Elevator pitch

Many countries around the world are making substantial and increasing public investments in children by providing resources for schooling from early years through to adolescence. Recent research has looked at how parents respond to children’s schooling opportunities, highlighting that public inputs can alternatively encourage or crowd out parental inputs. Most evidence finds that parents reduce their own efforts as schooling improves, dampening the efficiency of government expenditure. Policymakers may thus want to focus government provision on schooling inputs that are less easily substituted.

Key findings

Pros

Parents may respond to changes in public school inputs by adjusting the time and money dedicated to their children’s education, potentially affecting the impacts of public policies on students’ learning.

Parents often reduce their own efforts as schooling improves, suggesting that public and private investments in children are substitutes.

Crowding out of parental inputs is more likely for school inputs that are easily substitutable and observable.

Limited evidence suggests that more-educated parents respond more to changes in school quality than less-educated parents.

Cons

The literature is not in agreement, with some studies presenting contradictory results.

Evidence often focuses on a limited set of inputs from schools and parents, while adjustments may occur across a multitude of dimensions.

Apart from parents, students and teachers will react to changes in school inputs, about which very little is known.

Not enough is known about how parental responses to school inputs impact test scores.

Author's main message

Parents respond to improvements in schooling, primarily by reducing their own efforts. This indicates that public investments in children might crowd out private investments, thereby dampening the impact of public policies on student outcomes. Based on the evidence to date, which is still in its infancy, policymakers can expect the best results from investing in items that are not easily substituted by parents such as specialized instruction and on children whose parents are less responsive, as well as by strategically managing the release of information on school inputs to parents.

Motivation

Governments around the world are investing a substantial proportion of national resources in educating children in schools. On average, OECD countries spent 3.6% of GDP on primary, secondary, and post-secondary (non-tertiary) education in 2014, with 3.3% coming by means of public expenditure. This equates to about US$9,500 per student for the year across the OECD. However, spending varies hugely by country, ranging from US$3,400 in Turkey to US$21,200 in Switzerland, according to OECD figures.

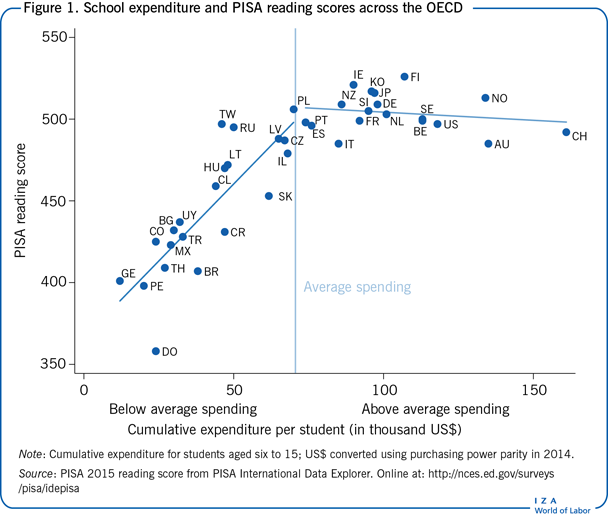

For policymakers, it is important to understand whether increasing school inputs, such as hiring more or better teachers or providing better learning materials, has notable impacts on students’ outcomes. Figure 1 relates the cumulative per student expenditure in OECD countries for pupils aged six to 15 to average reading scores in PISA 2015 (a widely recognized international measure of student achievement). It shows that while higher per-student spending is clearly associated with higher reading performance for countries with a lower-than-average cumulative expenditure (the average being about US$70,600), the highest-spending countries do not achieve notably higher average PISA scores.

In line with the above descriptive evidence, it is a common finding in the education literature based on causal approaches that increasing school spending often has only limited impacts on children's school outcomes (although some specific policies such as reducing class sizes do appear promising). While it is quite possible that there are diminishing payoffs from making more school inputs available to students who are already well resourced, there are other potential explanations.

Recent research has looked at how parents respond to children's schooling opportunities, highlighting that public inputs can encourage or crowd out parental inputs, which can include helping with homework, engaging with the child in other activities, investing money in learning resources, or paying for tutors to help with school subjects. If public inputs encourage parental involvement this would presumably amplify the overall impact on children, while if they crowd out parents’ efforts the impact of public investments would be diminished.

Whether school investments displace parental efforts may depend on the type of input as well as the abilities and constraints of the parents. Knowledge of how parental and school inputs interact will be informative for policymakers deciding which school inputs to prioritize and how best to target them to maximize their impact on school performance. This could in turn strengthen the relationship between spending and test score outcomes.

