Elevator pitch

The main goal of secondary school education in developed countries is to prepare students for higher education and the labor market. That demands high investments in study duration and specialized fields to meet rising skill requirements. However, these demands for more education are in opposition to calls for early entry to the labor market, to lengthen working lives to meet the rising costs associated with an aging population and to enable the intergenerational transfer of skills. One way to lengthen working lives is to shorten the duration of secondary school, an option recently implemented in Canada and Germany. The empirical evidence shows mixed effects.

Key findings

Pros

Shortening the duration of secondary school can make tax and social security systems more sustainable by lengthening people’s time in the workforce.

Shortening secondary school does not affect the probability of a student enrolling in college.

The effects of reforming secondary school duration on achievement in higher education are small and do not apply to all fields of study.

There is no evidence that reforming secondary school duration leads to an increase in the probability of dropping out of college or to lower enrollment in a university program.

Cons

Shortening secondary school reduces mathematics achievement in secondary school, indicating some limits on the ability of young people to accelerate the accumulation of knowledge.

Shortening secondary school increases the likelihood that female students will delay college enrollment and decreases the likelihood that they will study science, technology, engineering, or mathematics.

Small negative effects on students’ personality development due to compression of the secondary school curricula may have a minor effect on later labor market outcomes.

Author's main message

Shortening secondary school can boost the sustainability of tax and social security systems by enabling people to work longer. It can also ease the rising shortages of skilled workers through intergenerational transfers of know-how. On the downside are signs of adverse effects on women’s achievement in secondary school and university, delay of university enrollment, and choice of field of study, together with small negative effects on personality traits associated with success in university and the labor market. If the reform can be organized so that pros outweigh cons, graduation from school after 12 years should be adopted.

Motivation

The optimal level of schooling has long been a topic of debate. The duration of schooling is important because time spent in school contributes to the development of skills and helps young people discover their preferences and interests and develop their talents. Much of the empirical research on this question has therefore focused on the relationship between years of schooling and wages. Studies over the last four decades have clearly established a positive correlation, and some have even established a causal relationship. As a result, many countries have compulsory schooling laws that extend the number of years children are required to go to school.

Although longer compulsory schooling has positive effects for the individual and for society in both monetary and non-monetary rewards, it also incurs higher societal costs. Since longer schooling generally means later entry into the labor market, policymakers face a trade-off between the length of schooling and the length of labor force participation. The pressure to resolve this trade-off is intensified by the aging of the population in many countries, which is straining tax and social security systems and leading to rising shortages of skilled workers, as well as by the delayed intergenerational transfer of know-how. The key question is whether it is possible to resolve this trade-off by shortening the duration of secondary schooling while maintaining its quality.

Discussion of pros and cons

Options for reducing the trade-off between length of schooling and length of labor force participation

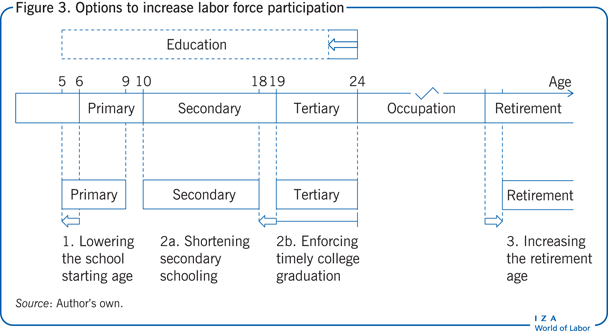

To reduce the trade-off between the length of schooling and the length of labor force participation, policymakers have several options: lowering the school starting age, compressing the time in school, and raising the retirement age. The options are not mutually exclusive but may be blended in various combinations.

