differences in retirement age by gender, especially for countries like Austria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, Poland, and Switzerland.

Joint determination of retirement by married couples

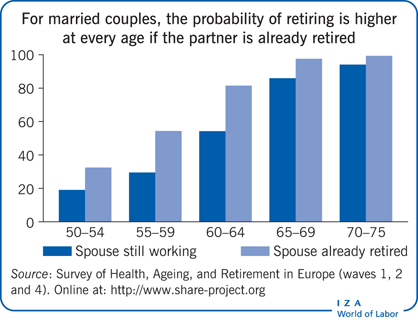

Apart from the statutory retirement age, there are many other reasons why older people may not work, such as bad health and family responsibilities, which can affect older men and women differently. And, as more and more women join the labor force, the typical family approaching retirement in a developed country is now a dual-earner family. Thus, retirement has become a decision that depends not only on the situation and conditions facing an individual but also on the specific situation of an individual’s spouse. There is ample empirical evidence showing that a substantial fraction of couples coordinate their retirement decision, irrespective of the age difference between them, and that the later-retiring spouse tends to leave the labor market as quickly as possible after the partner’s retirement. This phenomenon, which accounts for nearly a third of retirement patterns in Europe and the US, is known as joint retirement and has received considerable attention in the economics literature since the 1990s ([3], [4], [5], [6], among others).

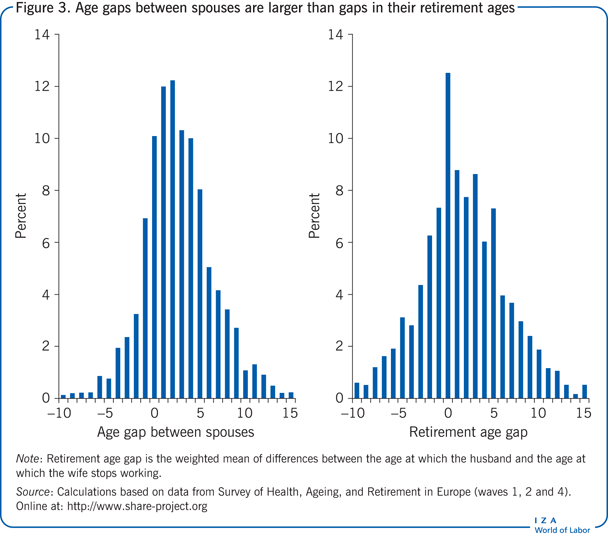

The extent of this phenomenon among European couples can be illustrated using data from waves 1, 2, and 4 of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). The left graph in Figure 3 is a histogram of the age differences between spouses. The average gap between the husband’s age and the wife’s age is 2.2 years. This age difference remains similar across SHARE countries (with the exception of Greece, where the average age gap is 4.4 years). The right graph in Figure 3 is a histogram of the differences between the age at which the husband left the labor market and the age at which the wife left the labor market. As predicted by the joint retirement hypothesis, the peak at zero is large and substantially higher than the proportion of couples with zero age difference between spouses. In the US, around 30–40% of couples exit the labor force within one year of each other, according to data from the Retirement History Survey [4], the New Beneficiary Survey [3], and the Health and Retirement Survey [5].

In general, the retirement decisions made jointly by a couple depend on the institutional rules of the pension system, as well as characteristics of the spouses, such as their age, health, education, and household composition. Several theoretical models suggest an interdependence of the retirement decisions of couples. In a unitary model, the income or the retirement benefits of the spouse affect the wealth level of the household as well as the demand for leisure. Similarly, a preference for shared leisure between spouses may increase the probability of one spouse’s retiring soon after the first spouse retires regardless of whether this is due to complementarities in leisure or to the selection of marriage partners with similar preferences for leisure. There are also health status and care-giving reasons that may motivate one spouse to leave the labor market to take care of sick relatives or to postpone retirement to cope with increased medical expenses. Several structural models emphasize that decisions concerning joint retirement are the outcome of a bargaining process between spouses.