Discussion of pros and cons

Education production and input interactions

Researchers often compare the development of skills in a child to the production process of a firm. The main aim is to understand how different inputs by schools and parents combine to produce educational outcomes [1]. For example, teachers are considered instrumental for children's learning, but their inputs will be less effective if children do not have access to learning resources and stationery (alternatively computers) in school. In the same way that different inputs in school can rely on each other, inputs by parents and schools may interact to produce children's educational outcomes.

If parental and school inputs are substitutes (i.e. they are interchangeable), then parents may decide to reduce their own efforts when they see school inputs increase, implying that the impact of school investments would be diminished. For example, if parents see that children receive more individual attention because class sizes decrease, they may decide to spend less time helping their children with homework, and vice versa. On the other hand, if parental and school inputs are complements in the production of skills (i.e. one cannot thrive without the other), the impact of school investments would likely be amplified by parents’ responses, who will increase their own investments to ensure their children get the most benefit from school resources.

The total effect of any policy is the sum of the direct impact of that policy, for example spending resources in schools, and the behavioral responses by parents, which may be positive or negative, thereby amplifying or reducing the direct policy effect. Apart from considering parental inputs, this framework can be extended to consider the responses from children themselves, as well as from teachers or schools.

The question of how parental and school inputs interact is also interesting because it can potentially help shed light on why school investments are often found to have different effects for children from high- versus low-income families. Empirical studies typically find that children from low-socio-economic status (SES) families benefit more from education interventions, and this may be because their parents are less likely to adjust their own inputs in response to school investment. For policymakers, this would suggest devoting a higher proportion of resources to disadvantaged children [2].

Empirical findings

For years now, the focus of research on parental responses to school quality has been on so-called extensive margin choices, that is, parents choosing a different school, sometimes alongside a residential move, in the pursuit of improved schooling. This literature has looked at the factors that determine school choices, often in the context of school accountability policies, which involve publishing information about school quality. A part of this literature has looked at how school quality is capitalized into house prices, with significant house price premia documented for residential areas that offer access to good schools.

In contrast, to date there are only a relatively small number of empirical studies on input interactions related to the production of educational outcomes. These studies look at so-called intensive margin responses to school quality, where parents adjust their own inputs without switching schools. The main reason that this area of research is relatively under-developed is because data that comprehensively measure both school and parental inputs are hard to come by. Moreover, to establish a causal relationship, researchers usually look at the outcomes of experiments or “quasi-experiments,” in which school inputs vary for reasons that are unrelated to the unobserved characteristics of families. This is important because very motivated parents may choose high-input schools and help their children a lot with homework, but in this case it is the motivation that is driving both, rather than the level of school inputs affecting parental inputs. However, situations where school inputs vary randomly do not occur often in practice.

Several studies have used maximum class size rules, where classes are split in two once student numbers exceed a certain maximum, leading to variation in the number of pupils taught by one teacher that are unrelated to students’ characteristics. Other approaches have included using test score thresholds that channel children with very similar scores into higher- and lower-quality schools, as well as random assignment of resources to schools or of children into a schooling program. Some studies compare siblings within a family to avoid the confounding influence of the family.

Most such studies find that school and parental inputs are substitutes, that is, that parents reduce their own efforts as schooling improves. Evidence from school grants in India and Zambia for learning materials such as stationery and textbooks shows that parents reduce their own spending on educational inputs when they anticipate increases in school spending, but not if these grants come as a surprise [3]. Two studies on the US find that as per-pupil school expenditure goes up, parents reduce their own effort. The first captures parental effort by using measures of how often parents discuss various school issues with their children and engage in activities with the school [4], while the other proxies this by using maternal labor force participation [5]. Evidence from variation in class sizes suggests that higher-income parents in Sweden increase their help with homework as class sizes increase, while all parents are more likely to switch to schools with smaller class sizes in these circumstances [2].

All of these studies look at how parents react to changes in specific inputs from schools. Two further studies take a broader approach to schooling inputs by using school quality measures. The first captures school quality through summarizing school peer ability. It finds that parents whose children just barely made it into a higher-quality school in Romania reduce their help with homework compared to parents of children who just failed to get into the better school [6]. The second study uses ratings from school inspections intended to capture quality, including factors such as leadership, quality of teaching, personal development, and academic outcomes. It finds that parents in England reduce their help with homework when they learn that their children's school is better than anticipated, thereby isolating the role of information on school quality in the analysis [7].