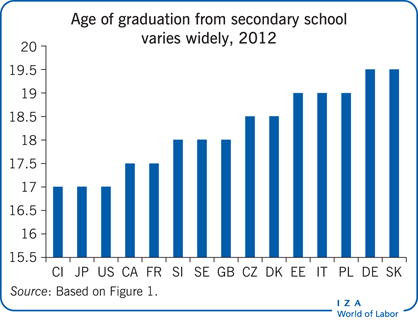

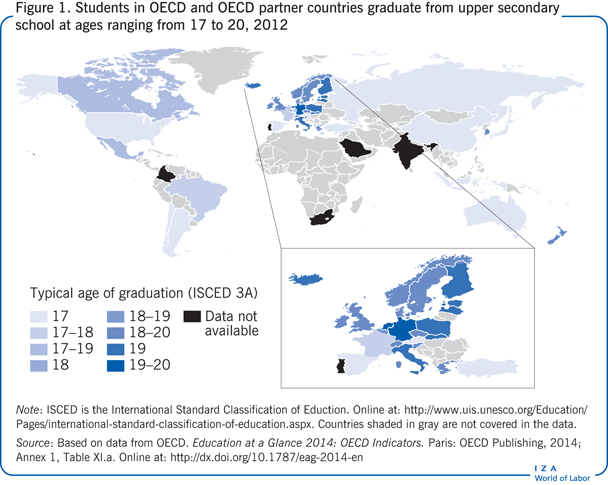

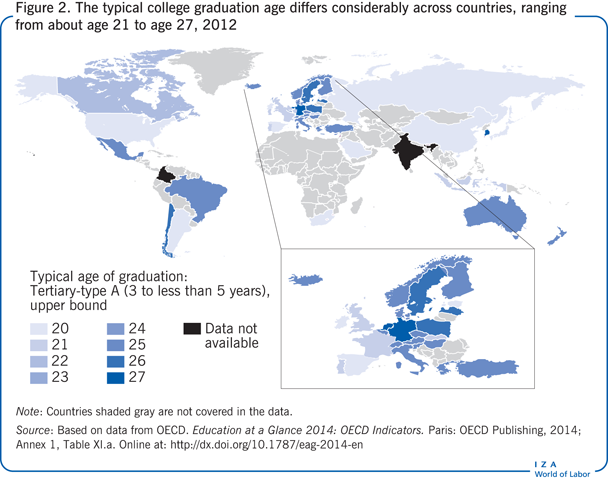

Students in OECD and OECD partner countries graduate from upper secondary school between the ages of 17 and 20. Late graduation is particularly common in continental and Eastern Europe (Italy, Finland, Germany, and Poland, for example; Figure 1). College graduation age thus differs considerably across countries, ranging from about 21 to 27 years of age (Figure 2). The later students graduate from secondary school, the later they enroll in and graduate from college, which further delays labor market entry.

These data imply that there is some scope for earlier labor market entry by lowering the graduation age, whether by dropping the school starting age or compressing time in school. Several countries have recently lowered the school starting age, including Japan, Poland, and Switzerland. But flexibility here is constrained by the biological limitations of child development: primary school already starts at around ages five to six in many countries. Compressing schooling duration can be organized in different ways. One possibility is to accelerate college graduation by encouraging graduation within the traditional timespan, perhaps through financial incentives and penalties. Another possibility is to shorten the length of secondary school by preparing students for college and work in fewer years. The third option is raising the retirement age, which seems like a rational response to higher life expectancy and improved health status. In practice, however, raising the retirement age has proved politically unpopular in many countries. (Figure 3 illustrates these three options.)

This paper focuses on the option of compressing time in secondary school. Shortening the duration of secondary schooling while maintaining quality and qualifications for college enrollment requires compressing curricula and therefore increasing learning intensity (the amount of content learning per unit of time). Understanding the relationship between learning intensity in school and human capital accumulation is important to avoid over-burdening or under-stimulating students. Empirical research has focused mainly on variations in instructional time, which can have a causal effect on school achievement [1]. Lengthening the school day raises achievement [2], while reducing instructional time lowers it [3].

Experience with shorter-duration secondary school

Recent reforms of secondary school duration, eliminating a whole year of education, were implemented in Ontario, Canada, during 1999–2003 and in several German states beginning in 2001 and slated for completion in 2016. The reforms in both countries shortened university preparatory schooling from 13 years to 12 years, but the details differ in several respects. (Germany also implemented shorter school years nationwide in the 1960s for all school tracks, when it changed the start of the school year from winter to summer [4].)

