Elevator pitch

While many firms have recognized the importance of recruiting and hiring diverse job applicants, they should also pay attention to the challenges newly hired diverse candidates may face after entering the company. It is possible that they are being assessed by unequal or unequitable standards compared to their colleagues, and they may not have sufficient access to opportunities and resources that would benefit them. These disparities could affect the career trajectory, performance, satisfaction, and retention of minority employees. Potential solutions include randomizing task assignments and creating inclusive networking and support opportunities.

Key findings

Pros

When employers have more information about each worker’s past performance, they are more likely to give women proper credit for their contributions to group tasks.

Well-specified rubrics can reduce the bias that arises from subjective evaluations.

Employers can randomly assign mundane tasks to employees so that no one is favored.

Employers can pay attention to how inclusive their networking events are and create affinity groups to make minority workers feel included.

Cons

Women may be given less credit for group work than men when it is unclear what each person contributed, which could affect their chances of being promoted.

When subjective ratings are used, biased employers may not weigh objective measures of performance the same for black and white employees.

Women are more likely to be asked to complete mundane tasks than men.

Minority workers may not have the same networking opportunities that nonminority workers do, which could affect their earnings and career trajectories.

Author's main message

Employers risk the possibility of negating any benefits from policies introduced to hire diverse employees if they ignore the challenges that these individuals encounter after joining the company. Firms should be conscious of existing policies and traditions that provide advantages for some but not all employees. Promoting affinity groups and paying careful attention to what tasks minorities are assigned to can help improve the work environment for minority employees and should be strongly considered by any employer with a diverse workplace that wants to retain and support minority employees.

Motivation

As more attention is paid to how some individuals face unfair disadvantages because of their identity, employers and employees are increasingly questioning whether their workplace is equitable. For example, Facebook was federally investigated in 2020 due to accusations of racial bias in hiring. In countries like the US, it is illegal to discriminate in the hiring process based on a person's race, gender, or sexual orientation. Consequently, firms that discriminate risk engaging in costly litigation as well as tarnishing their public image. There are also non-legal reasons why a firm would be interested in making sure its workforce is diverse. For instance, firms may value the different perspectives and talents that come with having employees from different backgrounds.

The topic of labor market discrimination has been studied by economists for decades. Primarily, this research has focused on discrimination at the hiring stage. For many of these studies, the researchers create fake applications and submit them to real job postings. The applications are designed to look nearly identical; however, some of the fake applicants’ characteristics (e.g. gender) are purposely changed. The aim is to see if there is any difference in callback rates between the fake applicants based on the changed characteristic. If there is a difference, it cannot be explained by differences in factors like work experience or educational attainment because these are qualities that the researcher kept constant across applications. This allows researchers to conclude that employers are discriminating based on the characteristic that was changed. One of the seminal studies that uses this method found evidence of discrimination against black applicants when the researchers sent fake applications to job postings in Boston and Chicago in the US [2]. Another study, conducted in Austria, also uses this technique and found evidence of discrimination against lesbians who are open about their sexual orientation who applied for clerical and accounting positions [3].

If employers only focus on eliminating discrimination at the hiring stage, they may increase the number of new minority employees they recruit, but may miss other issues minorities face after they are hired. These issues could relate to evaluations, task assignments, networking, and work climate. Not addressing issues of disparities or discrimination could have major repercussions on the behavior of employers and employees.

From the employer's side, unwarranted differences in how employees are treated could cause firms to fail to promote or even fire minority employees harmed by this unequal treatment. For instance, if women are systematically rated worse than men on performance reviews, then women may be seen as less productive or be viewed as having less potential relative to equally capable men. This could then result in women having slower career progression or shorter tenures than men. Consequently, employers could negatively affect minority employees’ positions in the firm if there are biased procedures or work experiences.

