Elevator pitch

Employers want motivated and productive employees. Are there ways to increase employee motivation without relying solely on monetary incentives, such as pay-for-performance schemes? One tool that has shown promise in recent decades for improving worker performance is setting goals, whether they are assigned by management or self-chosen. Goals are powerful motivators for workers, with the potential for boosting productivity in an organization. However, if not chosen carefully or if used in unsuitable situations, goals can have undesired and harmful consequences. Goals are a powerful tool that needs to be applied with caution.

Key findings

Pros

Using goal-setting techniques can increase workers’ motivation and performance.

Goals are especially effective if the work task has a simple structure.

Individual work goals can increase performance, whether assigned by management or chosen by the worker.

Even when monetary incentives are already high, complementing those incentives with goal setting can improve performance.

Similar to the effect of monetary incentives, goals help to focus attention on the most important parts of the work task.

Cons

Goals that focus solely on output quantity can lead to lower quality outputs.

If assigned goals are too ambitious, excessive risk taking may result.

Work goals that are based on the output of individual workers can reduce cooperation among workers.

Goals can encourage unethical behavior and lead to overcharging and misreporting of performance measures.

Many of the caveats that apply to monetary incentives also apply to goal setting.

Author's main message

Empirical field and laboratory studies demonstrate that well-chosen work goals, whether assigned or self-chosen, can increase employee productivity, with and without monetary incentives. Goals are most productive in simple work environments, where productivity is defined along a single dimension of effort, such as output quantity, and where chances for adverse behavior are low. In more complex environments, multidimensional goal setting is harder to get right and can lead to undesirable behavior and ultimately to lower quality. Broader organizational objectives should be communicated to workers to avoid too narrow a focus on some goals.

Motivation

Goals are everywhere in human life and organizations. For example, in our private life we set goals for saving money and losing weight. In politics, politicians debate fiscal goals, goals for reducing carbon dioxide emissions, and goals for job and wage growth, among many others. Similarly, in our working life we try to achieve tenure or promotions. At work, we may face sales goals, revenue goals, project milestones, and production goals. Some of these goals are specific, some are vague, some are binding, and some are backed up by monetary incentives. And some goals are self-chosen while others are imposed externally.

New forms of management structure in recent decades, such as management by objectives, described by Peter Drucker in the 1950s, have been heavily influenced by goal-setting approaches. In particular, large technology firms such as Google, Intel, and Twitter have started to use goal-setting approaches to provide real-time feedback to their workers.

In psychology, the research on goal setting has a long tradition. Studies have consistently demonstrated that an individual’s behavior is affected by goals and that, if well chosen, goals can boost individual productivity. More recently, economists have jumped on the goals bandwagon, adding formal theories to model the functioning of goals and contributing to the empirical evidence. While many studies have found positive effects of goal setting, some cautionary notes on possible adverse side effects have emerged from this research.

Discussion of pros and cons

Properties of well-designed goals

Management theorists and practitioners broadly agree that goals should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timed (SMART). Specific means a well-defined goal in an explicitly established unit of measurement (such as dollars for revenue, pieces for output, and pounds for weight loss) as opposed to a simple “do your best” rule. Measurable refers to the ability to observe progress so that an individual (and observer) knows how close goal attainment is. A goal should be attainable, which means that an individual has a realistic chance of achieving the goal. To be relevant, a goal needs to be meaningful and worth achieving for the individual or the organization. And finally timed implies that there should be some time limit for reaching the goal (for example, lose five pounds by the end of the month or increase revenue by $100,000 in the first quarter of the year).

Positive effects of goals

Among economists, the prevalent view on goal setting is that workers are driven by two types of motivation. First, they are extrinsically motivated by the wages they receive, and second, they are intrinsically motivated to reach their personal goals. Consequently, goals provide a reference point against which workers can measure their satisfaction (utility) by dividing outcomes into gains, when the goal is attained, and losses, when output falls below the goal [2], [3], [4], [5]. In line with prospect theory, losses (outputs below the goal) hurt more than gains (outputs above the goal) feel good. Consequently, workers will be risk-seeking and willing to exert higher effort to prevent the dissatisfaction (disutility) experienced as a result of failing to attain the goal.