The Ontario reform was motivated by a desire to bring practice in the province in line with that in most of the rest of Canada and the US [5]. In 1999, high school (starting in grade 9) was shortened from five (grades 9–13) to four years (grades 9–12). While the curriculum was compressed, students still had to complete the same number of credits (30). The main change in the curriculum affected university-bound students. University admission requirements include six so-called Ontario Academic Credits (OACs). These senior-level courses are related to the university program a student plans to follow. Completion of an OAC credit required attendance in two basic courses during grades 9 and 10, an advanced pre-OAC course, and the OAC course [6]. As part of the reform, all the intermediate-level pre-OAC courses had to be taken in grade 11, and the OAC course in grade 12. In addition, the curriculum was adjusted in some subjects. For example, under the new system students were expected to take four mathematics courses instead of five [5].

States in Western German had a decades-long tradition of 13 years of schooling for graduation from gymnasium (lower and upper secondary school, grades 5–13). The length of schooling came under increasing scrutiny in the late 1990s, especially following reunification with East Germany, which required just 12 years of schooling to graduate from gymnasium. Initially after reunification, most East German schools adopted the West German system. Then, between 2001 and 2008, most federal states eliminated the last year of secondary school (grade 13). The exceptions were Saxony and Thuringia, which had maintained 12 years of schooling after reunification, and Rhineland-Palatinate, which left its system of 12.5 years unchanged. The reforms will not be fully in place until 2016.

While implementation of the reforms was similar across German states, there have been some differences. For example, in many states the first affected cohort were students entering grade 5, but in some states the change was introduced in higher grades. Graduation requirements were maintained in all states, and the curriculum was compressed into the shorter school duration. The reform was completed first in Saxony-Anhalt in 2007. As it was introduced in 2003 and affected students enrolled in grade 9, it reduced the graduation requirement in upper secondary school from five years to four years, similar to the reform in Ontario. The main difference from Canada, however, is that curriculum and teaching hours were not changed. Thus, it is easier to analyze the impact of compressing educational duration, since nothing else was changed.

Theoretical implications for the education system and the labor market

Both the Ontario and the German reforms have implications for the education system and the labor market. The main aim of the reforms was to achieve the same level of education in less time, meaning that secondary school graduates would be able to start their university education and, subsequently, their career one year earlier. As a consequence, students had to master the same (or almost the same) curriculum within a shorter time. To achieve that, learning intensity would have to increase considerably.

Several theoretical approaches have been pursued to explore students’ post-secondary school education decisions—whether to start vocational education or study at university and which field to study. At least three major determinants of these decisions have been identified: expected returns, expected costs, and expected probability of successful completion. Theoretically, this reform could have both positive and negative effects on student progression to higher education. On the positive side, the higher education intensity in the compressed curriculum could improve the efficiency of learning and the ability to cope with academic requirements. If the efficiency of learning and the ability to cope with academic requirements improve, students’ education decisions after secondary school should not be affected.

On the negative side, the reform could be detrimental to learning outcomes if, for example, it overtaxes students, curtails options for more in-depth learning, and leaves them less prepared for higher education and more likely to delay entry or fail to complete a full course of university study [1]. If students are overwhelmed by the more intensive instructional load and if teachers are unable to explore topics in enough depth, students could be (or feel) less prepared for university and might choose a less demanding track or subject after secondary school [7]. Students might also make less wise post-secondary school education decisions because of their greater youth and relative lack of experience after 12 rather than 13 years of schooling. Time in school not only imparts knowledge and skills, but also helps students discover their talents and preferences. With one year less to identify their strengths and develop occupational preferences, and with less experience of life, students’ insecurity about what to do after secondary school could increase. As a result, students might delay entry into post-secondary school education or begin with a less demanding course of education (as a precaution) [8].

The increased workload might also affect students’ personality development, through such diverse mechanisms as persistent shifts in inputs to personality formation, more general environmental changes, and simple changes in constraints or other factors that are relevant to student decision-making [9]. There may also be gender differences in the effects of reforms as a result of gender-specific learning modes [1]. Finally, for any secondary school reform, there will be two distinct streams of students: those applying for university [10] and those transitioning directly into the labor market [11]. Some studies indicate that there is a relationship between the shortened duration of secondary school and that decision.

