Elevator pitch

In today's globalized world, people are increasingly mobile and often need to communicate across different languages. Learning a new language is an investment in human capital. Migrants must learn the language of their destination country, but even non-migrants must often learn other languages if their work involves communicating with foreigners. Economic studies have shown that fluency in a dominant language is important to economic success and increases economic efficiency. However, maintaining linguistic diversity also has value since language is also an expression of people's culture.

Key findings

Pros

Economic well-being is enhanced when members of a group communicate in the same language.

Learning a dominant language is an investment in human capital.

There are important financial benefits to members of linguistic minorities who learn the dominant language; those who use their native language do not experience such benefits in the labor market.

Because of externalities in the use of a common language, letting individuals pursue their self-interest may not lead to optimal outcomes.

The trend toward English as a common second language has some advantages and is not expected to be reversed in the foreseeable future.

Cons

Linguistic diversity has value, although some of it is non-pecuniary.

Because of the link between culture and language, the more languages that can be accommodated, the greater the welfare.

Knowing other languages can bring benefits, and linguistic diversity can increase the number and type of goods available.

Public support for a minority language is an indication that people value it and are willing to take action to maintain it.

While there has been a tendency toward language convergence globally, there is also a strong desire to maintain diversity.

Author's main message

A dominant language enables people to communicate with others in the same region or country, and having a common international language extends that ability beyond national boundaries. Learning the dominant or common language is a good investment in human capital, but people also value their native language and want to preserve it. There is a trade-off between the two objectives, but they can be pursued together if more people become bilingual or multilingual. In highly educated societies, part of the education curriculum should be to encourage the learning of foreign languages and cultures.

Motivation

More than 7,000 languages are spoken in the world [1]. The importance of some of them (such as English) is growing, but other languages are in decline and some are even threatened with disappearance (such as Atsugewi, an aboriginal language of northern California). In a group of people who have to interact with each other, using a common language makes economic activity more efficient, but some people also value another language because of the connection between language and culture. Many people argue that linguistic diversity—globally and within individual countries—should be preserved.

There is now a worldwide trend toward the use of English as a common language for international relations. Whether that is good or bad depends on how well policymakers can balance the relative advantages of linguistic uniformity and linguistic diversity. Economics, along with other social science disciplines, can provide a useful framework for investigating the policy issues and making the appropriate decisions.

Discussion of pros and cons

One line of academic research, developed over the last 50 years or so, views language as a matter of economic choice [2]. That research was concerned initially with the characteristics of a language that make it efficient for carrying information. The emphasis was on what is called the corpus of a language (such as the syntax and the grammar). However, most of the subsequent research on the economics of language has followed a different path and has been concerned mainly with the interactions between two or more languages in societies with different cultural groups or with many recent immigrants. The interest is with language status rather than language corpus. The goal is to understand how people behave in such contexts and to devise appropriate economic policies, for instance, in education and labor market institutions.

Studies have focused on the impact of language skills on earnings and other labor market outcomes, the evolution and dynamics of languages (including the disappearance of some and the domination of others), and language policy and planning in countries or regions where several languages co-exist. Several surveys have reviewed the economics of language [3], [4], [5].

Language as an economic variable

The recognition of language as an economic variable is based on four simple ideas [6]. First, reflecting the communication values of language, the economic well-being of a society is enhanced when members can communicate with each other in a single language. For example, most production activities involve teamwork and require understanding the same written and verbal instructions. Consumption activities are also facilitated by a common language, which enables buyers and sellers to understand each other. In contrast, communication in languages that not everyone understands tends to slow economic activity.

Second, there is a connection between language and cultural identity, which also influences people's decisions about the language used for communication. Pushing to the limit the argument of the communication value of languages would imply that all of humankind would be better off speaking a single language. This is obviously not what has happened, partly because the world is not yet totally globalized, but also because there is a preference in many societies for using a native language that people value because it was received from their ancestors and defines their identity. In particular, some consumption goods, such as books, songs, and television programs, have an important linguistic component. Language and culture are closely connected.

Third, language contributes to human capital and can be developed in the same way as other productive skills. People can acquire or improve their language skills by studying languages in school, conversing with others, and so forth. Many people, especially those who belong to a linguistic minority, learn new languages because they want to expand their abilities to communicate and, by doing so, be more productive and earn higher wages [7]. When deciding what languages to learn, people tend to choose a language that has the highest financial returns. Language learning, like other investments in human capital, has opportunity costs. Becoming familiar with a new language takes time and resources that could have been devoted to other activities. In a given labor market, the interaction between supply and demand will determine the amount of language learning that takes place. Supply depends on the composition of workers’ native tongues and second language skills. Demand is determined by the various production processes, the technology, and the languages of customers and producers.