Increased productivity

Organizations often combine work goals with bonuses that are paid once the goal is reached. In those settings, a worker could be motivated not only by the goal itself, but also by the prospect of a monetary reward. However, even goals that are not linked to monetary rewards can be very effective in increasing productivity. In a recent laboratory experiment, subjects in the role of workers had to engage in a laborious mathematics task requiring close effort for 1.5 hours [5]. Each correct solution generated revenue that was split equally between the worker and a manager. The higher the number of problems the worker solved, the higher the earnings for the worker and the manager. Because the task was long and required close concentration, workers had the option of taking breaks to engage in some on-the-job leisure activity. Workers could explore the internet whenever they wanted or needed a break. Some managers could assign goals in the form of an explicit number of correctly solved problems. Achieving or not achieving the goals did not affect the amount of earnings workers received, and managers were unable to fire workers who did not achieve their goals.

In this setting, goals had no direct influence on the final earnings of workers. Still, when given the option to set goals, managers did so, setting goals that were challenging but attainable for an average worker. Workers responded to the goals by increasing their output and decreasing their on-the-job leisure activities. Thus, goals seem to be a means of transmitting managers’ expectations to workers, and workers respond. Although the assigned work goals do not affect wages, they indirectly boost the earnings of workers and their managers by increasing productivity. Goals were effective in boosting productivity even when monetary incentives were already high—even when workers were already being paid a high sum for each correct solution.

The effectiveness of assigned work goals for improving productivity has also been confirmed in field experiments. In field experiments, subjects are observed in real work environments while being unaware of their participation in a scientific experiment. Thus, field experiments allow for the implementation of subtle manipulations without subjects feeling the experimenters’ scrutiny. One field experiment was implemented in a research institute library that needed to be restructured [1]. During the rearrangement, roughly 35,000 books had to be found and moved from one shelf to another. Temporary workers hired for this one-time-only job were the unknowing participants in an experiment on goal setting.

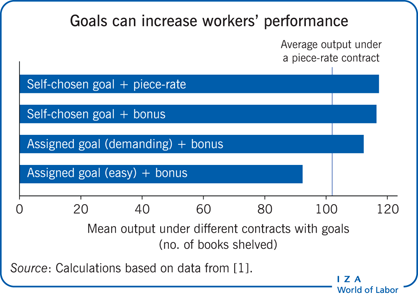

For some workers, librarians assigned goals for the number of books to be located and reshelved during a shift. In line with the findings of the laboratory study, having goals did increase workers’ productivity—in this case by 15% compared with a baseline case without goals (see the Illustration on p. 1). Other workers were free to choose their own goals before starting work. Again, having a goal increased workers’ output by 15%. Thus, the same positive effect was observed whether the goal was assigned by a manager or chosen by the worker [1].

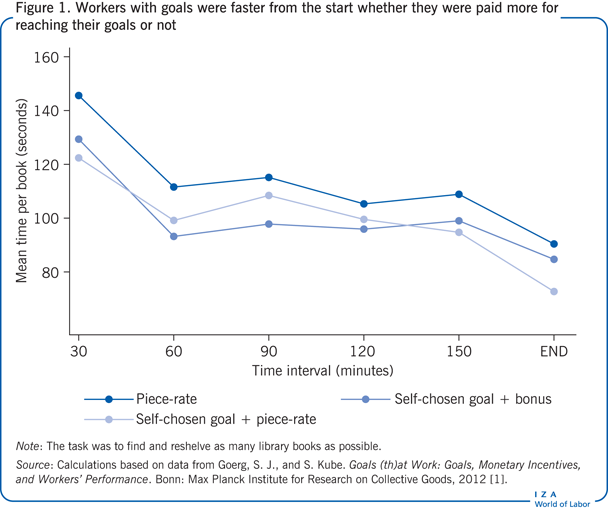

The study also investigated whether the impact varied when goals had monetary consequences and when they did not [1]. In one experiment, workers with self-chosen goals received the same piece-rate pay as in the baseline experiment, and goals were chosen independently from this payment scheme. In another experiment, self-chosen goals had monetary consequences: workers received a bonus only if they reached their goal. Figure 1 gives the average time needed to find one book. As workers improved over the course of the experiment, the average time needed to complete the task declined. However, in both experiments with goals, whether workers were paid more for reaching their goals or not, workers were faster right from the start and needed significantly less time to find a book. Whether goals had monetary consequences did not affect the time needed to complete the task.

