Elevator pitch

Remote work and digital collaborations are prevalent in the business world and many employees use digital communication tools routinely in their jobs. Communication shifts from face-to-face meetings to asynchronous formats using text, audio, or video messages. This shift leads to a reduction of information and signals leaders can send and receive. Do classical leadership and communication techniques such as transformational or charismatic leadership signaling still work in those online settings or do leaders have to rely on transactional leadership techniques such as contingent reward and punishment tools in the remote setting?

Key findings

Pros

Introducing performance pay leads to higher output in online labor markets.

Charismatic leadership communication and signaling can increase worker output considerably in remote settings without leading to monetary costs.

Leaders using rhetorical techniques, an animated tone of voice, facial expressions, and body gestures are perceived as more charismatic in written, audio, or video messages.

The quality of work is not affected by performance pay, punishment mechanisms, or leadership techniques.

Cons

Increasing payment schemes does not induce higher output levels in general.

Unreflected usage of single charismatic rhetorical techniques or references to previous good performance can lead to reduced delivered output.

Non-congruent usage of verbal and non-verbal charismatic signals and communication modes can backfire and lead to lower output.

There is mixed evidence regarding the effect of rhetorical techniques in written communication.

Author's main message

Remote work and digital collaborations are ubiquitous and reduce a leader's available instruments to motivate their followers. This problem is even more prevalent in online labor markets where there is no personal contact. Digital leadership relying on communication such as charismatic rhetorical techniques as well as body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice, can increase follower performance even in anonymous online settings. However, leaders must pay close attention to deliver a congruent appearance; otherwise the communication techniques might backfire, leading to lower output levels.

Motivation

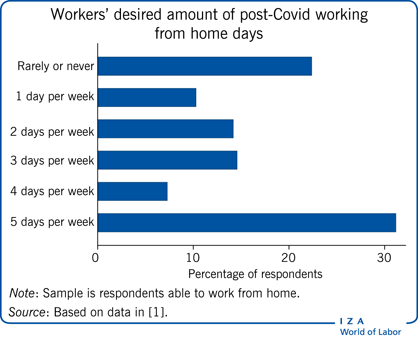

Of all employees able to work from home, 31.2% want to continue to work remotely entirely in the future, whereas 46.4% plan to work remotely for one to four days per week (survey among US residents, see [1]). Remote team collaboration, working from home, and gig work arrangements have become prevalent in many organizations worldwide. This change directly impacts the modes of communication, shifting from face-to-face to online meetings, or even asynchronous forms such as text messages, audio, or video recordings. Leaders, thus, must adapt their management and especially their communication style and engage in so-called digital or virtual leadership [2]. When choosing a communication mode and style, leaders must keep in mind their followers’ expectations, the difficulty of transmitting information, and the standard ways of communicating in their business. They need to find efficient ways to establish trust and cohesion within their teams using online communication.

This overview of current insights and caveats on virtual or digital leadership aims to enable leaders to select effective communication forms besides classical reward and punishment techniques and develop their personal e-leadership style.

Discussion of pros and cons

Digitalization and the low threshold of implementing digital communication tools in many workplaces have pushed traditional face-to-face interactions between leaders and employees into the virtual world. Accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, the share of employees working remotely has increased considerably around the globe. For most people, online communication will remain part of normal work life [1]. In addition, organizations are increasingly using online labor markets and gig work arrangements to complete their internal teams with specialized freelancers [3]. Thus, the traditional work relationship is changing.

Remote work and the gig economy

Both employers and employees can benefit from flexible work arrangements regarding time and place. Many tasks can be done remotely, reducing commuting time and business travel, saving CO₂, and allowing organizations to hire experts around the globe. Employees enjoy more freedom regarding where they want to live if they do not commute to the organization's on-site office every day. Remote work saves time, money, and, possibly, lowers stress levels.

On a more extreme level, organizations might partially dissolve, as new forms of labor such as gig work gain even more importance (see [3] and [4] for details). In the gig economy, individuals offer their skills and knowledge as freelancers to potential employers. Usually, the matching, hiring, contracting, and payment are arranged over platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk), Upwork, or clickworker, which reduces the transaction costs for both parties. The gig economy offers easy access to international experts hired for a specific project. However, those workers are not part of the organization and, thus, do not share the organization's culture and values.

Given that the interactions between employers and workers are often one-time and anonymous, typical strategies to build trust and foster collaboration, such as long-term relationships between leaders and teams, leading-by-example, as well as social norms and shared beliefs, cannot be applied. The offered jobs range from simple tasks to complex programming or design jobs. For instance, on Mturk, gig workers browse the platform looking for suitable jobs. Potential employers publish a short job description, including payment information, and can specify selection parameters such as sex and education as well as the number of previously completed jobs and the approval rate (percentage of previously successfully completed assignments). The complete interaction is online, and the parties never meet in person. Indeed, often the gig workers remain anonymous to the employer, and the communication is purely text-based.

