Elevator pitch

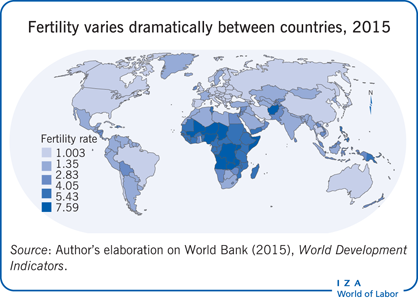

Demographic factors in migrant-sending countries can influence international migration flows. But when migrants move across borders, they can also influence the pace of demographic transition in their countries of origin. This is because migrants, who predominantly move on a temporary basis, encounter new fertility norms in their host countries and then bring them back home. These new fertility norms can be higher or lower than those in their country of origin. So the new fertility norms that result from migration flows can either accelerate or slow down a demographic transition in migrant-sending countries.

Key findings

Pros

The movement of migrants across political borders can influence fertility in the country of origin.

International migration can influence fertility in either direction, depending on whether it is higher or lower in the host country than in the country of origin.

Returning migrants can bring home the fertility norms they encountered while abroad.

Migrant couples often have more children than non-migrant couples, e.g. Egyptian couples with a past migration experience in other Arab countries have a higher number of children than non-migrant couples do.

Cons

It is difficult to separate the effects of the transfer of norms from the other effects of a past migration experience, such as improvements in households’ economic conditions.

The decision to migrate (and return) might be correlated with individual fertility preferences.

Egypt is the only country for which evidence from household-level data on the transfer of fertility norms controls for non-random selection into migration.

The possible multiplier effects on non-migrants who encounter returnees have not yet been explored.