Fourth, letting individuals pursue their own interests in acquiring language skills may not lead to an optimal outcome because the advantages of using a language depend on the number of other people who speak it. There is an externality in the use of languages that is not taken into account if people pursue only their self-interests. When language is viewed mainly as a tool of communication, the natural tendency is to converge toward the efficient outcome of using a single language. Some individuals may value their cultural identity as members of a group, as reflected in part by their native language, but may nevertheless decide to switch to the language that yields the highest economic value. There is clearly a policy trade-off between linguistic uniformity, which maximizes the communication value of a language, and linguistic diversity, which emphasizes the cultural characteristics of languages.

The importance and value of language learning

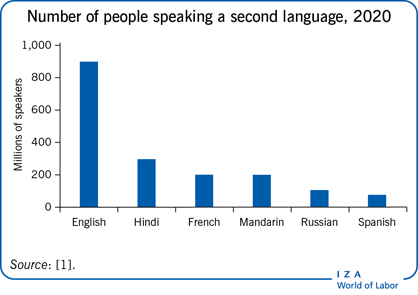

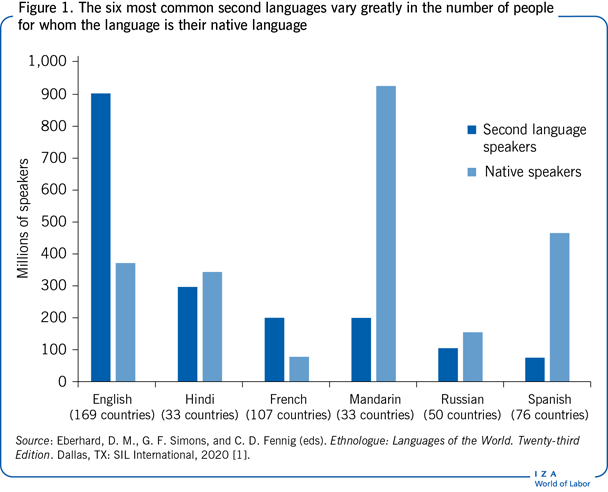

In addition to their native language, received at birth, some people decide to learn a second language. This is especially likely for people who belong to a linguistic minority, or whose native tongue is not used in national or international communication. Figure 1 depicts the number of people who speak, as a first or second language, the six languages with the largest numbers of second-language speakers worldwide, along with the number of countries in which the languages are spoken.

While Mandarin has the largest total number of native speakers worldwide (because of China's large population), English is by far the most popular second language. There is now compelling evidence that English has become a global lingua franca, a common international language of commerce and communications around the world. Mandarin (China), Hindi (India), Russian (Eastern Europe and Central Asia), and Spanish (Latin America) enjoy a dominant role in some regions of the world, but their influence is limited and they have fewer second-language speakers than native speakers. If English has any competition, it is French, which shares with English the characteristic of being used more as a second language than as a first language and of being spoken in many countries. A hundred years ago or so, French was a dominant international language, but its reach has declined substantially.

English is also a dominant language of some of the world's major immigrant-receiving countries, which include Australia, Canada, and the US. For that reason, considerable research has examined immigrants’ acquisition of the dominant language of their destination country. When immigrants arrive in a country, one of their first tasks is to learn that country's language, so that they can better integrate into the local economy.

Both the determinants and impacts of language learning in the context of international migration have been extensively researched [8]. The determinants of language learning that have been explored include exposure, efficiency, and economic incentives. The empirical evidence shows that those factors—the three Es of language learning—are important in explaining fluency in the dominant language. Exposure is related to duration in the host country, concentration of the migrant's native language within the country, and family characteristics such as the language of the migrant's spouse and whether the migrant has children. Exposure to a language, both before and after migration, makes a language easier to learn. Efficiency in learning a language is usually higher the younger and more educated a person is, and the smaller the linguistic distance (in vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation, for example) between the new language and the migrant's native language. Economic incentives are related to the anticipated duration of the stay in the new country and to expected earnings.

Many studies have also examined the labor market impacts of learning a country's dominant language. Immigrant-receiving countries have censuses and surveys that include questions on language use and skills. Respondents assess their own language skills, generally on a scale that includes two or more skill categories. Not surprisingly, a major finding of studies that examine the acquisition of these countries’ dominant language is that knowing that language brings important returns [8], [9]. Specifically, the earnings advantage is in the order of 10–20% for people who are fluent in the dominant language compared with those who are not. Similar returns are observed for learning the dominant language in countries where English does not dominate, such as in Israel and Germany. This finding suggests that immigrants adapt primarily to the situation of the national economy of their new country or residence and not just to the dominant international language.