Each employer can evaluate submitted work and either approve and pay the gig workers or reject poor work, leading to no payment and a drop in the approval rate. This mechanism (and similar ones on other platforms) ensures high-quality work and provides general rules for collaboration.

Communication modes, trust, and social closeness

In most organizations, leaders and employees can choose from various communication modes. They can talk face-to-face, or use video calls, audio calls, and chat systems. In all modes, the communication is real-time, with both parties interacting simultaneously. These modes have the advantage that all communication partners can ask clarifying questions and receive an immediate response. On the other hand, synchronous communication requires that all participants agree on a time (and place), which requires coordination effort and makes the communication less flexible. To overcome that problem, leaders and employees use asynchronous forms of communication such as text messages (e.g. emails or instant messaging), audio recordings, or video recordings.

Face-to-face, verbal communication is the richest form of communication, whereas purely text-based communication has more limitations. Typically, followers search for verbal and non-verbal signals that leaders possess specific leadership skills. Besides the content of the message, non-verbal signals and cues play a role [5]. Leaders can intentionally send these signals via their tone of voice, body gestures, and facial expressions. However, leaders also send cues unintentionally, by virtue of, for example, their physical appearance, gender, and age. If leaders use purely text-based forms of communication, they must rely on verbal instruments such as rhetorical elements only [3]. If they use audio communication, they can also use their tone of voice. Leaders can further utilize body gestures and facial expressions when using video to emphasize their message. While video communication comes close to face-to-face meetings regarding the transported information, it lacks the complete set of non-verbal elements present in face-to-face meetings, resulting in less perceived intimacy and social closeness. Typically, a video message only shows the upper part of the body, and hand gestures are limited, as fast movements will lead to blurry video images.

Besides the differences regarding non-verbal signals and cues, communication modes also differ concerning the complexity of information that can be transported. If leaders use video messages, they can visualize complex content, allowing them to address more intricate matters. In contrast, explaining complex issues in a purely written format requires much more effort and is more likely to fail. Thus, using a richer communication mode might be helpful for leaders to establish a more personal relationship, which in turn also results in more trust (see [4] for more details).

Trust and cohesion are considered core elements for teams to perform well and for a productive relationship between leaders and followers. Trust helps to overcome uncertainty regarding the contribution of others and can thus mitigate potential free-rider problems. If there is a regular interaction between leaders and employees, trust and cohesion can grow steadily. However, in remote collaborations and the gig economy, social and physical distances are greater, and the amount of social information about each participant is sparse. Building trust under these circumstances requires more effort from all sides. There is evidence that the level of trust established in online formats depends on the mode of communication and the content of the message. Richer formats such as audio or video communication led to higher trust levels than plain text messages in a recent study [6], indicating that the number of signals plays a role.

Leadership styles in the digital world

For leaders, it is crucial to choose the leadership style that is best suited for a given situation. On the one hand, leaders can use incentive mechanisms such as contingent rewards, which have been studied extensively in economics [7]. On the other hand, leaders could evoke their followers’ emotions and transform their beliefs, for example, about work goals and norms [5].

Contingent rewards and transactional leadership

Leaders regularly use their power to reward and punish followers. For instance, they provide contingent rewards to reinforce high performance. A leader's relationship with their followers is based on a proper exchange of resources. This exchange is often referred to as transactional leadership behavior [8]. Transactional leaders offer bonus payments for good results and punish inferior performance. The provision of contingent rewards and punishment relies on efficient incentive systems and compensation plans in organizations. Contingent rewards work best in simple environments where input or output is easily measurable [7]. However, if, for instance, one aspect such as quality is not easily measurable, the provision of contingent rewards might not be the best option [9]. In most organizations, incentive systems enable leaders to reward good performance. Those incentive systems range from simple piece rates to complex bonus payments. In remote settings, these incentive systems can be used to mitigate the problem of lower social control and potential exploitation. Most platforms already have systems in place in the gig economy where leaders can grant bonus payments for excellent work or refuse to pay for poor results.

