Elevator pitch

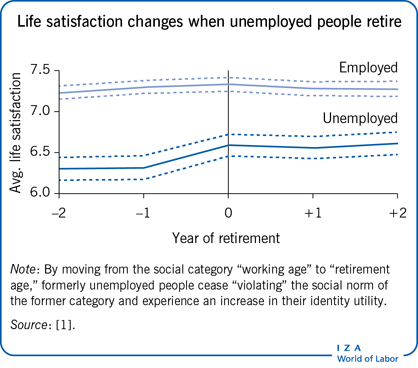

Unemployment not only causes material hardship but can also affect an individual's sense of identity (i.e. their perception of belonging to a specific social group) and, consequently, feelings of personal happiness and subjective well-being. Labor market policies designed to help the unemployed may not overcome their misery: wage subsidies can be stigmatizing, measures that require some work or attendance for training from those receiving benefits (workfare) may not provide the intended incentives, and a combination of an unregulated labor market and policy measures that bring people who became unemployed quickly back to work (flexicurity) may increase uncertainty. Policies aimed at bringing people back to work should thus take the subjective well-being of the affected persons more into consideration.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployment causes material hardship and threatens a person’s sense of social identity and self-worth, but barely reduces emotional well-being derived from day-to-day experiences.

Wage subsidies that bring people into work increase their well-being compared to unemployment, in particular if the long-term unemployed are targeted.

Workfare initiatives can effectively separate the voluntarily from the involuntarily unemployed without harming those who take them up.

A flexicurity system that helps unemployed people back to work significantly increases subjective well-being, as it allows people who re-enter the labor market to restore their identity.

Cons

Active labor market policy instruments, such as wage subsidies, could diminish subjective well-being, for example, through the stigma associated with receiving welfare transfers.

Workfare participants may consider workfare initiatives as less detrimental than being unemployed; workfare may thus not provide the intended incentives to look more intensively for a new job.

Although flexicurity may improve subjective well-being, it comes at the cost of higher job insecurity, which is not completely offset by higher employability.