Little research has been done on the value to immigrants of maintaining their native language, probably because it is of little interest in the context of a country where one language clearly dominates. The few studies that have looked at this issue have generally found that for members of some minority groups, the use of the native language by migrants brings low or even negative returns [10]. To some extent, this finding reflects the fact that immigrants who continue to use their native language predominantly do not fully integrate into the economy and society of their new country of residence. Many migrants work in ethnic enclaves, mainly with workers who also speak their native language. The enclave economy has some advantages, in that it links immigrants to networks of fellow immigrants, but wages are generally much lower than in the mainstream economy.

Linguistic diversity also has value

The results so far clearly show that learning a dominant language is a good investment in human capital. If the primary motivation for learning a second language is the desire to communicate with more people, there should be a convergence toward a few languages or even just one. It is the case that many languages are disappearing. As of 2020, out of more than 7,000 living languages, about 3,000 are endangered [1]. These figures seem to suggest that linguistic diversity is gradually decreasing. However, looked at another way, linguistic diversity can also be seen as increasing. As a result of globalization, more and more people find themselves in situations where they have to communicate with people who speak a language different from their own. One such situation arises from international migration, especially the rapidly rising migration from developing countries to developed countries.

This need to communicate across different languages makes it important to examine the impacts of linguistic diversity, which can be both negative and positive [9]. In the context of the first of the four hypotheses mentioned above on the economics of language (a population's economic well-being is enhanced when its members can communicate in a single language), the impact of diversity is negative.

In the modern world, where linguistic conflicts can also have some costs, there are some countries, such as Belgium and Canada, that might be better off if they did not have to live with the frictions caused by having two different linguistic communities. However, the costs are probably low since the standard of living in those countries is not much different from that in more linguistically homogeneous neighboring countries. Democratic institutions can help to reduce such frictions. But in poorer, less democratic countries there is evidence that language fragmentation can be detrimental to economic development [9].

There is some evidence that the costs of linguistic diversity are relatively small, though they are difficult to estimate. For example, providing bilingual education may raise the cost of education by 4–5% compared with the cost of monolingual education, largely because additional teaching materials and teacher training are needed [3]. However, this seems to be a burden that many people are willing to accept in order to transmit their language to the next generation.

Linguistic diversity also has benefits. These may be more difficult to measure because they are not necessarily monetary. Because of the strong link between culture and language and people's preference for using their native language, the more languages that can be accommodated in a given society, the greater the welfare of the members of that society. In addition, people can benefit from contact with cultures different to their own. Linguistic and cultural diversity can increase the number and type of goods that are available in a society. For example, ethnic restaurants contribute to the vitality of cities.

A study over two decades of 160 metropolitan areas in the US provides some quantitative evidence of the monetary benefits of linguistic diversity [11]. The study considers the average wage in those cities as a function of such characteristics as education, age structure, racial composition, location, and industrial composition, plus an indicator of the linguistic diversity of the population. Although there used to be a belief that linguistic diversity might increase communication costs and thereby reduce productivity, the study finds a strong positive link between linguistic diversity and average wages. However, it is true that economists have not yet reached a consensus on whether the effect of linguistic diversity on the labor market (and the rest of the economy) is positive or negative.

Commenting on the debate on bilingual education in the US, and in reaction to the English-only movement there, one study has collected the findings of various studies of the effect of bilingual education and linguistic diversity [10]. The major message is that there are advantages to bilingualism in the US but that they are not easy to identify or measure. For example, given the large size of the Spanish-speaking community in the US, many employers report that they value workers who know Spanish in addition to English. However, these bilingual workers are not necessarily paid any more than workers whose only language is English. These employers may require their workers to know the dominant language while still viewing workers’ knowledge of a second language as an asset whose value may differ for different companies and in different contexts.

The situation is different in Europe, where many languages co-exist, though individual languages are concentrated in a particular territory. Many people learn a second or third language in addition to the dominant language in their country, usually the language of neighboring countries. In Europe, as in the rest of the world, English has become the preferred second language, especially for the younger generation [12]. Nevertheless, knowing other languages that enjoy a high enough status brings significant benefits in the labor market [9].

The case in China is mixed, somewhere between the US and Europe. On the one hand, Mandarin works as the sole and mandatory official language, and people can obtain large monetary benefits by speaking it. Speaking Mandarin is also conducive to migrants’ social integration. This is very similar to the evidence of learning English as a lingua franca in other countries. On the other hand, despite that Mandarin is the official language and is spoken by the majority of the population, more than 300 languages co-exist in China [1], which indicates a large amount of linguistic diversity. Under such circumstances, speaking languages other than Mandarin (e.g. local languages of communities or regions) can also bring benefits, especially in the southern part of China and some coastal areas. However, those benefits are relatively hard to measure compared to those of speaking Mandarin.

Support for the rights of linguistic minorities is often expressed by the intellectual and political elites of those groups. For instance, people whose work has a large linguistic component (such as novelists and singers) may have preferences for a non-dominant language that is not necessarily shared by all speakers of that language. Even if the extent to which the support of the intellectual and political elites reflects the views of the broader population is questioned, it is nonetheless the case that as elected officials, the political elites must represent, at least to some extent, the will of the population. Therefore, public support for maintaining a minority language can be considered an indication that people value their native language and are willing to take actions to maintain it.