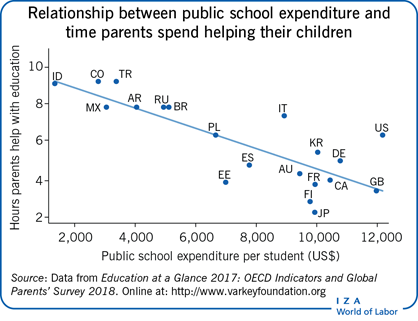

These studies’ results are in line with the descriptive cross-country evidence shown in the Illustration. The figure relates annual per-student expenditure across public primary, secondary, and post-secondary (non-tertiary) schools to the weekly hours parents report helping their children academically. Across those countries for which data are available, there is a pattern of parents investing more time in their children's schooling when fewer financial resources are available for their education in schools.

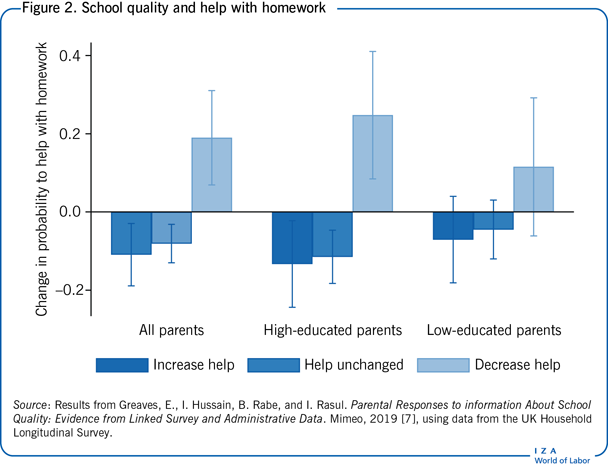

The existing evidence tends to study the population as a whole rather than looking at differences between groups. However, it is intuitive that parents might be differentially able or motivated to adjust their investment behavior in response to variation in school inputs. The study on class size in Sweden shows that while higher-income parents ramp up their help with homework or change schools as class size increases, lower-income parents tend to switch schools, if anything [2]. A similar result comes from the study of school inspections in England. As depicted in Figure 2, parents who receive news that their children's school is better than expected are less likely to increase their help with homework or leave the help unchanged, and are more likely to decrease help than parents who have not yet received such news. Splitting the sample into high- and low-educated parents reveals that this response is driven by high-educated parents, with low-educated parents’ reactions being not statistically different from zero [7].

Conflicting evidence

While the majority of the literature concludes that parental and school inputs are substitutes, there are studies that show the opposite, that is, that parents increase their investments when schools do. For example, evidence based on the US Head Start Impact Study, which ran from 2002 to 2006 and provided preschool for low-income families and was randomly assigned to applicants, shows that parental involvement increased along a number of dimensions such as time spent reading to children [8]. However, specific steps were taken to improve parental involvement through providing information and services directly to parents, so it does not generalize to other policies that do not include such measures. Another example is a study that looks at class size increases in Norway. In contrast to the evidence from Sweden [2], larger classes in Norway led to reductions in parental effort [9]. There are also a few studies that find no reactions from parents to changes in school inputs, at least for some types of inputs (such as parent-school interactions) or parents [2], [10].

One way to reconcile the somewhat conflicting evidence is to look more closely at the types of inputs considered in the research. Not all inputs may be substitutable to the same extent. Pens and stationery are quite straightforward, for example, so that if more pens are provided by schools parents would be expected to buy fewer, as evidenced by the school grant program in India [3]. Other inputs, such as teacher attention (proxied by class size), is perhaps not as easily substituted for at home. Some types of school inputs might naturally inspire parents to do more; for example, if schools improve their feedback and communication with parents, this might enable parents to enhance their own inputs into their children. This suggests that parents’ responses will generally be setting-specific.

Information is also likely to play an important role in determining parents’ responses. School inputs that are not easily observed by parents, such as high-quality classroom teaching, are less likely to provoke a response than those that are more obvious. The study for England using government school quality inspections shows that information release in the context of school accountability systems can provoke significant responses by parents [7]. Likewise, the study comparing anticipated and unanticipated school grants in India and Zambia shows that parents only react to resource changes if they are aware of them [3]. Therefore, responses can change over time as parents learn about changes in school inputs; such responses may only emerge after a policy has been taken to scale and sustained over a longer period of time. Again, the ability to observe subtle changes in resources, such as per-student expenditure, may differ between low- and high-socio-economic status families, as was shown among poor parents in Malawi with respect to knowledge about the academic achievement of children [11].

