Elevator pitch

Arguments for increasing gender diversity on corporate boards of directors by gender quotas range from ensuring equal opportunity to improving firm performance. The introduction of gender quotas in a number of countries, mainly in Europe, has increased female representation on boards. Current research does not unambiguously justify gender quotas on grounds of economic efficiency. In many countries, the number of women in top executive positions is limited, and it is not clear from the evidence that quotas lead to a larger pool of female top executives, who, in turn, are the main pipeline for boards of directors. Thus, other supplementary policies may be necessary if politicians want to increase the number of women in senior management positions.

Key findings

Pros

Quotas increase the number of women on boards of directors (BoD).

The decision-making process improves with greater gender diversity on boards.

There are positive spillover effects from women on BoD to gender diversity among top executives.

Having female top executives may positively affect women's career development at lower levels in the organization.

Cons

Boards with diverse members or members who differ from the company’s senior executive management may experience communication problems internally and with management.

Quotas may imply overburdening the small number of qualified women or accept less experienced candidates.

Quotas seem to have little positive effect on increasing the pool of women with senior executive experience.

Despite a few positive outcomes, most short-term performance effects of female board members are insignificant or negative.

Author's main message

From an economic efficiency perspective, ensuring good female candidates for board positions requires widening the pipeline of women progressing to senior management and top executive positions. Policymakers may have to change their focus from requiring quotas for the top of an organization to the much broader task of getting a more balanced gender division of careers within the family by encouraging more fathers to take advantage of parental leave schemes.

Motivation

Many women have worked full-time for decades, and for many years women have outnumbered their male peers at universities in most OECD countries. Nevertheless, women are still under-represented in executive suites and board rooms. In 2024, women made up 35% of board members of EU publicly listed companies. This figure has sharply increased during the last twenty years from only 9% in 2003 [1]. However, if women are as qualified for entering management as their male counterparts, the low female share of board members reflects a huge loss of talent and educational investment to both individual firms and the economy. Fairness and equal opportunity issues also argue for political regulation and affirmative action policies.

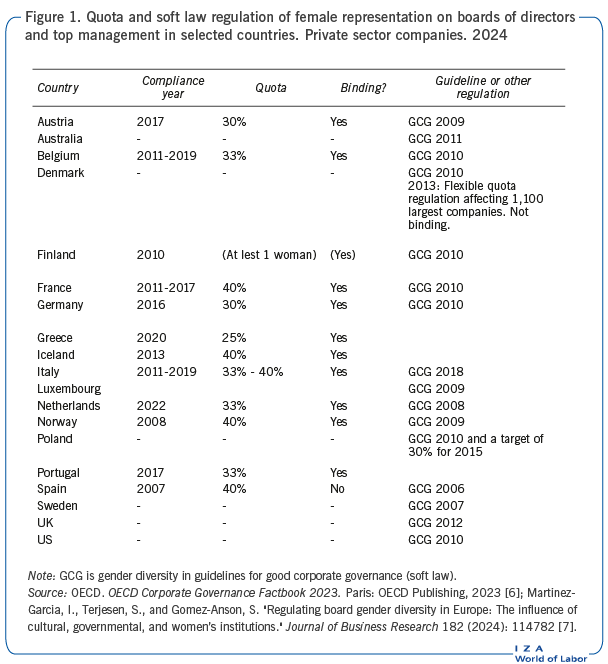

Since 2005, several European countries have introduced gender quota regulations for their largest and listed companies. From mid-2026, all large, listed companies in EU countries have to comply with a binding gender quota stated in the EU directive on Gender Balance on Corporate Boards. The Directive sets a target of 40% of the underrepresented sex among non-executive directors and 33% among all directors.

While the main political arguments for quotas are based on fairness and equality of opportunity, this article takes an economic perspective. It discusses the economic theory and empirical research on the potential effects of gender diversity at the board level and the relationship between gender diversity and firm performance. Norway, which was the first country to introduce binding quotas, receives special attention for its regulation, in force since 2008, requiring that the boards of publicly listed companies have at least 40% female representation. Many countries have followed and implemented similar regulations for various reasons.

Discussion of pros and cons

Theoretical arguments of gender diversity on firm performance

There are several theoretical arguments arguing for a more gender-balanced composition of executive and supervisory boards.

First, there is the talent pool argument for economic efficiency. If only men are viewed as potential candidates for the board, but men and women are equally qualified, boards will be of lower quality than if the best men and women were selected. Board quality is taken to be reflected in the organization's efficiency and productivity, so a larger pool of potential candidates for top positions will have a positive economic effect.

