Elevator pitch

Private charitable contributions play an essential role in most economies. From a policy perspective, there is concern that comprehensive government spending might crowd out private charitable donations. If perfect crowding out occurs, then every dollar spent by the government will lead to a one-for-one decrease in private spending, leaving the total level of welfare unaltered. Understanding the magnitude and the causes of crowding out is crucial from a policy perspective, as crowding out represents a hidden cost to public spending and can thus have significant consequences for government policies toward public welfare provision.

Key findings

Pros

If people are only concerned with the total level of welfare provided, they will treat government spending as a perfect substitute for their own donations.

Crowding-out behavior is observed in laboratory experiments, which show that tax-financed contributions largely crowd out individuals’ charitable contributions.

Even if crowding out is small, potential negative consequences of a reduction in private philanthropy must be considered.

Cons

The decision to contribute privately is determined by many other factors beyond the total level of welfare, such as the individual’s desire for earning respect or social prestige, the utility derived from the act of giving itself, or the expected success of giving.

Apart from the laboratory setting, there is hardly any empirical evidence to suggest that government spending largely crowds out individual charitable behavior.

Studies based on micro-level data from charities or donors as well as studies using regional or cross-country variation in private and public spending usually find small or incomplete crowding-out effects, or even some evidence of a crowding-in effect.

Author's main message

The empirical evidence investigating whether public spending crowds out private charitable donations is mixed. A number of studies find significant but small crowding-out effects, while others find no effects or even evidence of a crowding-in effect. Hence, while crowding out might exist, it is far from being perfect. Policymakers should therefore acknowledge that their own expenditure on social welfare influences private spending. However, they should not be too concerned that an increase in government spending will largely crowd out private contributions of time and money.

Motivation

Private contributions of time and money play an essential role in most economies. Despite the existence of welfare states, people contribute money or volunteer labor for charities. However, little is known about why people decide to devote their time and money to charity. Closely linked to questions about the motives for prosocial behavior is the role of the welfare state in determining the level of private charitable contributions. If people are only concerned with the total amount of welfare provided, they should treat government spending as a substitute for their own donations. In such a situation, an increase (a decrease) in government spending would result in a one-for-one decrease (increase) in private spending. This is referred to as “perfect crowding out,” and it has important policy implications. On the one hand, policymakers should be concerned that an increase in welfare spending will significantly lower the engagement of nonprofit organizations and private donors. On the other hand, it implies that the private sector will assume more of the responsibility for the provision of social services when the government decreases its level of welfare provision. If this holds true, public spending cuts could be justified based on the idea that the private sector takes over [1].

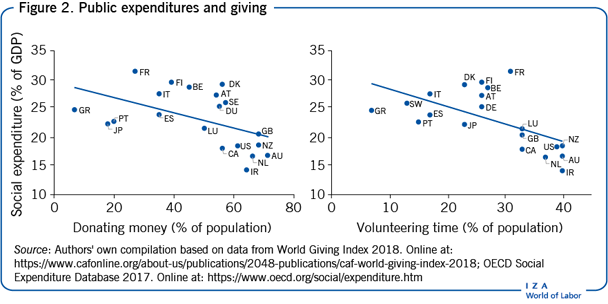

To prove the existence of a crowding-out effect, a comparison is often made between the US and Europe. The US, which is characterized by a low level of public welfare provision, is traditionally known for being one of the countries with the highest levels of charitable giving and volunteering worldwide. Europe, in contrast, is characterized by an extensive welfare state and a considerably lower private provision of charitable activities. Consequently, it is possible to jump to the conclusion that extensive welfare states crowd out private charitable behavior. Whether this conclusion is justified, however, is a matter of debate.

