Elevator pitch

Standard economic theory suggests that individuals know best how to make themselves happy. Thus, policies designed to encourage more forward-looking behaviors will only reduce people's happiness. Recently, however, economists have explored the role of impatience, especially difficulties with delaying gratification, in several important economic choices. There is strong evidence that some people have trouble following through on investments that best serve their long-term interests. These findings open the door to policies encouraging or requiring more patient behaviors, which would allow people to enjoy the eventual payoff from higher initial investment.

Key findings

Pros

Impatient people behave differently from patient people when making choices with implications for the labor market, including educational investment and job search.

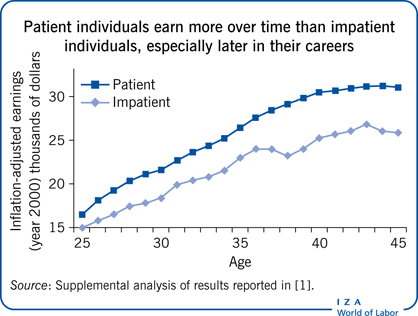

Post-schooling, impatient people earn substantially less than their patient counterparts, and the earnings gap grows throughout their careers.

Much of this behavior reflects “time-inconsistent” preferences, when preferred investment choices depend on how soon investment costs are paid.

Time-inconsistency can justify policy interventions designed to increase individuals’ investment.

Cons

Policies designed to increase investment are hard to justify if people’s choices are rational.

Time-inconsistency is difficult to measure directly, so policies are difficult to target appropriately.

The relationship between what economists call “preferences” and what psychologists call “personality” is still incompletely understood.

It can be hard to separate the direct effects of ongoing time-inconsistent choices from the effects of lower investment in cognitive skills earlier in life.