Second, diversity could improve the quality of the decision-making process compared with a more homogeneous board. Women directors might add new perspectives to board discussions or—in some firms—have a better understanding of the market than men do. A more gender-diverse board might also improve a company’s image and legitimacy, with positive effects on firm performance and shareholder value. Also, boards with a more balanced gender distribution may act more independently than all-male boards, particularly when a board is closely allied to the executive through an “old boys’ network” [2].

Another argument is that gender diversity on board of directors may have positive spillover effects on the diversity in the executive management if female directors have the resources to affect the composition of the executive board. Further, women in top management positions, either non-executive directors or executive board members, can act as role models and mentors, with a positive impact on the career development of women at lower levels. This may in turn contribute to further improved firm performance.

However, gender diversity may also have negative effects on firm performance. Assuming men and women have different opinions, a more gender-diverse board might experience more disagreement and conflict. This may result in long, drawn-out discussions—a serious problem when a company needs to react quickly to market shocks. There could also be communication problems if the executives of the company are reluctant to share key information with demographically dissimilar directors, which could compromise board efficiency [2].

The theoretical arguments on costs and benefits take on an extra dimension when quotas are binding. If a company already has an optimal board composition, imposing a binding quota for a larger share of women will alter the board composition to one that is no longer optimal. Another argument against quotas is that in many countries the proportion of women in top executive positions is low—though growing—so there is a limited pool of female candidates with executive experience. Until the pipeline widens, companies will overburden the small number of qualified women or accept less experienced candidates.

Soft and binding quota regulations

In many countries, gender diversity is encouraged but not required. Gender diversity sometimes has the status of “soft law,” such as featuring in the guidelines on good corporate governance. Such an approach relies on social pressure to generate change. Since such guidelines are not always followed, the effect is weaker than mandatory regulation with sanctions for non-compliers [3], [4]. More and more countries have introduced the topic of gender diversity in the national guidelines for good corporate governance during the last twenty years. A smaller number of countries have introduced binding gender quotas on the board of directors, see Figure 1. In 2024, ten European countries have binding gender quotas.

Also in the US, Nasdaq introduced a policy in 2022 that at least one woman should be on the board of directors or a mandated explanation. However, the US court overturned this rule by the end of 2024.

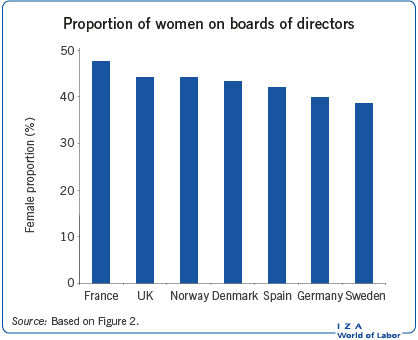

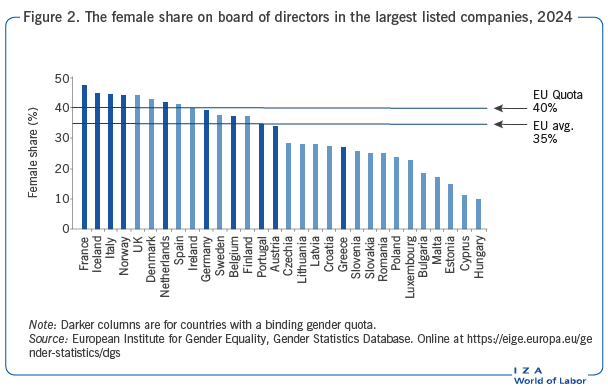

Figure 2 shows the female share on boards of directors in the largest listed companies in European countries. In quota countries like France, Italy, Norway, and Iceland, the female shares of the largest listed companies are now close to 50%. At the other end of the spectrum, several mainly Eastern and Central European countries have a much lower female share on their boards of directors.

Norway recently expanded their gender quota for corporate boards to private limited liability companies. If a firm has more than 30 employees or an operating and financial revenue cumulatively exceeds NOK 50 million, they are affected by the quota.

Until recently, the executive managers have only been subject to soft quotas. To improve the efficiency of their board quotas, France and Germany put the first binding quotas for executive management into force in 2021. In France, companies with more than 1,000 employees need to reach 30 % women among executives in 2026 and 40% by 2029 [5]. In Germany, publicly traded companies must have at least one woman and one man in an executive board with more than three members.

