Elevator pitch

Standard economic theory suggests that individuals know best how to make themselves happy. Thus, policies designed to encourage more forward-looking behaviors will only reduce people's happiness. Recently, however, economists have explored the role of impatience, especially difficulties with delaying gratification, in several important economic choices. There is strong evidence that some people have trouble following through on investments that best serve their long-term interests. These findings open the door to policies encouraging or requiring more patient behaviors, which would allow people to enjoy the eventual payoff from higher initial investment.

Key findings

Pros

Impatient people behave differently from patient people when making choices with implications for the labor market, including educational investment and job search.

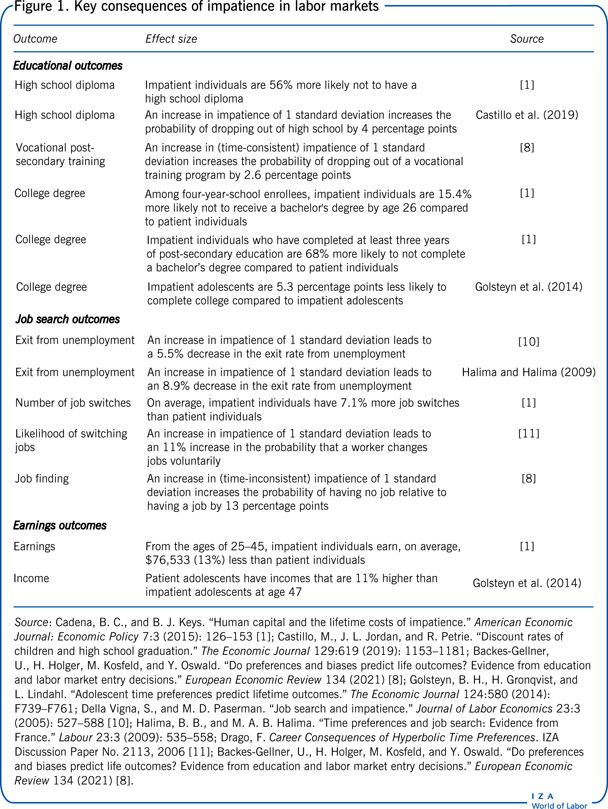

Post-schooling, impatient people earn substantially less than their patient counterparts, and the earnings gap grows throughout their careers.

Much of this behavior reflects “time-inconsistent” preferences, when preferred investment choices depend on how soon investment costs are paid.

Time-inconsistency can justify policy interventions designed to increase individuals’ investment.

Cons

Policies designed to increase investment are hard to justify if people’s choices are rational.

Time-inconsistency is difficult to measure directly, so policies are difficult to target appropriately.

The relationship between what economists call “preferences” and what psychologists call “personality” is still incompletely understood.

It can be hard to separate the direct effects of ongoing time-inconsistent choices from the effects of lower investment in cognitive skills earlier in life.

Author's main message

Economists tend to think that individuals know best how to spend their own resources. As a result, they view policies that are designed to change people's investment choices as paternalistic and are reluctant to propose them. Yet policies designed to encourage additional schooling or more job search effort can actually make people happier when the policies’ targets have difficulties with commitment. The empirical evidence suggests that patience can be learned and that a minority of individuals would be happier if they were incentivized or required to invest more for the future.

Motivation

When economists model choices that people make over time, a key component is the individual's level of “patience,” or the discount rate. This personal characteristic determines how much happiness (utility) a person is willing to give up today in order to increase future happiness. Many important economic decisions involve these kinds of intertemporal tradeoffs, including obtaining additional schooling and searching for a new job while unemployed. A key question that has emerged in recent research is whether individuals make these decisions in a “dynamically inconsistent” way: people acting this way repeatedly intend to make the patient choice in the future, only to succumb to temptation when faced with the immediacy of the costs. This article discusses recent evidence on the role of impatience in important investment choices affecting the labor market, with a particular focus on patterns that suggest dynamic inconsistency.

Discussion of pros and cons

Policy implications depend on the type of impatience

A classic study in personality psychology suggests that the ability to delay gratification strongly predicts children's future success across a variety of outcomes [2]. Although a more recent follow-up study concludes that this prediction is weaker than it originally seemed [3], a large body of empirical evidence suggests that differences in patience explain some key differences in people's behavior. Importantly, for policy purposes, it is essential to understand whether individual differences in preferences for consumption now versus later are “time-consistent,” or whether they reflect difficulties committing to choices that people initially want to make.