Self-chosen or assigned goals and accuracy of goal setting

The field experiment also provides some interesting insights into the differences between self-chosen and assigned goals and on the effects of the difficulty of the goal [5]. While self-chosen and assigned goals led to the same increase in average productivity, they led to different distributions of outputs.

The variance in output was much smaller for assigned goals than for self-chosen goals. Self-chosen goals were much more diverse and therefore resulted in a more diverse set of outputs. When all workers are assigned the same goal, each worker has the same reference point for assessing success. Thus, most of the output will be close to this reference point. The effectiveness of the goals thus depends on whether this reference point is motivating for the average worker—whether the goal falls in the sweet spot between too demanding and too easy. In the field experiment, the assigned goals were chosen relative to the average productivity of workers in the baseline without goals. Using this information, it was possible to identify and assign both demanding and easy goals. Compared with the baseline without goals, productivity increased significantly with the demanding goal but dropped below the level of the baseline with the easy goal (see the Illustration) [1].

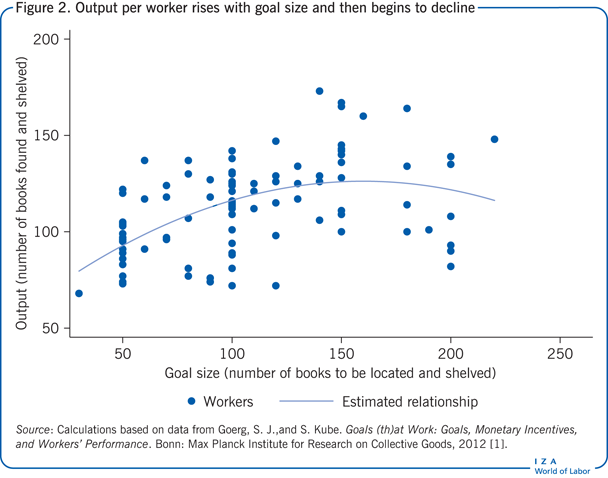

Figure 2 presents the goals and the corresponding output as observed in the library study [1]. The curve represents the estimated relationship between the difficulty of the goal (goal size) and output. Starting from easy goals (fewer books), output increases with goal difficulty up to a certain point: the harder the goal, the more productive the workers. But the relationship is not linear. The inverse U-shape of the curve shows that while output increases initially with goal difficulty, beyond a certain difficulty level, the positive impact on output declines.

In the work environment of the field experiment, the average output for a goal of 200 books was not much different from the average output for a goal of 100 books; the highest average output was achieved for a goal of 150 books. This result underlines the finding that a goal should be in a reasonable range of a worker’s ability level—neither too easy nor too demanding. If the goal is too easy to achieve, it cannot motivate a worker because once the goal is achieved it no longer provides an additional reason to continue to work hard. Thus, an easy goal is unlikely to lead to substantially higher outputs compared with a situation without a goal. However, if the goal is too difficult, the worker will no longer feel bound to the goal as soon as it becomes obvious that the goal is not attainable. This effect is in line with the previously reported laboratory evidence [5].

The specifics that determine whether a goal is too easy to attain or too hard depend on the characteristics of the work environment and on the ability of individual workers. Management could try to adjust the goal to the ability level of each worker. But different goals and different bonus payments could result in dissension and unfavorable comparisons in the workplace, which could jeopardize the positive effects of individualized goal setting. Moreover, individual adjustments could have high implementation costs, and management would need to have an exact measure of the ability of each worker.