Empirical findings of diversity on firm performance

In the debate on affirmative action and gender quotas, claims are often made that gender diversity has a positive effect on the bottom line. However, the empirical research on the economic efficiency impact of gender diversity on corporate boards does not give clear answers. Some studies show a positive effect of gender diversity, whereas others find negative outcomes. The reasons suggested for this ambiguity include:

Variations between countries and between types of firms could mean that having more women on the board is advantageous in some circumstances but not in others. For instance, institutional differences between companies can affect the role of the board. Some studies have focused on large publicly listed companies, while others have included small and medium-size companies, which are often family owned.

Many studies show a positive correlation between the proportion of women on a board and firm performance, but correlation does not prove causation or provide evidence of its direction. It might not be the presence of women that improves performance, but rather better performing companies that choose to appoint more women. Companies might have another shared characteristic (observable or unobservable) that leads to better performance and prompts them to improve gender diversity. When researchers allow for other observed characteristics, the positive relation found in the simple models often disappears. Further, outcome measures differ. Some studies focus on economic performance measures, while newer studies also consider whether gender diversity affects board decisions and processes.

The results from studies of gender diversity on firm performance cannot directly be transferred to questions relating to the impact of gender quotas on corporate boards. The impact of gender diversity in a country with no quota regulations and a low proportion of women on boards is likely to be very different from the impact in countries with a binding quota. Boards in countries with a binding quota of 40%, for example, may have to recruit women with a much broader and potentially less qualified background compared with boards in countries with no regulations.

Empirical findings of diversity on board processes

More studies focus on work processes and decision-making on corporate boards, looking at whether boards operate efficiently rather than at how boards affect an organization’s efficiency.

Board members and chief executive officers (CEOs) of Norway’s largest listed companies and private firms were surveyed in 2006, before the 40% quota was fully implemented [8]. The survey tested a number of hypotheses about the impact of women on decision making. Women with nontraditional professional experience (those who have not held senior management roles in commercial companies) were found to have a weak impact on board decisions. Women with strong ethical and moral values were found to have a strong impact. In cases where a male majority on the board considered the female appointees less qualified, the women had significantly less impact in the boardroom. Finally, more women on boards increased the board of directors' involvement in the company's strategic decisions.

A 2009 study of US corporate boards found that boards with a larger percentage of female members had better attendance rates: having women on a board improved the attendance of men. Gender-diverse boards were found to be tougher in monitoring management and more prepared to fire the CEO when company performance was poor. Firms with diverse boards often included incentive schemes in management compensation packages. Overall, the researchers concluded “that diverse boards add value in firms with otherwise weak governance” and that female board members might be too tough (and over-monitor) in firms with otherwise strong governance [2], p.308.

Evaluations of the impact of quota regulations on firm performance

Several recent research papers have analyzed the impact of these quotas, either in a country-specific setting or as meta-analyses or cross-country studies. Some of the effects of gender quotas may take time, maybe many years, before the full impact of gender quotas has materialized. Therefore, some of the effects found in the existing studies may be considered short- or medium-term effects, and the long-run effects of quotas may be more positive (or potentially negative) than what is found in the existing research.

In this respect, the Norwegian evidence is interesting because Norway has had a gender quota experience for over 20 years. In 2002, less than 10% of board members in the largest publicly listed Norwegian companies (known in Norway as Allmennaksjeselskap, or ASA companies) were women. Regulations introduced in 2002 gave those companies five years to raise the proportion of women on their boards to 40%. By January 2008, women made up more than 40% of the board members. In that sense, the law was a clear success.

A large number of research papers have studied the Norwegian quota. Some of the first studies which included observations on the first years after the quota was in force in 2008 have found a significantly negative quota effect on a number of performance variables and an immediate negative market reaction for all companies which were subject to the quota regulation. Further, it was first found that the Norwegian quota prompted companies to delist from the Norwegian stock exchange to avoid the quota obligation. However, more recent and more detailed research has criticized these findings [9]. According to this research, there is no evidence that the Norwegian quota affected the performance or the value of the firms which were subject to the quota. The argument that the quota prompted the companies to delist is also rejected [9].

The Norwegian minister who sponsored the law made it clear that the longer-term objective is to have a better gender balance in senior management, achieved through longer term diffusion or spillover effects rather than through quotas, as more women assume positions of executive responsibility. The law achieved its short-term objectives—increasing the number of women on boards and reducing the power of the “old boys’ network.” However, so far, the diffusion effect has been weak.