A famous example illustrates the principal distinction between the two types of impatience [4]. Consider the following pair of decisions. In situation A, a person must choose between one apple today and two apples tomorrow. In situation B, a person must choose between one apple one year from today and two apples one year and one day from today. An individual with time-consistent preferences will always choose either one apple earlier or two apples later because, in both cases, getting the second apple requires waiting an additional day. Someone who always chooses the single apple is considered less patient than someone who always chooses to wait for the two apples, but both decisions are time-consistent. In contrast, someone with dynamically inconsistent impatience would initially choose two apples in situation B, but would then, after a year's wait, give in to the temptation of the immediate gratification of the single apple when presented with situation A. These two types of preferences generate different predictions about how impatience will affect important decisions related to the labor market.

Implications of standard economic models of impatience

Standard economic theory assumes that people make investment decisions “rationally” in order to maximize their lifetime happiness. For example, teenagers choose whether to drop out of high school or to stay enrolled by weighing the future benefits of improved earnings against the costs of staying in school (such as forgone current earnings and academic effort). If two students face the same costs and benefits but one chooses to drop out and the other to continue schooling, the dropout would be considered less patient than the persistent student.

Under this interpretation, however, individual differences in patience are no more remarkable than individual differences in any other kind of preferences. Further, if people are making these decisions rationally, it is difficult to justify interventions that incentivize people to be more future-oriented. Even if programs manage to entice people to save more or get more schooling, they will likely decrease people's happiness relative to letting them make free choices.

Implications of dynamically inconsistent impatience

In contrast, more recent models of intertemporal choice predict the type of preference reversals discussed in the apple example above, where a person's preferred level of investment depends on whether the costs need to be paid immediately. There are a variety of ways of modeling this self-control problem, but many versions are centered on a conflict between two different “selves” with differing ideas of how best to spend their resources [5], [6]. The current self, who wants to enjoy life as much as possible in the present, would like to avoid effort and to consume as much as possible. The future self would rather save and invest now in order to enjoy life more in the future. This tension between the two selves leads to overconsumption today and underinvestment for the future relative to a person's initial intentions.

When people have these types of self-control problems, policies that encourage them to be more future-oriented or that help them commit to additional investment can actually improve lifetime happiness. Because of the stark contrast between the two types of models’ implied scope for policies to make people happier, much of the empirical literature has concentrated on determining whether time-inconsistent impatience rather than standard impatience affects labor market outcomes. Research has found substantial evidence that people suffer from commitment problems related to time-inconsistency when making important choices that affect their entire labor market experience.

Identifying impatient individuals

A key challenge in this type of research is identifying impatient people in standard data sets. Measuring dynamic inconsistency directly is especially difficult. A common type of survey question asks individuals to consider a hypothetical choice between a smaller payment today and a larger payment in the future. These questions are often designed to determine the smallest future payment the survey respondent would accept in order to give up the payment today. Individuals who require large compensation in order to give up a payment today are deemed more impatient.

In addition to being somewhat complex, this measurement has the drawback of conflating standard impatience with dynamically inconsistent impatience. It is not clear whether requiring a large payment to wait reflects a self-control problem or a strong preference for money now. To distinguish these two possibilities, researchers must ask questions analogous to the apple example above. They must present individuals with an additional hypothetical choice between receiving money a short time in the future or a longer time in the future while keeping all the other details the same, including the length of time between the early and the late payments [7]. Individuals with time-inconsistent preferences require a larger sum to forgo payment “right now” than they demand to wait the same length of time between two future dates. However, even this well-reasoned measure is subject to concerns that respondents may worry that any promised future payment may be less likely to arrive than the one offered “right now,” which clouds the interpretation of these responses somewhat. With notable exceptions [7], [8], very few studies have access to this type of measure to characterize individuals’ impatience.

Instead, multiple studies have relied on a surprisingly powerful measure of impatience: interviewer ratings that were not originally designed to measure how people approach intertemporal choices. In many surveys with a live enumerator, the interviewer is asked at the conclusion of the survey to rate the respondent's demeanor during the interview. Typical choices include friendly/interested, cooperative, impatient/restless/bored, and hostile. Several studies have found that survey respondents rated as “impatient” based on this brief interaction with their interviewer behave in ways consistent with a difficulty with delaying gratification (e.g. [1], [8]). The roughly 10–15% of individuals coded this way are more likely to smoke, less likely to have a bank account, more likely to drink to the point of a hangover, and more likely to leave military service prior to the end of their initial commitments [1]. While these behaviors could reflect either time-consistent or time-inconsistent impatience, additional evidence from schooling choices and job search behavior supports a time-inconsistent interpretation.