Causal impact on one spouse of a change in retirement incentives for the other spouse

The reduced-form models surveyed in this paper take a step back and concentrate on the causal estimation of the impact that a change in one spouse’s retirement incentives may have on the other spouse’s retirement behavior. Although these models do not identify the mechanisms through which this process operates, they are able to quantify both the direct effect on retirement behavior due to changes in an individual’s own pension incentives and the indirect effect due to changes in a spouse’s retirement incentives. The critical challenge for policy making then is to measure spillover effects between spouses that represent genuine retirement incentives associated with the age component of the institutional retirement rules and that do not include differences in taste or preferences, which may arise as a result of marriages between individuals with similar unobserved tastes.

One way to identify the indirect effects of changes in a spouse’s retirement incentives on the other partner is to analyze episodes related to large institutional changes in retirement incentives, such as a change in the official normal and early retirement ages. Since the statutory retirement age is an institutional feature, it is not correlated with either spouse’s retirement preferences. This approach looks at people who are just slightly above the legal retirement age and those who are just slightly below it. These people are likely to be very similar in all aspects other than in the way they are affected by the legal retirement age. Because individuals cannot manipulate their age, this approach is similar to a randomized controlled experiment. One study uses the institutional variation across the UK and the US to analyze husbands’ responses to their wives’ retirement incentives [7]. In the UK, the statutory retirement age in 2010 was 60 for women and 65 for men, while in the US both men and women are eligible to receive social security early retirement benefits at age 62. Similarly, studies for Europe are able to take advantage of the variation in the official normal and early retirement ages across countries, as reported in Figure 2 [8].

Instead of a multi-country comparison, one study uses the discontinuity in individual retirement probability at the legal early retirement age in France induced by a 1993 policy change that increased the number of years of pension system contributions necessary to retire with a full pension for younger cohorts [9].

Another alternative that can mimic an experimental design is a difference-in-difference approach that compares changes in the retirement decisions of spouses before and after a pension reform that alters the entitlement age for different subgroups. In this approach, the change in behavior of the treatment group (affected by the reform) is compared with the change in behavior of a control group (unaffected by the policy changes). An example is the allowance for dependent spouses introduced in 1975 to the Canadian Income Security System, which targeted women in poor families [10]. Similarly, a 2001 reform in Sweden that increased work incentives differently across birth cohorts has been used to identify spillover effects of a change in the spouse’s pension incentives on an individual’s own pension behavior [11]. Finally, a 1993 reform in Australia increased the eligibility age for pension benefit payments for women only [12].

Differential impacts by gender

In terms of the estimated magnitude of both the direct and the indirect effect of changes in the official retirement age, this strand of the literature has reached consensus on findings of significant spillover effects, although with some asymmetries by gender. In the case of couples in Europe, being above the official early retirement age increases the probability of retirement by six percentage points for men, while the direct effect is not significantly different from zero for women [8]. For the official normal retirement age, the estimated direct effect is larger and highly significant, at 24 percentage points for men and 18 percentage points for women.

The indirect effects of changes in the official retirement age on the other spouse are also large in studies that allow for the retirement of one spouse to effect the retirement decision of the other spouse. Estimates show that wives whose husbands have retired are 21 percentage points more likely to retire themselves. Since women are typically younger than their husbands, these women’s “premature” exits from the labor market have important policy implications, as they can lead to inequality in economic well-being among the elderly. Women typically have a less continuous work history than men do, resulting in lower retirement pensions, an effect that is exacerbated by women’s longer life expectancies than men. For men, the indirect effect of a wife’s decision to retire is generally economically positive but not significantly different from zero. However, considering the small sample sizes usually available in the SHARE data, it is possible that the finding of statistical insignificance for the estimated indirect effect for men is due mainly to a lack of precision in the analysis because of the small sample size.

Indeed, studies using data sets at the national level find significant results for men as well. A study of the 1993 Age Pension reform in Australia, which raised the eligibility age for women only and had a significant direct effect on women’s retirement age, led to an increase in the labor force participation of the husbands of women in the affected cohorts [12]. A UK study that examined the effect of a lowering of the pension eligibility age of women found that British men are 14–20 percentage points more likely to retire when their wife reaches the official eligibility age than are their US counterparts (there was no change in the retirement age for women in the US) [7].