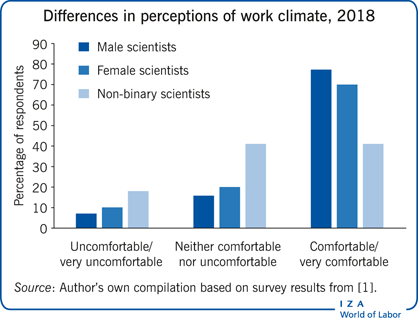

From the perspective of employees, several studies find a connection between discrimination, job satisfaction, and thoughts about quitting. One of these studies uses data from Finland and finds that employees who experience discrimination in the workplace express higher job dissatisfaction and are more likely to have searched for a new job in the last month [4]. In addition, several scientific organizations published a report based on a survey they conducted of LGBT+ physical scientists in the UK and Ireland [1]. They found that 28% of their LGBT+ respondents said that the workplace climate or discrimination toward LGBT+ individuals caused them to think about leaving their jobs at some point. Therefore, minority employees who do not feel like they are treated fairly may voluntarily leave the firm.

Even if employees choose to remain at the firm, they may change their behavior based on their experiences and expectations. For instance, if women believe that supervisors will not properly recognize their work on a particular task the same way they would for male employees, they may change what tasks they undertake. If they switch to a task they are not as good at or that could be handled better by someone else, then this is inefficient. It could also be inefficient for the firm if female employees lose motivation to pursue certain tasks because they are not sufficiently appreciated for working on them.

If employers are spending time and energy trying to recruit diverse workers, then they should also care about retaining these workers and keeping them motivated so that hiring efforts are not wasted. This requires employers to pay attention to how their minority workers may face different work conditions than their nonminority counterparts and consider policies that can reduce any differences that prove harmful.

Discussion of pros and cons

Differences in promotions and raises

If firms make decisions about promotions and raises on an employee-by-employee basis (i.e. in contrast to, for example, a firm-wide raise given to all employees who have worked at the firm for a certain number of years), then there is the potential for an employee's personal characteristics to influence the firm's choices. In fact, existing literature has shown that promotion rates do differ by an individual's race or gender, even when comparing employees with similar performance levels. One study analyzes data about newly hired employees in the US and finds that men are more likely to be promoted than women, even when employees’ age, tenure, education level, occupation, and performance evaluation scores are held constant [5].

There are several reasons why some groups may receive promotions and raises at a lower rate than others despite being equally productive and qualified. Decision-makers could hold a bias against or in favor of individuals from a particular group that affects how they assess employees. It is also possible that employees from some groups may be granted opportunities (e.g. to network) or have different experiences at work (e.g. being asked to do tasks unrelated to their skills, or being the target of derogatory language) that affect their performance, which in turn impacts their evaluations and the decision-maker's opinion of them.

Differences in assessments and evaluations

If unaddressed biases and stereotypes affect how evaluators rate employees, then this can impact decisions about who keeps their jobs, who gets promoted, and who receives a raise. Consequently, employers may hire a notable number of minority employees but hold a misperception that they are underperforming. If some of these employees are then fired, minority retention rates may be low because they are judged unfairly.

One study looks at how colleges in the US evaluate professors based on their publication history [6]. In academia, professors can pursue projects independently and publish solo-authored papers. Like for many industry positions, professors may also work on projects in groups, which would result in co-authored papers. At most universities, when professors are at the beginning of their careers (i.e. assistant professors), these papers are assessed by others to help determine whether they should be promoted. With solo-authored papers, there is no confusion as to what the professor contributed to the project. On the other hand, with co-authored papers, it is unclear what role each scholar in the group played, so evaluators must make assumptions about how much work the professor under review contributed. The abovementioned study finds that a co-authored paper has a larger positive impact on promotion for men than women, even when controlling for the total number and the quality of the publications [6]. This suggests that academics judge men and women's co-authored work differently and give men more credit for joint work than they do women.

The study also includes a set of experiments designed to test further whether evaluators assume men contribute more to group work than women do [6]. In the first experiment, workers were recruited to complete two similar quizzes. Both quizzes were either stereotypically male (i.e. two mathematics quizzes) or female (i.e. two grammar quizzes). Other individuals were recruited to act as evaluators. Evaluators were told information about the first quiz score of a randomly chosen male and female worker, and their task was to guess how well these workers did on the second quiz.