Evidence of impatience in educational choices

Deciding how much schooling to get affects the entirety of a person's working career. This section, therefore, discusses how impatience affects multiple important educational choices.

High school completion

One clever study takes advantage of policies that change the minimum age at which students can legally drop out of school to show how patience affects educational investment [9]. The study, which uses census data from Canada, the UK, and the US, finds that birth cohorts that are required to get additional schooling enjoy higher earnings, less unemployment, and better health later in life. Each of these benefits was expected—educational investment is known to provide future benefits in exchange for effort and forgone earnings while in school. The size of the estimated cumulative financial benefits of additional schooling are so large, however, that dropping out of school is difficult to reconcile with a time-consistent form of impatience. As supporting evidence of this interpretation, the study finds that the affected birth cohorts reported being happier, as measured by life satisfaction questions. Together, these results suggest that many dropouts leave school due to a time-inconsistent form of impatience.

Another study uses the interviewer rating method discussed above to provide additional evidence that time-inconsistent impatience affects the high school dropout decision [1]. The key result is that impatient individuals are 56% more likely to drop out of high school compared to patient individuals with similar characteristics. The study relies on panel data—the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1979—and takes advantage of the fact that students are asked about their educational goals and expectations in early adolescence. When the analysis is limited to individuals who report wanting and expecting to complete high school, it finds similar increases in dropout risk for the impatient. This set of results reinforces the interpretation that, for many students, the decision to drop out appears to be an inability to avoid temptation rather than a “rational” decision that maximizes lifetime happiness.

Post-secondary education

That same study then tracks individuals who complete high school to see how impatience affects investment in college [1]. The study is especially interested in “preference reversals,” which are the hallmark of dynamic inconsistency. When the analysis is limited to individuals who say they want to get a college degree, impatient individuals are 15–20% less likely to actually receive one. The same result is found when the analysis is limited to those who actually enroll in college, as opposed to simply stating their desire for at least an undergraduate degree.

Next, the study considers and rules out alternative interpretations of these differences [1]. Perhaps the impatient were more likely to experience negative financial shocks, were less informed about the difficulty of collegiate coursework, or were more likely to have mistaken beliefs about how much they would enjoy additional schooling. The study first addresses these concerns by showing that the impatient are no more likely to report dropping out due to financial or academic difficulties. It then presents a key finding: among students who successfully complete three years of post-secondary schooling, the impatient are 68% more likely to fail to finish their degree. Presumably, after having completed these years of college credit, individuals have figured out how qualified they are for schooling and how much they like it.

A natural concern with this type of measure is that those rated as impatient by their interviewer are more likely to be members of disadvantaged groups who face additional barriers to long-term investment (e.g. African Americans and children of less educated parents). However, even after adjusting for a rich set of family background characteristics, including gender, racial group, family income bracket, and parental education, those rated as impatient continue to be more likely to make these impatient choices.

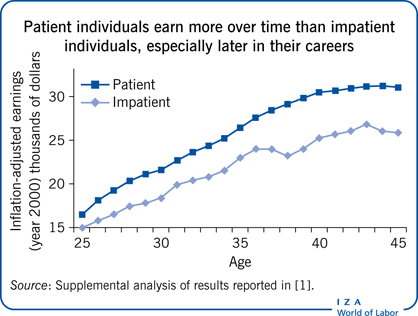

In addition to the studies discussed above, Figure 1 summarizes others that rely on different institutional contexts and different measures of impatience. Such variety in contexts and measures both corroborates and adds further nuance to the understanding of the role of impatience in educational completion decisions at all levels. Across these studies, the results reinforce the idea that time-inconsistent impatience leads to substantially lower educational completion rates.

Evidence of impatience in career paths

Job search while unemployed

After completing schooling, one of the primary ways of investing in future career growth is by changing jobs with the goal of building a career. Job search activity while unemployed presents a particularly intriguing context in which to examine the role of impatience in general and of time-inconsistency in particular.

Traditional job search theory describes individuals as making two important decisions in every time period (such as every week): how intensively to search for a job, and what wage or salary they are willing to accept to stop searching and start working, which is known as the “reservation wage.” Each decision requires making choices about how to trade off happiness in different time periods. An influential study shows that the two types of impatience—time-consistent and time-inconsistent—affect these two aspects differently [10]. Importantly, the two types of impatience lead to divergent predictions about differences in how much time patient and impatient workers will spend unemployed while looking for a new job.