Limitations and gaps

The non-pecuniary benefits of linguistic diversity (such as the feeling of belonging to a certain group) remain difficult to estimate directly, despite indirect evidence of their existence. Clearly, the fact that the labor market rewards monetarily those who use the dominant language should not be interpreted to mean that everybody should speak the same language. And while there is some evidence that the costs of linguistic diversity are relatively small, the costs are difficult to evaluate, and few studies have tried to do so.

Very little is known about how context affects which language people are willing to use. Because of the symbolic role of language as a carrier of culture, specific contexts may determine how much people are willing to compromise in their use of their native language. For example, some people may insist on the right to use their native language in interactions with the government, while accepting the use of the dominant language of the country or of the world in their business transactions. Including survey questions on which languages people consider acceptable in various situations would make it possible to study this issue.

Summary and policy advice

Language has economic value, both as a tool of communication and as a cultural manifestation. Its value as a cultural manifestation has not generally been expressed quantitatively, but it is nevertheless important. Because the economic benefits of a common language go beyond personal benefits to wider social benefits (externalities), including making the economy more efficient, governments may encourage or impose the use of a language that some members of a community would not choose to use on their own. Policies may vary according to the specific circumstances. Some countries have a single dominant language that co-exists with one or more other languages spoken by linguistic minority groups, either of long-standing or recent migrants. Other countries have tolerated multiple important language groups for a long time. The official status of the various languages can also vary, from equality of rights to the exclusion of some languages, with different kinds of accommodation possible in between.

While there has been a tendency toward language convergence globally, there is also a desire to maintain diversity. Although seemingly at odds, the two objectives can be pursued together in countries where a large number of people are bilingual or multilingual. Bilingual and multilingual countries, like Belgium, Canada, and India, have frequently experienced tensions arising from the relationships among their main language groups. Those tensions can be attenuated in various ways, including by territorial separation that recognizes different languages as dominant in different parts of the country. Arrangements can be made to address the problem of communication across regions; these often involve the official recognition of several languages in some domains of activity.

Monolingual countries may have an advantage, but they may also experience some of the problems of multilingualism if they have large linguistic minority groups. In the US, for example, more than one in five people speak a language other than English at home. Even in China where Mandarin dominates, a large proportion of people are not able to understand or speak Mandarin. The penetration rate of Mandarin for the whole country is 81%, and it is less than 65% in some remote rural areas and minority regions. Clearly, some accommodation is necessary.

Immigrant-receiving countries, while showing consideration for the cultures of newcomers, must also ensure that they adapt to their new environment. As research has shown, knowledge of the dominant language is crucial for immigrants’ integration into their new country. This importance is acknowledged by a common criterion for the selection of immigrants: some knowledge of the main language of the receiving country.

International organizations such as the EU also struggle with their language practices. There are now 24 official languages in the EU. This accommodation of multiple languages can be costly and requires a large bureaucracy to administer. Despite the willingness to accommodate many languages, English is increasingly used in European institutions as a main language of communication, which creates some frustration. And not all languages that are spoken in Europe are officially recognized, leading some to complain that people who speak non-recognized languages are being disenfranchised [9] and suffer a loss of welfare.

With globalization, more languages are becoming endangered and some are being lost. English has become the preferred second language as an international lingua franca. While a common international language has some advantages in making communication easier across borders, globalization also leads to wealthier societies, with more educated people who are interested in other cultures. This growing interest in other cultures and languages could, to some extent, counterbalance the trend toward the use of a single language. Education systems around the world could promote the learning of foreign languages and cultures.

A recent analysis of language policy from a fairness perspective takes the provocative position that “the spreading of competence in English should not be resisted or reversed, but on the contrary welcomed and accelerated” for reasons not only of efficiency but also of fairness [12], p. 50. The use of a common language is fair in the sense that it enables access to knowledge for the largest number of people. While many observers of the world linguistic situation might object to the idea that the common use of English should be accelerated, there is probably more agreement that the trend cannot be changed in the foreseeable future. However, the use of a lingua franca does not mean that all other languages have to disappear. A common language can be combined with a system of territorial language rights in a mutually supportive system. In a given country or territory, a local language may be allowed to dominate while the lingua franca is encouraged as a second language for communication with the rest of the world. Not every language would survive in that kind of system, but it would guarantee the persistence of a large number of them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the authors contains a large number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [4], [6], [7]. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of D. E. Bloom and F. Vaillancourt to that work. Version 2 of the article updates the figures, adds a section on Mandarin language use in China, and updates the references, including adding new “Key references” [1], [5].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Gilles Grenier and Weiguo Zhang