If workers decide on their own goals, they will choose goals based on their perceived ability. If the ability differs considerably across workers, the result will be greater variance in chosen goals and in output. With self-chosen goals, high-ability workers will choose demanding goals and excel at the task, while low-ability workers might choose goals that are below average. Assigning the same goal to all workers engaged in the same task will result in lower variance in output and less uncertainty about total expected output. Yet, for the goal to be attainable by a large share of a diverse work group, it has to be set at a relatively low level, making it easy to attain for high-ability workers and thus discouraging high performers from excelling in productivity. At the same time, it will help to motivate low-ability workers and potentially increase their output.

Whether self-chosen goals or assigned goals are the preferred mechanism depends on the manager’s objective. Self-chosen goals should be used if the manger wants to encourage high-ability workers to excel in their performance and if it is acceptable that low-ability workers produce significantly less than the average. Assigned goals should be used if the objective is to reduce the variance in output, potentially increasing low-ability workers’ output at the cost of discouraging high performance.

Adverse effects of goals

While in general the potential of goal setting is not disputed, cautionary notes on possible negative side effects have emerged. In particular, “stretch” goals—goals that are extremely difficult to attain—which have been advocated by some management consultants, have come under heavy criticism. Unrealistic stretch goals on roll-out timing and production costs have been linked to the deadly design mistakes of the Ford Pinto in the 1970s, unreasonable sales goals have been linked to the overcharging of customers at Sears auto repair centers in the 1990s, and goals focusing solely on revenues to the neglect of profits have been linked to excesses at Enron in the late 1990s.

Goals can be used to motivate workers and induce higher productivity, just as monetary incentives can. However goals can have additional, unintended effects leading to adverse behavior: They can lead to the wrong focus in settings with multitasking [6], to reduced cooperation among workers [7], to increased risk taking [8], and to unethical behavior [9]. The same effects have also been identified for monetary incentives [10], [11].

Goals can lead to the wrong focus and lower work quality

Performance-related payment schemes are used to focus workers’ attention on the important parts of a job; the same holds true for assigned goals. But if this focus is too narrow, workers will miss the broader dimensions of a task. For example, workers with output quantity goals might focus their attention on the quantity dimension and disregard the quality of the output as less important. Similarly, if management sets only revenue goals for a company, profits might receive inadequate attention. In some cases, an intense focus on defined goals might result in a failure to notice the need to revise some tasks to improve efficiency or quality, for example, or to correct faulty procedures, revise job descriptions, or innovate on the task [12]. Thus, goals can result in rigid, bureaucratic behavior instead of good performance and good organizational citizenship.

The obvious solution to prevent too narrow a focus would seem to be to define broader goals covering multiple dimensions instead of just one. The drawback is that having multiple goals can require trade-offs among goals. In situations with multiple goals, people generally devote more attention to the goals that are easiest to measure [6]. In an experiment, people whose goals were to select stocks for investments based on quality and quantity dimensions exhibited precisely this shift of attention from quality to quantity. Stock quality, which had to be determined from a stock’s rating, previous dividends, previous profits, and long- and short-term trends, was much harder to measure than the number of stocks selected. As the difficulty increased for both goals, participants focused more on the quantity and ignored the harder to measure quality. Expending less effort on the assessment of the quality of investments could eventually result in financial losses.

High goals can lead to increased risk taking

Losses can result from choosing a strategy that is too risky as well as from paying too little attention to some goals and too much to others.

Empirical evidence suggests that goals can directly influence an individual’s willingness to take risks [8]. In inherently risky environments, individuals will be more risk seeking if they are assigned high financial goals than if they are simply told to do their best. This finding is quite robust; it applies to making strategic decisions in bargaining environments, but also to choosing between safe options and risky gambles or lotteries. In bargaining situations, people given a high goal were less likely to adjust their offer, even when it meant not closing on a mutually beneficial deal. In the case of a risky investment, where the choice was between a safe option and a risky lottery, 37% of people who were told to do their best favored the safe option, whereas only 11% of people given demanding goals chose this option [8]—the rest chose the much riskier lottery.

Having individual rather than group goals can reduce cooperation

Good organizational citizenship involves more than working to expectations. It also involves interacting effectively with co-workers. When workers focus on attaining an individual goal, that can also influence the social environment in an organization. As discussed, having goals leads to higher performances while simultaneously reducing the amount of time spent on activities not directly related to the goal. Some forms of cooperative activities are desirable in an organization but are not captured by a simple goal. Thus, goals can reduce cooperation at the workplace if workers who are single-mindedly committed to achieving a difficult goal have a tendency to help co-workers less often [7]. This problem is intensified if the goals are accompanied by bonuses for goal attainment.