In thinking about whether to accept a particular job offer, an individual considers whether to reject the offer and forgo earning that salary for a chance at a higher wage by continuing to search. A time-consistent impatient person will, therefore, set a lower reservation wage because they are less willing to wait for a better offer. Regardless of whether the job offer is accepted, the worker remains unemployed today, and income from a new job arrives only after starting work in the future. Dynamically inconsistent impatience should not affect decisions involving only future periods [6]. Therefore, any time-inconsistent impatience should have no effect on an individual's reservation wage.

The other important choice in job search is how hard to look for a new job. Search effort is costly because it requires forgoing leisure (“free time”) today in order to increase the likelihood of finding employment and, thus, earning higher income tomorrow. Impatient individuals will, therefore, choose to expend less search effort while unemployed. In this case, because the choice of how intensively to search for work involves trading off utility between the present and the future, both types of impatience predict a decrease in search effort.

Combining these two components yields the total effect of impatience on job search duration. There is a clear prediction that time-inconsistent impatience will lead to longer unemployment duration due to lower search effort and unaffected reservation wages. For time-consistent impatience, however, the two pieces of the decision go in opposite directions. Lower search effort reduces the likelihood that an unemployed person receives a job offer in any period, but a lower reservation wage increases the likelihood that the person will accept an offer once received. Thus, the sign of the effect of impatience on job search duration reveals whether the impatience is time-consistent or time-inconsistent.

Using various empirical measures of impatience (including interviewer ratings), the study finds robust evidence that impatient individuals have longer unemployment spells, providing substantial support for the predictions of the time-inconsistency framework. Figure 1 provides key results from other studies reaching broadly similar conclusions when examining the role of impatience in job search among the unemployed. These findings imply that for a minority of workers, incentives to exit unemployment earlier or to search more intensely for re-employment may improve individuals’ happiness, rather than encouraging them to accept jobs that they do not want.

On-the-job search

Searching for a new job while employed is another important determinant of the overall trajectory of an individual's career. One study shows that impatient individuals are more likely to switch to another employer rather than to invest in a relationship that leads to an internal promotion [11]. Although this behavior could occur for a variety of reasons, this fact can be interpreted as reflecting time-inconsistent impatience under two conditions. First, the rewards from switching employers must be experienced earlier, meaning that someone looking for an immediate increase in income would do better to switch jobs than to try to earn a promotion internally. Second, in the long term, maintaining a consistent relationship with a particular employer needs to lead to higher peak earnings. The study finds empirical support for each of these conditions and concludes that switching employers, even to take a raise, can be viewed as the less patient investment choice.

Another study corroborates the finding that impatient individuals are more likely to switch jobs overall [1]. In addition, it finds that, conditional on switching jobs, impatient individuals are much less likely to experience a substantial increase (at least 10%) in earnings as a result. This increased prevalence of job changes without a pay increase further supports the idea that impatient individuals fail to invest in long-term employment relationships that lead to substantial future earnings.

Implications for lifetime earnings

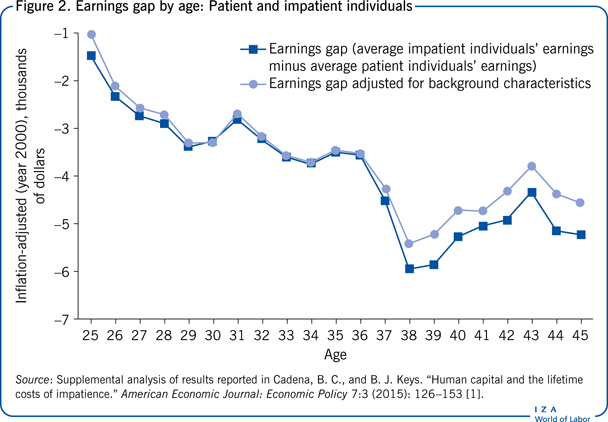

The combination of all of these factors is expected to lead to a substantial disparity in lifetime earnings between patient and impatient workers. Figure 2 presents a straightforward comparison of average annual earnings for these two types of workers using NLSY79 data and the interviewer ratings method of classifying individuals. The line with the squares shows how much less, on average, impatient individuals earn at every age than patient individuals do. Like many missed investment opportunities, the costs are small in the beginning, but the losses eventually compound. Early in their careers, impatient workers earn slightly less than their patient counterparts. By middle age, however, impatient workers are earning more than $5,000 less per year.