Discussion of pros and cons

Determinants and cross-country variation of voluntary labor and donations

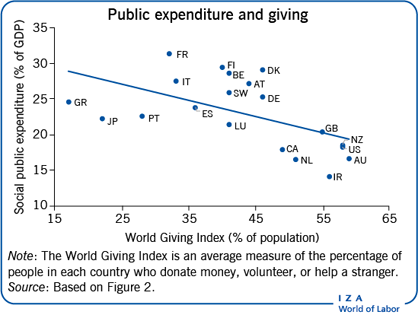

There is not only a large difference in the role of charitable activities between the US and Europe, but also a high variation across individual countries. This is shown by the World Giving Index, a yearly survey conducted in 135 countries, which measures three different aspects of giving behavior: the percentage of people who in a typical month (i) donate money to charity, (ii) volunteer time to an organization, or (iii) help a stranger. Based on information provided in the World Giving Index 2018, Figure 1 shows the percentage of individuals that donated money and volunteered time to a charity for a selected set of countries.

Figure 1 illustrates that countries with a high share of voluntary workers also tend to exhibit a relatively high share of charitable giving, suggesting a positive correlation between monetary and time donations (the correlation coefficient is 0.74, where 1 indicates perfect correlation). All countries, except for France, Japan, and Greece, show a higher proportion of individuals who donate money than who volunteer labor. Most important, however, is the large variation in charitable activities across countries. In particular, the Anglo-Saxon countries (Australia, the UK, New Zealand, Ireland, the US, and Canada) show the highest degree of charitable activity. Within the European countries, the northern European countries rank highest, while the southern European countries rank lowest.

Cross-country differences in voluntary donations could be partially explained by differences in the composition of the countries’ populations [2]. And indeed, individual characteristics do play an important role in the decision to contribute to charity. Focusing on Europe, a study investigates the determinants of the individual decision to donate time or money using data from the 2002/2003 wave of the European Social Survey, which contains detailed information on individuals’ voluntary activities in charitable organizations [2]. The study corroborates the assumption that volunteering is a normal good (i.e. if income rises, the demand for the good also increases) and finds a positive correlation between an individual's income and that person's probability of donating time and money to charity. It further shows that highly educated and older people are most likely to engage in charitable activities, while women and immigrants are less likely to donate time to charitable organizations. Moreover, religious people, as proxied by church membership, are more likely to donate time and money to charity. The authors also find differences in the individual determinants of charitable behavior across European countries, in terms of educational attainment, gender, and immigration status. However, these individual differences alone are not sufficient in explaining the large variation in charitable activity across countries.

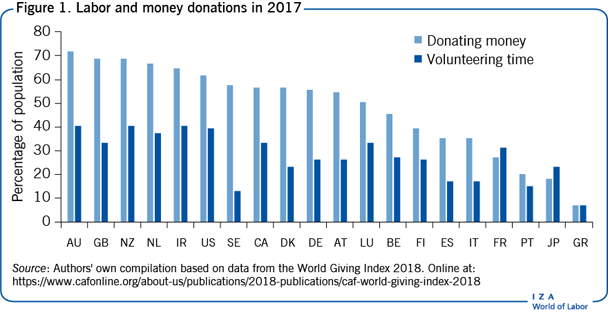

Another explanation for the cross-country variations in charitable activities could be that individuals in different countries face different environments and thus incentives to contribute privately. In particular, people living in countries with an extensive welfare state financed by taxes may feel that the state already provides the needed services, so contribute less. Figure 2 supports this hypothesis, showing a simple correlation between the share of individuals contributing time and money to charity and government spending. For both money and time donations, there is a negative correlation between private and public contributions, suggesting that individuals treat government spending as a substitute for their own donations. However, while such a descriptive analysis suggests the existence of a crowding-out effect, both theory and empirical evidence on the crowding-out effect are rather inconclusive.

Theoretical background: Crowding-out effect

To determine whether government spending crowds out private philanthropy, it is important to understand what drives individuals to contribute time or money to charity. In economic models, prosocial behavior is often regarded as “altruism,” which implies that there is no immediate gain for the contributing individuals. This raises the question of what motivates donors to give: the desire to increase the supply of a certain public good or the utility gain from the act of giving itself?