Goals can encourage such unethical behavior as cheating and misreporting

This paper has touched on some of the negative effects of having goals, such as overcharging customers to meet unreasonable sales goals and other unethical behavior. Setting goals can also lead to misreports about performance measures, for example, by falsifying the time worked on a project or the number of billable services performed. Laboratory evidence suggests that in work environments with self-reported performance measures, workers with unmet goals tend to overstate their performance while workers charged with doing their best do not exhibit such behavior [9]. In the study, participants were paid for performing a task requiring real effort. After finishing the task, participants were asked to evaluate their own results and to submit their evaluation to the researchers. Participants were ensured anonymity, so while the researchers could look at the self-evaluations they could not link them to specific workers. Comparing the incidence of overstatements for participants who were assigned a goal without monetary consequences with those for participants who were told to do as good a job as they could revealed significantly higher misrepresentation of performance among participants who were assigned a goal.

That the misrepresentation occurred in an environment guaranteeing anonymity rules out the likelihood that this behavior was driven by the desire to impress others. Most likely, participants were trying to maintain a positive self-image. Adding a bonus for each completed goal amplified the number of misreports. With monetary incentives, overstating one’s performance now affected not only one’s self-perception but also increased one’s earnings. Participants who were close to meeting their goal were the likeliest to behave dishonestly. These findings were replicated in a study that repeated the experiment with different levels of goal difficulty [13]. In this setting, participants produced the highest output for the highest goals. Low goals resulted in lower productivity than did an injunction to do your best. The downside of the increased productivity was the simultaneous increase in unethical behavior. Compared with the easy goal and with a do-your-best environment, in a high goal environment, participants were three times more likely to overstate their own performance.

Limitations and gaps

While there is ample laboratory and field evidence demonstrating that goal setting leads to better performance, most of the adverse effects of goals have been studied only in laboratory settings. Reports on adverse effects of goals in natural work environments are often based on case studies or anecdotal evidence providing narratives that are in line with the results of laboratory studies. Studies providing causal evidence from the field are rare. This is due mainly to the difficulties in systematically measuring and manipulating the study conditions in a real work environment to study, for example, unethical behavior. Nevertheless, more field studies on the potentially negative effects of goals would be welcome. Furthermore, while the literature has demonstrated that goal setting can result in adverse behavior, future research should address the question of how to overcome these side effects by organizing work environments so that only (or primarily) the positive effects of goal setting remain.

Summary and policy advice

The benefits of performance goals are widely documented. It has been repeatedly shown that specific and challenging goals lead to better performances than do easy goals or do-your-best rules. Goals boost performances by motivating increased effort, a stronger focus on the task, and a reduction in on-the-job leisure.

The downside is that goals come with a long list of potential side effects. Setting the wrong goals can lead to a too narrow focus, reduce cooperation in the workplace, increase risk taking, and encourage unethical behavior. Nearly all studies on the negative side effects of setting goals have observed improved performance on the main task, but at the cost of adverse behavior in other dimensions. One possible way to avoid adverse behavior is to include strong monitoring along with goal setting. However, workers could interpret increased monitoring as a sign of distrust and reciprocate by reducing their effort. So while monitoring might reduce the negative effects of goal setting, it might also reduce workers’ motivation and thereby the positive effects of goal setting.

In sum, it seems prudent to set goals in simple work environments, where output is determined by a single measurable input and where chances for adverse behavior are low. In more complex environments, goals should be SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timed), and broader organizational objectives should be communicated to workers. Clear communication between management and employees might help to calibrate goals so that they do not become too challenging and do not narrow the focus of attention too much. Thus, whether as an adjunct to monetary incentives or independently, goals can potentially provide motivation for higher productivity.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. He also thanks Sebastian Kube for comments on earlier drafts. This paper has drawn extensively on previous work by the author [1].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Sebastian J. Goerg