The line with the circles presents regression-adjusted annual earnings gaps, controlling for a host of background characteristics. This adjustment addresses the concern that measured impatience may reflect other characteristics that are known to influence people's investment choices and labor market experiences. These controls include parents’ education and income, gender, race/ethnicity, region of the country, urban or rural locale, and measures of parental investment in the respondent's education. The fact that the two lines are so similar supports the idea that impatience is not simply a proxy for other socio-demographic characteristics and that patience varies substantially within each of these measures. As reported in the original study from which this figure is adapted, the cumulative differences in earnings over these ages add up to more than $70,000 less for impatient individuals, a difference of roughly 13% [1]. Additional research has found similar percentage impacts on lifetime income in a different context (Figure 1).

Limitations and gaps

There is substantial evidence that dynamically inconsistent impatience affects a variety of important investments relevant for the labor market. There are, however, some important limitations in the literature. First, it is difficult to measure dynamic inconsistency directly, so nearly all of the empirical evidence relies on indirect ways of uncovering the importance of impatience. As a result, many of the results discussed above remain open to alternative interpretation. For example, individuals rated as impatient in an interview may lack other non-cognitive skills, and these deficiencies, rather than impatience per se, may lead to a lower likelihood of making internally consistent investment choices.

Relatedly, there are several strands of the economics and psychology literature investigating the importance of personality in general and the ability to delay gratification in particular. The empirical facts are common across these literatures: individuals who are able to exercise self-control and give up current pleasure for a long-term payoff are more successful. The theoretical frameworks across these disciplines, however, remain somewhat disconnected [12]. Additional work will be needed to more closely tie together the constructs of dynamically inconsistent impatience, non-cognitive skills, and conscientiousness.

Finally, one of the challenges in this line of research is that investments, especially in human capital, compound over time. As a result, impatient individuals have lower levels of cognitive ability as they approach future decisions. Especially with complex decisions, such as whether to forgo immediate earnings and take on student loans in order to earn a college degree, lower cognitive ability may lead to behavior that looks like time-inconsistent choices. Again, this pattern is fully consistent with impatience being the ultimate cause of the difference in choices. Nevertheless, teasing apart the importance of continuing impatient preferences from that of lower cognitive ability as a result of earlier differences in investment remains a potentially fruitful area for research.

Summary and policy advice

As summarized in Figure 1, there is considerable evidence that a minority of individuals make time-inconsistent choices as they invest in education and in their careers. Studies suggest that impatient individuals fail to stick with their original plan, whether that plan is to finish a degree, to search hard for a new job, or to invest the needed time and effort to gain a promotion. As a result, impatient individuals earn less than their patient counterparts over their lifetimes.

These results suggest a greater potential role for policies designed to encourage people to stay in school or to find a job when unemployed. In the absence of time-inconsistent preferences, people would make the choices that make them happiest, and government policy with the goal of changing these choices would rightly be viewed as paternalistic. Perhaps the least controversial policy prescription is to fund educational investments to develop younger students’ non-cognitive skills, including the ability to delay gratification. One promising model uses case studies and in-class games to teach elementary school students to make more forward-looking choices. A randomized evaluation of this intervention found that treated students showed more patience in incentivized laboratory tasks, and, importantly, they were also less likely to exhibit behavioral problems at school [13]. By addressing the root cause of impatience, investing in these types of programs could yield very large returns.

For older cohorts, however, evidence shows that it is difficult to change people's ability to delay gratification. For these cohorts, alternative policy interventions that support additional investment directly are likely to be the most effective. For example, immediate monetary incentives for continued study or lowering the financial costs to complete a degree for students close to the finish line may be especially helpful. Programs that pay unemployed workers to engage in consistent job search effort may also reduce time unemployed and improve workers’ satisfaction with their job search results. In fact, stricter constraints, such as raising the minimum age of compulsory schooling, may make the affected students happier if the share with self-control problems is larger than the share who would otherwise rationally choose to leave school. Of course, identifying impatient individuals can be difficult, and any financial incentive will likely also benefit individuals who would have completed these investments anyway. Nevertheless, the weight of the evidence suggests that these types of policies would help a substantial number of people achieve the investment goals that they desire but have trouble committing to.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Greg Madonia and Shusheng Zhong provided excellent research assistance. Version 2 adds new evidence that patience can be learned and incorporates recent studies of impatience in the labor market, resulting in updates to Figure 1 (previously Figure 2), new “Key References” [3], [8], [13], and updated “Additional references.”

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Brian C. Cadena and Benjamin J. Keys