Test score impacts

Ultimately, the aim of parental and school inputs is to improve children's outcomes, so it is important to understand the extent to which any parental responses counteract the effect of public policy and schooling outcomes. Interesting suggestive evidence in this respect comes from studies that find a parental response from only one of two groups, allowing researchers to compare the achievement of children in the absence and presence of parental adjustments. One such study is that on school grants in India, where parents did not respond to the unanticipated grants in the first year, but did reduce their own spending on learning materials in the second year after they had learned about the grants’ existence [3]. There was a sizeable test score impact of school spending in the first year, which completely disappeared in the second year, indicating that the crowding out of parental investments had wiped out the benefits of public spending. However, it cannot be ruled out that the impact of the grants would have been zero in the second year even if parents had continued to spend as before.

Another relevant study is the one on class size increases in Sweden, which prompted higher-income parents to help their children more with homework, but not lower-income parents, while both types of parents were more likely to change schools [2]. This study, like much of the previous literature, finds that larger classes only negatively affect children of lower-educated parents; it can be inferred that this is because of the differential parental response (although the authors also show that lower-income children find it harder to follow the teacher than higher-income children once class sizes increase, so the effects of the treatment may in fact be mixed). Taken at face value, both studies suggest that parental behavior appears to have sizeable effects on children's outcomes.

Several other studies estimate the overall achievement impacts of public policies including parental responses, but these are usually less informative as to the contribution of parents’ actions because it is not known what the impact would have been in the absence of their help.

Limitations and gaps

While there are a number of lessons to be drawn from the existing evidence, researchers’ understanding of these issues remains somewhat limited. Often, knowledge gaps are linked to the available data. Based on survey data, several studies aggregate responses to questions on parent–child interactions into a measure of parental involvement, but they lack measures of parents’ other inputs such as monetary investments in their children.

Few studies are able to look simultaneously at different dimensions of parental inputs. Those that do tend to indicate that conclusions derived from examining only one input may miss input adjustments along other domains, which could act in the opposite direction. For example, evidence for kindergartens in the US suggests that parents react to increases in group sizes by reducing parent-child interactions, consistent with the evidence from Norway; however, at the same time they tend to increase parent-financed activities such as paid lessons and clubs [10]. A study of randomized high school admissions in Chicago demonstrates that parents of students who win a school-entry lottery and enter higher-quality schools subsequently help less with homework but are more likely to discuss school-related issues [12]. In other words, parents may react to changes to school inputs by substituting one input for another, and if empirical studies are unable to observe all of them, they may draw incomplete conclusions.

Furthermore, it may be important to consider that, apart from parents, other agents may also adjust to changes in schooling quality. For example, individual teachers may begin to exert less effort once more teachers are hired by their school and class sizes decrease, and better teachers may sort into better schools [6]. Likewise, children may also adjust their effort levels in response to changes in inputs by schools, teachers, or parents. For example, a study on Britain finds that by exerting more effort, parents induce their children to also exert more effort, and vice versa [13]. In contrast, the study of school quality inspections in England finds that while parents spend fewer hours directly helping their children with homework when the children's school is of higher quality than expected, children begin increasing the time they spend on homework [7].

Ultimately, apart from the two studies on test score impacts discussed above, there is very little indication of how important parental adjustments to public inputs are for children's schooling outcomes. Knowledge of this is essential to understand whether parents are enhancing or mitigating the connection between policies and their intended outcomes.

Yet another area that requires further investigation concerns the differential adjustments of parents across socio-economic backgrounds. It has become clear that different responses are to be expected based on parents’ ability, access to information, financial means, and preferences; however, despite its relevance for public policy, the existing knowledge base tied to empirical evidence is very limited.

Summary and policy advice

The evidence on interactions between educational inputs from schools and parents suggests that parents often reduce their inputs when they see schools increase theirs, and vice versa. This potentially dampens the effectiveness of investing in public resources. Schools may thus want to think about investing in things that are not easily substituted and that incentivize parents to increase rather than reduce their own inputs. For example, providing stationery in schools may have less impact (due to the crowding-out effect) than offering specialized instruction and learning materials that educate parents about how they can help their children.

It also appears important to carefully design information release to parents, as unanticipated (and by extension hard to observe) inputs are less likely to lead to parental adjustments. However, more evidence is needed on how different types of inputs by parents and schools interact, how this differs between families by economic background, and how students’ and teachers’ own responses affect all of this.

Importantly, while there are indications that parental adjustments may substantially affect children's schooling outcomes, this is not known for certain, and will likely depend on the specific context.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Ellen Greaves and Iftikhar Hussain. Financial support from core funding of the Research Centre on Micro-Social Change at the Institute for Social and Economic Research by the University of Essex and the UK Economic and Social Research Council (award ES L009/53/1) is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Birgitta Rabe