Results of empirical studies

Achievement in high school and secondary school graduation age

Only the German reforms have been studied for the impact of compressing secondary school education on school achievement. The results vary by academic subject [1]. No effects are found for achievement in German literature. Because German is the native tongue, knowing it well promotes a feeling for language and is useful for developing competence in communication. However, the reform has significant negative effects on mathematics, which requires logical thinking and a capacity for abstraction. While both male and female students are negatively affected, the average impact is larger for men (about 10.9%) than for women (7.9%). These findings imply that there are limitations on the ability of young people to accelerate the accumulation of knowledge. The differences between courses can be explained by differences in exposure and content: whereas mathematics requires learning new fields (for example statistics) and new methods and understanding underlying concepts, German courses focus on refining and applying familiar concepts. In addition, students use their native language in their everyday life, while their exposure to mathematics content is more often confined to the classroom [1].

The main aspect of the reform—shortening secondary school by one year—may not be achieved if grade repetition increases or students drop out because of the increased learning pressure. Canadian evidence on repetition and drop-out rates is not reported, but the empirical estimates for Germany indicate that the reform has reduced the mean graduation age by about 10 months, or two months short of the potential of one full year [12]. However, although the increased learning intensity affected grade repetition (up three percentage points), there were no adverse effects on completed education.

Choice of higher education programs and institutions

The empirical findings show that shortening secondary school has some adverse effects on the choice of higher education options. In Germany, female students were significantly more likely to delay university enrollment after the reform. Following the reform, they had a greater probability of pursuing vocational education in the German apprenticeship system before attending university, delaying enrollment an average of three years. Despite this delay, however, the reform did not lower university attendance overall [7]. For male students, there was no change in enrollment behavior.

The reform also affected female students’ choice of field of study, but not men’s. Women were less likely to study science, engineering, technology, or mathematics (STEM subjects), especially natural sciences and mathematics, but more likely to choose medical sciences [7]. The findings can be attributed to two main channels of impact, an orientation effect and a performance effect. The effects on enrollment decisions might be explained by younger students in the German education system being less well oriented in terms of occupational tastes and talents. Second, the reform had a negative effect on student skills. This performance effect may also explain the impact on decisions about university enrollment and university subjects. Thus, instructional time and learning intensity at school, especially as they help students discover their talents and occupational interests, are also relevant to subsequent education choices.

Success in higher education

Empirical studies suggest that performance in high school is the most important determinant of success and persistence in higher education. From a theoretical perspective, shortening the duration of secondary school could have either positive or negative effects. Empirical findings for Ontario and Germany are mixed.

Most students who enrolled in an Introductory Management class in the University of Toronto experienced the policy change, and had four years of secondary school rather than five. The compression of secondary education had a negative effect on university achievement: the grades of secondary school graduates who had received five years of secondary school education averaged about one-half to one full letter grade higher than those of graduates under the compressed four-year schedule [6]. The advantage is smaller when only high-ability students are considered. For students enrolled in the Life Sciences program (which can be expected to require high mathematics competence), the benefit of an extra year of high school mathematics was small: students coming out of grade 13 had a 2.3 point advantage (on a 100-point scale) over students from grade 12, representing a 0.17 standard deviation in mathematics performance [5]. One likely explanation for the small gain from an extra year of schooling is that high school teachers direct more attention to lower-performing students, leaving fewer resources for high-performing students. It is also possible that high-performing students can make up for the missing year of mathematics “effortlessly” [5].

For the German reform, no information on students’ university grades is available. Nevertheless, empirical findings indicate that shortening secondary school had an impact on students’ subjective perceptions concerning learning difficulties and feeling burdened. Female students graduating after 12 years of schooling were significantly more likely to report experiencing learning difficulties and skill deficits in university education, but felt less burdened by personal problems and concerns. Male university students affected by the reform felt more burdened by performance requirements and time pressure. However, there was no evidence of greater difficulty enrolling in a university program or of an increase in the probability of dropping out of university education [8].

Effects on personality traits

The compression of secondary education into fewer years may also affect the personality of students. The related literature on scholastic achievement sees academic performance as a combined signal of underlying personality traits (such as self-discipline, perceived control, and agreeableness) and cognitive abilities (such as fluid intelligence and numeracy). In this view, scholastic achievements are mediating factors rather than genuine outcomes within the context of human capital theory.