Some evaluators were told the Quiz 1 score for the male worker and the Quiz 1 score for the female worker. These evaluators guessed that men and women correctly answered a similar number of questions on Quiz 2, regardless of whether the workers completed the stereotypically male or female quizzes. Other evaluators were told the combined score of the male and female workers and thus did not know how well each of them did individually on Quiz 1. For the stereotypically female quiz, evaluators predicted that men and women performed similarly on the second grammar quiz. However, for the stereotypically male quiz, evaluators guessed that women answered fewer questions correctly than men. This suggests that when they saw the joint Quiz 1 score, they assumed men contributed more to that sum than the women did. Notably, this was not the assumption they made when they saw individual Quiz 1 scores. In short, when men and women work on tasks as a group, evaluators may give less credit to women than men, especially if the task is seen as one in which men typically perform better.

Another study analyzes data from a firm in the US that includes information about employee race and productivity [7]. Supervisors rated how well the firm's salespeople performed every year on a scale from satisfactory to outstanding. There was also data on how close each salesperson was to meeting their annual sales goal, a measure that is more objective than the supervisor's rating. The study finds that black employees received lower ratings than equally productive white employees. Furthermore, while the study has a limited number of observations to analyze, the researchers did find evidence that white supervisors rated black employees lower than white employees, even when controls were added for objective performance. At the same time, black supervisors rated white employees lower than white supervisors rated them. Therefore, subjective measures of performance could be affected when an employee and supervisor do not share the same race. If supervisors are more likely to be from the majority racial group, then this could be particularly harmful to minority employees.

Differences in types of tasks assigned and completed

As discussed above, employees with the same position may be evaluated differently because of biases. This difference in evaluations could also occur if workers with the same job title are completing different types of work. For example, one worker may be asked to complete basic tasks like setting up the conference room more often than others. Tasks like rearranging a room before a meeting or making coffee may be tasks that need to be done and that contribute to the company's effective operations, but they are relatively trivial and prevent an employee from working on a different task that would better utilize their talents. More importantly, no one will be promoted or given a raise for brewing the perfect pot of coffee, but they might if they are able to complete tasks that are challenging and showcase their specialized skillset. For this reason, it is important that basic tasks are not assigned to or taken up by one type of employee more than another.

A study conducted in the US examines who is likely to be asked to perform tasks that anyone can complete but benefit the group more than the individual [8]. The researchers call these “low promotable tasks.” They find that both men and women are more likely to ask women to complete these low promotable tasks than men. This result appears to be driven by the correct belief that women are more likely to accept these requests than men.

If every employee works for the same number of hours, then minority employees might spend less time on complex tasks than nonminority employees. Meanwhile, nonminority employees will have more opportunities to sharpen their skills as they continue to complete challenging tasks. Consequently, minority employees may not be evaluated based on the same distribution of tasks and may miss opportunities to grow professionally.

Even if the disparity in task assignment has no effect on career progression for minority employees, it could affect their job satisfaction in multiple ways. A 2009 study finds that employees who feel neglected (e.g. they do not consider their work productive) are more likely to attempt to search for other job opportunities compared to employees who do not feel neglected [4]. Additionally, employees who believe they receive unequal treatment are more likely to report searching for another job in the last month and are more likely to have a new job within four weeks. Thus, if an employer tends to delegate basic tasks to minority employees more than majority employees, this could lead minority employees to feel discontent and look elsewhere for employment.

Differences in networking opportunities

While part of an employee's professional success may relate to their performance on tasks, part of it may also depend on their relationship with others. Having an extensive network can help employees in multiple ways. Members in an employee's network can act as advocates, supporters, and sources of valuable information who can open doors and provide guidance in ways that the employee could not achieve alone. As such, if one group of employees is given more networking opportunities than another, then the latter group may find themselves at a disadvantage for reasons that are independent of their own performance.

One study conducted at the University of Essex recruited participants to complete experiments to determine whether men and women network differently [9]. Men and women did not have significant differences in the number of connections they made. However, there is evidence that men and women benefit from and respond to these connections differently. Men are more likely than women to promote and give higher earnings to individuals with whom they have interacted, and men tend to interact with more men than women. Men are also more likely to promote the person who has previously promoted them, forming a type of reciprocal relationship. These factors contribute to gender gaps in earnings and promotion rates.