For France, based on data from French Labor Force Surveys over 1990–2002, there is also evidence that an increase in the length of required pension contributions has indirect effects on couples in the labor market, in addition to large and statically significant direct effects on the probability of retirement [9]. In particular, French married men whose wives have reached early retirement age are more likely to retire, but the reverse is not true for married women. However, married women’s hours of work fall by one hour per week if their spouses retire; the reduction is even larger for married men, who work two hours less per week when their wives retire. And in Sweden, a study suggests that ignoring the impact of spousal spillover effects underestimates the impact of the pension reform by as much as 14% [11].

Limitations and gaps

The evidence reviewed in this article is limited to the body of literature that examines interactions between spouses by identifying causal effects. These studies all exploit some exogenous variation in the legal retirement age of at least a subgroup of the population. An alternative approach is to estimate more complex models of the full characterization of couples’ retirement decisions [8]. Although those structural models are an attractive approach when the objective is to obtain parameters that summarize the behavior of couples, such models require fully and carefully specifying financial and stochastic (random) environments, a major drawback [7].

This paper also ignores alternative exit routes out of the labor force such as disability and unemployment, along with their unintended spousal spillover effects. The evidence on the so-called added worker effect—the wife’s labor market response to her husband’s becoming unemployed—is mixed, with some studies finding a positive, but small, effect, and others finding no effect or a negative effect. The evidence on the relationship between spousal retirement and absence from work because of illness is almost nonexistent. Recent research with exceptionally rich register data in Norway and Sweden finds that a husband’s retirement significantly increases his wife average long-term absence for sickness or the probability that the wife will receive a disability pension.

Finally, although the literature reviewed in this article is silent on the mechanisms behind joint retirement patterns, there are some empirical studies in progress that are trying to look more deeply into those aspects. For instance, a study in France is investigating the extent to which partners actually do spend more leisure time together in retirement, exploiting same-day diary data collected for both partners. The study finds that the immediate increase in the joint leisure hours of partners after the wife retires—the wife is usually the last to retire in dual-earner couples—is smaller than the increase in the husband’s separate leisure hours that follow the husband’s retirement.

Summary and policy advice

Given the empirical evidence on the importance of spillover effects in the retirement decisions of couples, a note of caution is in order concerning the formulation of policy advice. If one of the priorities for structural and governance reforms in the euro area is to encourage people to work longer by raising the legal retirement age, policymakers need to take into account the indirect effects of one spouse’s retirement decision on the labor market participation of the other spouse. It is not enough to consider only the positive effect of a higher legal retirement age on the labor market participation of individuals who are directly affected by the change. The indirect effects indicate that a husband’s retirement may reinforce the probability of his wife’s leaving the labor market in the case of a policy that lowers the pension eligibility age of women, and vice versa.

Similarly, understanding the joint retirement decisions of couples should be relevant for policymakers in countries where gender differences in the official retirement age persist and where the desire is to equalize the official retirement age for men and women. In the UK, for instance, the official pension eligibility age was 65 for men and 60 for women for many years. But beginning in 2020, the official retirement age will be 66 for both men and women. This change is expected to affect women’s retirement decisions more than those of men, but it could change men’s retirement decisions more than expected as well.

Overall, the evidence presented in this paper suggests that a relevant factor for the individual decision to leave the labor market is the retirement decision made by the spouse—in other words, that some couples coordinate their decisions to retire. As such, policymakers should consider this factor when estimating the expected impact of any reform of the pension system. The rising participation of women in the labor market, and the influence of their husbands’ retirement decisions on women’s own retirement decisions in many countries, increase the quantitative importance of this phenomenon of joint retirement.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Gema Zamarro. The opinions and analyses are the responsibility of the author and, therefore, do not necessarily coincide with those of the Bank of Spain or the Eurosystem. All errors are the author’s own.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Laura Hospido