For the German reforms, the effects are ambiguous and differ across the traits examined [9], [13]. Effects are expressed in standard deviations since scale scores for personality traits are not inherently meaningful. All the reported effects are small compared with a rule-of-thumb threshold of 0.2 standard deviations for this style of expression. For male students, the reform has statistically significant average effects on openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, locus of control, and self-control [9]. As a result of the reform, openness increases (0.086 standard deviations), and conscientiousness improves slightly (0.038). There is a small negative effect of about the same size on extraversion. The negative effect on locus of control is slightly larger (−0.098), as is the effect on self-control (−0.099). The largest average effect of the reform is a decrease in neuroticism (–0.185). For female students, the reform has statistically significant average effects on conscientiousness, extraversion, and locus of control [9]. The average effect on conscientiousness is negative (−0.097), but comparatively moderate, and the effect on extraversion is positive, but small (0.095). Both effects are in the opposite direction from those for male students. The effect on locus of control is negative (−0.066 standard deviations), as it is for male students.

Since not all personality traits are equally rewarded in the labor market, what do these effects mean economically? Translated into hourly wages for someone of working age, the effect size for locus of control (a highly rewarded personality trait in the labor market) would be a 0.7% decline in average hourly earnings for men and a 0.5% decline for women [9]. The stronger average effects for neuroticism would barely transmit into hourly wages, however, since the wage gradient for this trait is almost zero in the labor market.

Gender effects

As discussed, there are differences in how shortening the duration of secondary school affects male and female students. Changes in learning intensity at school had a larger negative effect on mathematics achievement for male students (performance effect) [6]. Female students felt less prepared or less oriented toward university education (orientation effect), resulting in lower university enrollment of female students in the first year after high school graduation compared with female students before the reform [6], [7]. In Germany, female students affected by the reform had significantly more problems with assessing the skills required in post-secondary school education and had greater uncertainty about their own interests; male students affected by the reform did not [7]. As a consequence, female secondary school graduates might have been more likely to choose vocational education over university education, as a precautionary measure. With respect to performance in university, evidence for Ontario shows that average grades and the proportion of students graduating on time increased for male students more than for female students [10]. In line with that finding, female graduates of shortened-duration secondary schools evaluated their success probability at university lower than male students [8].

Limitations and gaps

From a cost–benefit perspective, the reforms are likely to be efficient if they imply longer labor force participation and if the associated tax and social security contributions are not considerably lower than for students who are in secondary school one year longer. But more evidence is needed to establish these long-term outcomes. One limitation of the evidence to date is that it refers mostly to the double cohorts of graduates from school in one year. Although all the studies reviewed put considerable effort into making the estimates generalizable by ensuring external validity, studies on the long-term effects on higher education choices and success are not yet available. Similarly, information on the direct or indirect labor market impacts of the reform on occupational choices, wages, and unemployment probabilities have not yet been reported. In addition, the reasons for the differences by gender in the effects of the reform have not been identified or comprehensively analyzed; neither have the consequences of these differences.

Summary and policy advice

Shortening the duration of secondary school can enable earlier and potentially longer labor force participation and therefore contribute to the sustainability of tax and social security systems. Such a reform could also improve the transfer of know-how across generations that is required to ease rising shortages of skilled workers as baby-boom generation workers leave the labor market. For these reasons, it can have positive effects for society in general. However, shortening the duration of secondary school has some adverse effects on academic achievement in secondary school, on the choice of a college education, and on academic achievement in university. In addition, since secondary school is a formative period in the development of a student’s personality, some related negative effects have been identified as well. Moreover, in all these dimensions, differences between genders have been shown.

The findings have several implications for policymakers. In reducing the duration of secondary school, curricula adjustments should consider not only the standards to be achieved but also any excessive burdening of students. Students’ orientation problems, in terms of performance difficulties and less well defined occupational tastes and talents related to the choice of a university education program should be taken into account when designing university preparatory schooling curricula. Particular aspects of students’ personality traits and development should be considered so as to avoid unintended side effects. Finally, given the clear differences in effects by gender for all outcomes, gender-specific behavior and requirements should receive special attention.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author (jointly with Bettina Büttner, Tobias Meyer, and Hendrik Thiel) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [7], [8], [9]. Financial support of the German Research Foundation (DFG, grant TH1499/2-1 and TH1499/2-2) is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Stephan L. Thomsen