A study of executives and non-executive board members from the US, UK, France, and Germany finds that men within this group earn over $70,000 more than women, on average [10]. Even when the researchers account for differences in age and education, men earn more. They find that the more influential people a male executive meets, the higher his salary. The number of influential people a female executive meets, on the other hand, does not significantly impact her salary. Interestingly, neither salaries nor the impact of professional connections on salaries differs significantly between male and female non-executive board members. Therefore, if an employee's earnings and professional advancement are impacted by their network, then employers interested in diversity and equity should pay attention to whether or not minorities have the same networking opportunities as their nonminority colleagues.

Work climate

Job satisfaction has been connected to whether employees remain at their current jobs [4], and part of job satisfaction may depend on how comfortable employees feel at work. The aforementioned survey of LGBT+ scientists finds that a hostile workplace can cause employees to consider leaving, and shows that employees’ perceptions of the work climate can vary by identity, as seen in the Illustration [1]. Working in a place that is not welcoming could affect an employee's performance, too. This, in turn, could negatively impact their evaluations and chances for advancement.

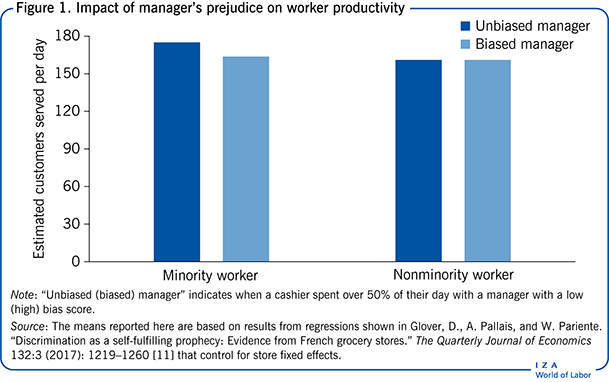

Even if employees choose to stay at a firm that appears not to value diversity, their performance may be affected. One way this can happen is if supervisors are biased. This is shown in a study conducted with cashiers at French grocery stores [11]. Managers completed a test to determine how strongly they associated North African names with poor performance, which was used to measure their bias against minority employees. Minority cashiers scanned items more slowly, took more time to finish checking out customers, and were absent more often when biased managers were on their shift compared to when non-biased managers were around.

Figure 1 shows how minority cashiers checked out fewer customers when they spent most of their shift with a biased manager compared to an unbiased manager and reveals how workers may not perform efficiently when they are working with prejudiced managers. This drop in productivity appears to be partly because biased managers do not interact with minority employees as much. If minorities notice this, they may decide to exert less effort because biased managers will not pay attention to them.

Relatedly, psychologists have studied the phenomena of stereotype threat, which occurs when someone receives a cue about their identity and the negative stereotypes associated with their identity before performing a task related to the stereotype. The consequence is that the individual's performance on the task could suffer, which could be because the individual gives in to the stereotype or is overly anxious about confirming it. In several studies, researchers have found that black students’ scores on a verbal test decrease if they are subtly primed to think about the negative stereotype that black people are not as intelligent as white people before taking the test. These studies have been primarily conducted at predominantly white institutions. One recent study finds that the test scores of black students are not affected by this cue when the black students are from a historically black college, suggesting that the environment could influence how minorities respond to these types of threats [12].

Limitations and gaps

Each employee and employer is different. For this reason, research findings on bias and discrimination in the workplace can be mixed, and solutions that work at one firm or industry may not be effective in other contexts. Countries have different laws, social norms, cultures, and histories that could influence how diverse employees are treated as well as how effective diversity-related policies are in practice. Even within the same multinational firm, research has found that employees in different countries can face different challenges. For example, gender differences in promotions and beliefs about women's role in the workplace may be different based on the office's location. Consequently, diversity issues and their appropriate solutions may vary based on the country. Context matters, and employers should not expect that they will reproduce the same results as another firm even if they perfectly mimic that firm's interventions or policies.