The longer-term spillover effects of the Norwegian quota are analyzed in a more recent study [10]. The results are not that optimistic, in the sense that, besides affecting female representation on boards subject to the quota, there have been no observed spillover effects of the quota on the Norwegian labor market. The quota regulation has not yet reduced the gender gap in management positions in any significant way. Further, the quota does not seem to have affected young Norwegian women’s career aspirations, career plans, and behavior, which may have consequences for the future pool of potential directors on Norwegian boards and top executives. The study concludes that “Overall, seven years after the board quota policy fully came into effect, we conclude that it had very little discernible impact on women in business beyond its direct effect on the women who made it into boardrooms” [10], p.191.

Since there are now a number of countries which have introduced binding board quotas, empirical evidence on the impact of these quotas has been steeply increasing [4]. There are a number of country-specific studies, mainly analyzing the short-run effects of the quotas on firm performance and the female share on board of directors. The results from these studies are mixed.

In this review, the focus is on two recent studies which summarize the empirical evidence on a more overall level: A meta study which collects and systematically summarizes all the empirical evidence from country specific analyses [3] and a cross-country study which estimates the quota effect based on data from all European countries [4].

The later study summarizes their findings based on 51 studies on the effects of gender quotas on firm performance, stating that “34% of the estimates are significantly positive, 21% are significantly negative, while almost half of the estimated effects are insignificant“ [4], p.7. They find more negative effects on stock market returns and mainly positive effects on board competences and—not surprisingly—female representation on board of directors. Finally, the results from this study indicate that soft law (non-binding quotas or guidelines on good corporate governance) is much less influential than binding quotas.

The other study estimates the impact of gender board quotas on the female share among non-executive directors, CEOs, and other executive directors based on BoardEx data covering the period 1999-2023 [3]. The data includes the largest listed companies with a stock market capitalization of more than € 200 million, i.e. the sample also includes many (smaller) listed firms which are not subject to quotas regulations even if the country of the firm has a quota regulation. This allows the authors to estimate whether the quota regulation has spillover effects to other firms not subject to the quota. The study finds that quota regulations have increased the female share among non-executive directors by 8.4 percentage points [3]. The most prominent effects are found for the highest binding quotas (40%) where the effect is 13.4 percentage points. Although soft law policies have a much smaller impact on the female share of non-executive directors, only about 2 percentage points, the female share of board of directors has increased in countries without binding quotas. The study also analyses the impact of quotas on CEOs and other executive board members. Here the results are insignificant, implying that the quota regulations have not significantly impacted the share of females among top executives.

Spillover effects of quotas?

The long-term spillover effects of quota regulations are key when evaluating the overall effects of board quotas. This was already stated by the Norwegian minister who introduced the quota discussion in Norway in 2002, and this has been the underlying argument for the quota regulations that more women on board of directors will have spillover or trickle-down effects to the executive board and further down in the company. The research indicates positive spillover effects to lower levels in the organisation from having female board members: There seem to be a smaller gender wage gap and occupational gap at lower levels in the company [11].

However, when analyzing gender quotas on board of directors, the key link is the link between the female share on board of directors and the female share in the executive board. One study indicates that this link is weak—there seems to be an insignificant relation between the female share on board of directors and the female share on the executive board [3]. According to the EIGE database [1], the female share of CEOs in the largest listed firms is 8.5% in the EU countries and less than 10% even in the countries with board quotas for many years. In Norway, the female share among CEOs is 15% in the largest listed companies.

The key question is whether women on board of directors matter for gender equality in the executive suite and thus further down in the organization? Of course, changing the number of women in the boardroom will not affect decisions of the board and the operation of the company unless the female directors actually have influence. “For gender diversity to have an impact on board governance, it is not sufficient that female directors behave differently than male directors. Their behavior should also affect the working of the board” [2], p.297.

A number of studies have argued that only one woman on the board of directors does not change much with respect to spillover effects to executive boards or the gender gaps in general. Only one woman on the board will be a token woman. Other studies have focused on a critical mass of women, typically around 33%, as the necessary share of females in order to have an impact [11].

A register-based study covering all Danish private sector companies with more than 50 employees from 1995 to 2019 found that even one woman may significantly impact the female share in the executive board. The estimated effect is, however, small and more detailed analyses indicate that the effect fades over time, mainly because women in the executive board seem to exit more quickly from the positions in the executive board [11]. Formal competences are also necessary for female board members to have an impact in the boardroom. Influential female board members are typically women with a background of being CEO or executive board members in other companies, they have a strong professional network from their past employment experience, especially a network to other influential male board members [11], [12]. In this sense, the studies indicate a catch-22: In order to impact the gender gaps in the companies, there need to be powerful women in the board of directors. Powerful women have powerful networks because they have previously been CEOs or board members. They are known and visible by other board members and nomination committees who appoint new board members. According to two studies, board quota regulations do not seem to have affected the female share of CEOs or other top executives [3], [11]. This implies that for the gender board quota to improve gender diversity at the executive level effectively, it must be coupled with other policies.