The traditional public good model of charitable giving suggests that individuals contribute to welfare provision because they are concerned with the utility of the recipients [3]. Donors are assumed to be “purely altruistic,” meaning they are only concerned with the total level of welfare, irrespective of the source of funding. Thus, they consider their contributions to be a perfect substitute for other private or public contributions. The model suggests that if the government provision of welfare increases, this would lead to a “dollar-for-dollar” or “one-for-one” adjustment in the donors’ giving behavior, and the opposite is true for a decrease in public welfare provision. Therefore, if a public good is financed through private donations, a subsequent increase in government spending on the same public good would perfectly crowd out private donations.

So far, this theoretical model considers only monetary donations. However, the public good model can be extended, also taking into account time spent on charitable activities [4]. The extended model suggests that individuals view their contributions of both money and time as perfect substitutes. In this framework, government spending will not only crowd out monetary donations, but also the supply of volunteer labor. As a result, empirical studies that ignore time contributions are incomplete, as they underestimate the true crowding-out effect.

Private charity donations, however, might not only be determined by altruism, but also by other personal characteristics like the individual's desire for earning respect, social prestige, or a “warm glow” feeling, which represent the individual's utility derived from the act of giving itself [5]. This motivation is called “impure altruism”; it implies that private donations have an altruistic component, which is the donor's concern about the total level of welfare, as well as an egoistic one, which is the personal utility gained from the act of donating. This is equivalent to assuming that contributions to charity are not a public good, but rather a private good. In this case, an increase in the government provision of a public good is not automatically followed by a one-for-one decrease in private contributions.

An additional motive for altruism to be less than perfect is the individual desire to seek status or demonstrate wealth. According to this argument, individuals give not only to increase the provision of public goods, but also to signal their income level or high status. Another possibility is that larger government spending crowds in private donations because donors are not completely informed about the quality of a given charity. This is referred to as a signaling effect, where a large amount of government contributions acts as a signal of the charity's need and quality, which results in attracting additional private donors. In this case, increased government spending increases private contributions due to the positive signal given by the public sector. The signaling effect can also be extended to giving in general. This argument goes along with welfare regime theory, which suggests that public spending may have an influence on the donor's sense of obligation. A larger government contribution might induce people to donate privately because of a more persistent collective social concern [6].

While the “warm-glow” implies a preference for prosocial behavior, negative feelings could also motivate giving [7]. If certain individuals dislike giving, they may anyway feel forced to donate to avoid negative feelings associated with selfishness, such as shame. For these individuals, rewards or fines to encourage prosocial behavior may in fact lead to more selfish behavior, as freedom is important to the choice of giving. Current literature is further investigating the role of “reward” interventions to encourage charity donations such as tax rebates or matched contributions. A recent study suggests that under impure altruism it is not clear a priori how such interventions could impact charitable giving. The theory predicts different responses to match and rebate incentives [8]. Rebates lead to a conventional price effect because they decrease the price of giving. However, matches combine two opposing price effects: a weaker substitution effect due to the warm glow and a stronger income effect due to the match. Depending on which effect prevails, impure altruism could decrease the effectiveness of matched contributions.

Empirical evidence: Crowding-out effect

The theoretically predicted crowding-out effect is investigated in a number of empirical studies. This literature can be classified into three main strands: (i) studies using micro data at the charity or donor level, (ii) studies using cross-country or regional variation to identify the crowding-out effect, and (iii) experimental studies [1].

Evidence based on charity or donor data

Studies based on charity data are able to analyze different sources of revenue for each organization. In general, charity data provide information on the revenue generated from three main sources: autonomous income, private contributions, and government grants. Empirical studies using this type of data typically show a small degree of crowding out, or even a modest crowding in. In spite of the advantages of using charity data, some econometric issues need to be taken into account. Especially, the amount of public grants received by charities may be determined by unobserved factors that cannot be accounted for. For example, the charity's reputation could be correlated with both public and private contributions and not taking this into consideration would lead to biased estimates.