Additionally, it should be noted that early studies on stereotype threat have received skepticism. Regardless, the issues mentioned in the sections above are meant to describe possible situations when an underrepresented employee may experience inequitable treatment. Not every employer or employee will necessarily face the same problem areas. Furthermore, employees’ preferences and time demands could have an influence too, but are not discussed here.

Moving forward, more studies on workplace bias should be conducted that focus on identities besides race and gender, which are the main characteristics examined in the current literature. Employees have different religious backgrounds, sexual orientations, and disability statuses, among other characteristics. It would be presumptuous to apply what studies have learned about employees of different races and genders to other underrepresented groups without conducting further research about these groups.

Summary and policy advice

Upon entry, minority employees may face challenges at their new workplace that could cause their paths to diverge from their nonminority colleagues. Opportunities for promotions and raises could be negatively affected by biased evaluation processes, disparities in task assignment, differences in networking, and unwelcoming work environments. These factors could also affect employees’ job satisfaction, desire to continue working for their employer, and performance. Recognizing these challenges is the first step for employers concerned about retention rates among their minority employees.

Subjective measures of performance may not perfectly reflect an employee's objective productivity. Subjective ratings allow evaluators’ biases to influence their assessments. Creating well-specified rubrics and using standardized questionnaires are two ways to try to discourage this from happening.

To ensure that assignments are not given based on worker demographics, employers should pay attention to the types of tasks employees are completing. For mundane tasks, employers could implement a rotating schedule where each employee is asked to complete the task once before anyone is asked twice. Alternatively, the task could be randomly assigned [8]. Either of these strategies would reduce the chances of certain employees being disproportionally asked to perform such tasks at the expense of working on tasks that would better showcase or improve their skills and help them advance their careers. Importantly, employers should avoid asking for volunteers for these basic tasks because a study has shown that women are more likely to volunteer for low promotable tasks than men are [8].

Making networking opportunities equitable is a challenge. Some employees may be more sociable, personable, or outgoing than others, which may cause mentors and influential colleagues to gravitate toward them naturally. Instead of trying to change people's personalities, employers may want to focus on ensuring that the networking opportunities they organize are inclusive. If a firm wants to organize an informal gathering, they can plan some gatherings during lunch breaks so that those with time conflicts in the evening (e.g. parents picking up their children from daycare) can attend. Try to avoid scheduling any of these events during religious holidays. Ensure that the invitation is widely distributed (e.g. via email to all employees) and do not rely on word-of-mouth, which may unintentionally cause some employees to be left out. The aim should be to provide everyone with a chance to build professional connections, with the understanding that the employee will need to be proactive in order to develop these connections. Formal mentoring programs could also be introduced.

For employers wishing to change perceptions of the work climate, several actions are available. Inclusive social events, as mentioned above, could make a positive difference. They may also consider creating and financially supporting affinity groups, where employees who share an identity can have meetings, host events, and have discussions. For example, Amazon has several affinity groups, including Amazon People with Disabilities, Black Employee Network, and Body Positive Peers. Such groups can foster a sense of belonging and provide support systems for minority employees.

While there are many ways that employers can try to reduce inequities in the workplace, they should be aware that some approaches may be more effective than others. For instance, a 2006 study analyzes whether seven approaches (including, diversity training, networking programs, and mentoring programs) have an effect on the share of white women and black people in management positions [13]. Approaches that involve goal-setting and oversight, like diversity task forces, are effective at increasing diversity. This may explain why universities have begun hiring deans and chancellors of diversity, equity, and inclusion and why companies like Microsoft and Walmart have Chief Diversity Officers. The study also finds evidence that mentoring and networking programs are useful, but they do not help everyone [13]. Networking benefits white women while mentoring aids black women. Interestingly, although nearly 40% of the sampled employers made use of diversity training in 2002, diversity training did not significantly improve the share of white women, black women, or black men in management positions. This is consistent with related work that has found that diversity training may not lead to changes in actions to the degree that might be hoped for. Therefore, employers may want to focus their initial efforts on developing one or more teams of dedicated individuals who would be placed in charge of developing, enforcing, and/or evaluating diversity-related initiatives.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Ernesto Reuben and Jack Mills. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [12].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Mackenzie Alston