Norway was the first country to implement a binding gender board quota. It is also a Nordic country with family-friendly employment regulations in place. Such regulations are often said to help women advance their careers. The Nordic countries have a long tradition of such laws, including encouragement for fathers to take parental leave. Still, the family-friendly policies alone were not substantially helpful in increasing the number of women in director or top executive positions. For example, long periods of maternity leave are intended to enable women to continue their careers after having children, and virtually all mothers take such leave. These provisions seem to have had an unintended boomerang effect. Studies show that children are an important explanatory factor for the divergence in men's and women's careers, even when controlling for level of education. In the Nordic countries, apart from Finland, women also take part-time positions to a large extent, which generally do not lead to top executive positions. Besides the direct negative effects on experience and human capital of taking long parental leave and part-time work, there may be more subtle effects on gender norms and stereotyping, especially when women avail themselves of parental leave more frequently than men do. Such indirect discrimination could disadvantage highly skilled women who aspire to top executive careers, preventing spillovers from the gender quota.

In response to the low spillover effects of the board quotas, France and Germany implemented similar quotas for the executive level. The law in France seems to have increased the number of women among executives in the short run. Whether this complement diversity quota will have effects other than the immediate increase of women executives is too soon to be evaluated. The policy may, for example, change the demand for qualified and experienced women or inflict a demographic change in the selection of women (and men) who become executives. Given higher exit rates among executives, these complement quotas for executives may lead to high turnover among female executives, making them possibly less influential than their male peers. Moreover, corporate top executives are still a small group, and it is unclear whether a quota policy for that level will spillover to other parts of the labor market. If the complementary policies targeted the research-identified reasons behind the higher exit rates among executives, such as firm culture, gender norms, and expected long continuous working hours on the general labor market, it may have spillover effects on the rest of the labor market. Learning from the Nordic countries, family-friendly policies may bring adverse consequences from a gendered labor market perspective. But, if a policy raised the share of parental leave taken by fathers in these firms, the life-course conditions for men and women may become more equal. This may in turn change the gendered work norms. Pressures from investors may also bring about such a change [3].

Limitations and gaps

Although a growing field, there is yet no consensus on the best methods for analyzing the impact of gender diversity on firm performance. In general, it is difficult to overcome the endogeneity of diversity in performance estimations. The conclusions outlined here are based on evaluating the most statistically robust studies and results. Furthermore, most results reflect only the short-term effects of gender quotas. Although they provide the most solid statistical validity, results from evaluating gender quotas may not be generalizable to countries without such a quota. However, in the longer term, quotas in some countries may bring about change in other countries. Also, there may be more positive performance effects if the quota regulation brings about deeper-rooted changes.

Summary and policy advice

Research offers no clear answer on whether gender diversity on boards of directors positively affects economic efficiency and firm performance. The empirical results are sensitive to statistical specification and need to be weighted by their statistical validity. When the results are weighted, positive economic efficiency effects of gender diversity on corporate boards generally cannot be documented. For weakly governed firms, having more women on the board positively affects firm performance. Here, an explanation may be that women tend to be stricter monitors of board members to improve board decision-making processes.

Despite the intention of many board quotas, current research implies that they have little or no influence on gender diversity at other levels of the organization. The adopted EU legislation requiring corporate boards to have at least 40% non-executive and 33% executive members by 2026 may not alter gender diversity among CEOs, other top executives, or middle managers.

Board quota experiences from the earliest example of Norway to the recent introduction of quota laws in other European countries, show little effect on other decision-making levels of the organization. Specifically, the number of women in top executive positions is still low. Given that women have higher exit rates from top executive positions, it is not only a question of gender gap in recruitment but also of retention. The new executive quotas in France and Germany will increase the number of women executives. Still, the larger exit rates of women executives may make these policies less effective in bringing about change at other levels of the organization. The key question becomes how the gender gap in management positions can be alleviated in a sustainable way?

The higher exit rates among female executives compared to their male counterparts may be attributed to firm culture and gendered work norms. If the main policy objective is to encourage more women to enter and remain in decision-making positions in private companies, policymakers may need to shift their focus to addressing the underlying causes, including promoting a more equal division of career and family responsibilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 3 of this article adds recent evidence from ten quota countries, updates figures, and adds new Key references [1], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [9], [11], and [12].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Nina Smith and Emma von Essen