A common way to address the endogeneity problem is, for example, to implement an instrumental variable approach. However, finding an instrument that fulfills all necessary assumptions, that is, being highly correlated with government spending, but uncorrelated with private charity giving—except through government spending—is challenging. The few studies for the UK and the US using this methodology tend to find evidence of small crowding-out effects. Studies that find larger crowding-out effects using this approach suggest that the effect is entirely driven by a decrease in fundraising activities.

Recent studies address the endogeneity problem using quasi-experimental settings. For example, a study for the UK uses data on 5,000 charities that applied for a grant to the National Lottery between 2002 and 2005 [9]. The authors compare the change in charity income for successful and unsuccessful applicants before and after the grant. Although the grant is not allocated randomly, the authors show that it is uncorrelated with pre-existing trends in charities’ incomes. The study finds that grants do not crowd out other funding sources. In fact, for medium-sized charities, the authors find small crowding-in effects.

A study for the US focuses on lottery revenue at the state level from 1989 to 2009 [10]. This revenue contributes to the state's yearly budget and is typically used to provide additional support for public goods, in particular education. The study assesses the degree to which lottery revenue to fund education has an impact on donations using individual-level survey data. In particular, the study compares changes in individual education-related donations in states with and without a lottery revenue to fund education programs. The study finds that lottery revenue decreases private contributions by 8%, suggesting a small crowding-out effect. This crowding-out effect can be partially explained by more prevalent advertising of lottery revenue to fund education programs in some states.

Finally, a recent study investigates how tax incentives impact charitable giving focusing on the 1986 Tax Reform Act in the US [11]. The findings suggest that a 1% increase in the tax cost of giving leads to a 4% decrease in donation revenues. Although the focus of this study is on tax incentives, it provides valuable contributions on potential sources of heterogeneity based on charities’ characteristics. In particular, if donors perceive that a charity is well-funded by other sources of revenue, they will see their giving as dispensable, and thus decrease more strongly their contributions after a tax increase. This implies that the crowding-out effect largely depends on the charities’ financial structure.

Studies using regional or cross-country variation in public and private spending

Several studies have analyzed the effect of the extent of the welfare state on charitable activity using regional or cross-country variation in public spending and private philanthropy. Although the crowding-out theory would suggest that a higher level of public spending induces people to volunteer less, these studies find very little empirical support for this assumption.

Analyses of the crowding-out effect based on cross-country comparisons use either individual survey data on volunteering collected across different countries or aggregate data on the share of the population participating in charitable activities. These data are then correlated with measures of public welfare, such as public social expenditure. Analyses focus on voluntary labor supply and usually find hardly any evidence for a crowding-out effect; in some cases, they even present evidence for a crowding-in effect. However, these results might be biased because of the existence of time-invariant unobserved factors at the country level that are correlated with both social expenditure and volunteering rates, such as cultural or religious differences, or differences in wealth.

One exception is a study that combines individual data from the World Values Survey with macroeconomic data from the OECD [12]. The data cover 24 OECD countries for 1981–2000 and contain information on individual participation in voluntary work as well as on countries’ public social expenditure as a percentage of GDP. In contrast to previous analyses, this study uses the panel structure of the data to address the problem of time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity at the country level, which might be correlated with both public and private contributions. The results show that an increase in public social expenditure significantly decreases the probability of volunteering, which suggests that government support lowers individuals’ incentives to participate in volunteering activities.

In contrast, a study examining the relationship between government expenditures and individual private giving using a cross-country database of 19 countries finds the opposite result [13]. The study finds heterogeneous crowding-in effects which depend on the field and the main funding source. For instance, the authors find a positive relationship between government spending and philanthropic donations. This relationship is stronger for certain fields such as education, research, and environment. In addition, the findings reveal evidence of crosswise crowding-in effects, that is, higher public expenditures in core welfare fields tend to drive donors to increase their donations in other fields.

Studies using aggregate data on public and private spending at a regional level, such as the state or province, also find hardly any evidence of a crowding-out effect. A study published in 2015, for example, employs historical data from the UK during the 19th century [1]. The study uses data on a universal welfare spending program implemented to help the poor, and the income of private charities at the county level. Applying a simple regression technique, a pooled Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model, the study finds a positive correlation between poor relief spending and charity giving. However, as this result might be driven by reverse causality, that is, by a potential effect of private spending on public welfare provision, the authors further apply a difference-in-differences and an instrumental variable approach to identify a causal relationship between public and private giving. They use the distance from the county to London as an instrument to predict poor relief. The idea is that distance from London is exogenous, but that counties located closer to London provided a higher level of poor relief to keep laborers in their parish and avoid migration. While the instrument has the downside of lacking variation over time, the authors conduct several robustness checks to rule out that unobserved confounding factors at the county level still bias their results. The results of the instrumental variable approach are similar to those of the OLS model.

Evidence based on laboratory experiments

While the studies described above represent an indirect test of the motives underlying charitable behavior, experiments provide a way to more directly elicit information on individual preferences and motivations. Most economic laboratory experiments that test the crowding-out hypothesis implement extensions of the so-called “dictator game.” The dictator game is frequently used in behavioral economics when researchers are interested in the motivations that lead individuals to redistribute part of their income to others. The idea of the game is simple—each participant (dictator) is given a sum of money and has to decide how to distribute the money between them and another recipient.

One of the first laboratory experiments to test the crowding-out hypothesis implemented a version of the dictator game in order to distinguish between pure and impure altruism [6]. The participants, who were mainly university students, were randomly separated into two groups: donors (group A) and recipients (group B). Each subject from group A was anonymously paired with one subject from group B. The participants playing role A were then asked to decide how they would like to distribute an initial allocation of money between themselves and the recipients, with the possibility of transferring 0–100% of their original endowment. The final payoff for B would then be their respective initial endowment plus the contributions made by A. Two different treatments were implemented in order to test whether the initial distribution of money had an influence on individual contributions. In the first treatment, the dictator was given an initial endowment of $15, while the recipient was given $5. In the second treatment, the allocations were different, $18 was given to the dictator and $2 to the recipient. Perfect crowding out predicts that participants who are willing to give $3 or more in the $18-$2 treatment give $3 less in the $15-$5 treatment, because only the final allocation matters. The results show that, conditional on giving, those with the lower initial endowment ($15-$5) do give slightly less than those with the higher one ($18-$2). This rejects the perfect crowding-out hypothesis, and points toward an extensive but incomplete crowding-out effect.

One of the main downsides of the dictator study described in [6] is that the observed crowding out might not be accurately measured because contributions were given to a fellow student rather than to a person in need. This problem of unrealistic recipient characteristics could be addressed by asking the subjects to allocate money between themselves and a charity of their choice. The studies using this setup reveal a high sensitivity to the experiment framing. For example, when the source of funding is not made apparent to the participants, the crowding-out effect is small. However, when the participants are told that the third-party support for the charity is financed through an explicit tax on their own endowment, private donations are perfectly crowded out.

Another laboratory experiment, which was designed to identify the magnitude of the “warm-glow” effect (i.e. experiencing positive personal feelings as a result of charitable giving), was implemented using a modified version of the dictator game [14]. The experiment was designed in a way such that a pure altruist would not have any incentive to participate. The subjects were given $10, which they could distribute between themselves and a charity of their choice. The chosen charity would also receive money by an anonymous proctor. Any contribution made by the participants would substitute the contributions by the proctor, so that the amount of money the charity received would not be altered by the individual's contributions. The results show that, on average, participants gave about 20% of their original endowment to the charity, suggesting that there is indeed an egoistic motivation behind giving and that people benefit from the act of giving itself.

A recent study argues that the crowding out level depends on the charities’ output level due to impure altruism [15]. In this experimental design, the participants received $40, which they could distribute between themselves and a child whose house had suffered extensive fire damage. The participants were also informed that a foundation would donate a fixed amount of money, and that the money would be used jointly to buy books for the child. The participants were told different amounts the foundation would donate ranging from $4 to $48 (low and high charity output levels) and asked to voluntarily top up this amount using their initial endowment. The results show that at low levels of charity output, if the charity increases donations, these donations will completely crowd out private donations. However, the crowding out decreases as the charity output increases, consistent with impure altruism.

Finally, recent studies have also shown that individuals derive utility from “the success of giving” and not necessarily from the act of giving itself. In experimental settings, a risk variable can be introduced that measures the “success of giving to others” for the player themself and for other players. The findings suggest that decreasing the risk of giving is an effective way of stabilizing donations even when other sources of funding are available.

Limitations and gaps

While there exists a large literature analyzing whether government spending crowds out voluntary labor and donations, the empirical literature is not conclusive. This might be because the literature is missing a unified framework to test the crowding-out hypothesis. To date, studies have used a range of different approaches; as such, the results are hardly comparable.

The empirical literature generally uses information from charities, donors, or data from across countries or regions to analyze the relationship between private and public welfare spending. These studies often suffer from an omitted variable bias, that is, the potential influence of unobserved factors at the charity or the country/regional level that are correlated with both public spending and private charitable contributions. While this issue is partly addressed by employing panel data or by exploiting some sort of exogenous variation in public spending in an instrumental variable approach, the literature would clearly benefit from more convincing identification strategies, such as natural experiments.

Laboratory experiments overcome these empirical problems and thus represent a useful tool to test the effect of public spending on private spending, thereby providing helpful insights into the individual motivations behind private giving. However, due to the artificial settings, the extent to which the observed behavior can be generalized to the world outside the laboratory will always remain unclear. The few studies relying on quasi-experimental evidence exploit charity grant applications or changes in public funding structures. These studies find small crowding-out effects or even evidence of crowding in. However, the limitation of these studies is the external validity of the findings as the studies focus on a specific type of charity or public funding.

Besides differences in underlying data and empirical approaches, studies vary with respect to the charitable behavior considered. While most studies focus solely on monetary donations, cross-country comparisons focus solely on time donations, and only a few studies consider both. If money and time are substitutes (or complements), ignoring one or the other would lead to an underestimation (or overestimation) of the true crowding-out effect. Also, there is no clear definition of the type of charitable good considered. Some studies focus on giving to specific charities, such as health or social welfare organizations, while others consider charitable giving as a whole. In this context, it is also important to note that not all studies are able to perfectly match the reason for making private contributions with the definition of public expenditures. In other words, the purpose for both private and public contributions should be the same, for example, public expenditures on poor relief should be matched with private donations to the same area. Instead, some studies use aggregate values for either public or private spending, thus violating the assumption that the two types of funding are perfect substitutes.

Summary and policy advice

Although there exists a large literature investigating the role of government spending in determining private donations of time and money, the empirical evidence on the crowding-out effect is still mixed. Studies based on micro data on charities as well as cross-country studies usually find small crowding-out effects, while some even find evidence of a crowding-in effect. Laboratory experiments, in contrast, usually find evidence of large, though incomplete, crowding out. The conclusion that can be drawn from the literature is that crowding out exists, but it is far from being perfect. Importantly, the literature shows that the crowding-out effect is heterogeneous with respect to the field of investment, the charities’ revenues, and the expected success of giving.

In conclusion, policymakers should acknowledge that public spending influences private spending. However, neither should they be too concerned that an increase in government spending largely crowds out private contributions, nor can they count on the fact that a decrease in government spending is automatically compensated for by private giving.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts as well as Rachel Kühn for helpful research assistance. Financial support by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Version 2 of the article updates the figures and adds new “Key references” [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [15].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Julia Bredtmann and Fernanda Martínez Flores