One study from 2018 considers the impact of different incentives, including contingent performance pay in a large experiment on Mturk, one of the largest online labor markets [10]. On Mturk, gig workers typically work on simple tasks, such as labeling pictures, transcribing texts, or completing surveys for brief time periods. In the 2018 study, workers had to press the buttons “a” and “b” alternately. Each pair of a-b presses generated one point for the worker. Thus, it was clear to the workers that they participated in an academic experiment and the task had no inherent meaning. The results show that using contingent rewards by offering an output-related piece rate scheme worked. Paying a piece rate led to increased performance. Whereas introducing a low piece rate of 1 cent for 100 points had a strong effect, increasing the piece rate further only led to moderate improvements. The findings align with the results from a 2021 study [3], whose authors also examined worker behavior on Mturk. In contrast to the earlier study [10], they used a transcription task with two dimensions: quality and quantity of the transcribed text. In this setup, introducing a piece rate based purely on output might result in lower quality. In both studies, providing a low piece rate increased output. However, offering a piece rate that was five times higher led to no significant increase of output compared to the low piece rate in the more recent study [3]. Interestingly, the increased output from the low piece rate did not come at the cost of reduced quality. Even if the researchers announced that they would not control for quality and thus the workers did not have to fear that their work would be rejected and not paid, the quality remained stable.

Summing up, techniques based on contingent rewards in the form of performance pay are effective in the gig economy. However, the effect of increasing payments on output is weak and leads to increased costs for the employer. In addition, it is important to keep in mind that paying output-based performance pay is not feasible if the desired output cannot be measured easily [7]. Thus, in more complex remote work environments, contingent rewards might not be the most efficient type of leadership.

Charismatic and transformational leadership

Besides contingent reward and punishment mechanisms, leaders rely on charismatic leadership techniques to motivate their followers and establish trust. Charismatic leadership is defined as “values-based, symbolic, emotion-laden leader signaling” [5], p. 304. The concept builds on so-called verbal and non-verbal leadership tactics or signals that aim to arouse emotions, thereby making the leader's message more salient. Charismatic leaders use, for instance, rhetorical questions or tell anecdotes to provide a frame and create a vision. They announce goals and express moral conviction to emphasize the substance of their message. Non-verbal techniques such as body gestures and facial expressions are often used to signal the leader's emotional state. Note that the charismatic leadership concept is often perceived as part of, or related to, the popular transformational leadership style, which encompasses: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation [8]. Idealized influence and inspirational motivation can be regarded as similar but distinct concepts to charismatic leadership because both are based on communication. Inspirational motivation is triggered when leaders express a vision and set goals. Leaders who show confidence, evoke moral conviction, and share values foster idealized influence. Like charismatic leadership signaling, these two dimensions seem well suited to reach remote workers. In contrast, intellectual stimulation (questioning and challenging followers) and individual consideration (attending to the need for growth) are harder to achieve in a remote setting. However, the concept of transformational leadership has been heavily criticized for its lack of a clear definition and causal evidence [2], [4], [5]. In the following, the focus is thus on studies providing clear, causal evidence based on observed follower behavior.

Charismatic leadership signaling and motivational talk lead to increased performance when used in face-to-face settings and can lead to better results than bonus payments. It has been shown that motivational talk and performance pay can reinforce each other and positively interact [11]. One study exposed temporary workers hired for a one-time job to either a neutral or a charismatic speech containing verbal and non-verbal charismatic signals such as rhetorical elements and body language [12]. The speeches were delivered face-to-face and the charismatic speech significantly increased the temporary workers’ performance compared to the neutral speech. Thus, these techniques work in one-time interactions.

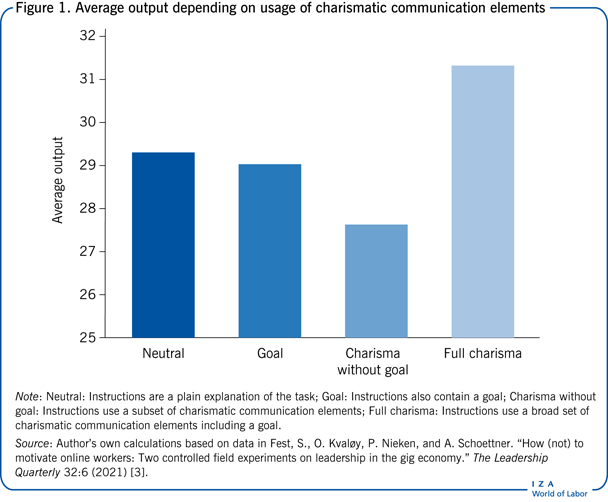

However, the charismatic signals that can be sent in remote collaborations strongly depend on the chosen mode of communication, calling the effectiveness of such signals into question. The previously mentioned 2021 study [3] presents two experiments, both of which were conducted on Mturk. First, the authors investigated the impact of monetary contingent rewards and simple messages on performance, and then studied both instruments’ interaction. Second, they studied charismatic leadership signaling in the gig economy using a purely text-based method. All workers received written instructions about their job. As mentioned above, monetary contingent rewards increased output, but the relationship was not monotonic. In contrast, sending simple motivational messages reduced the delivered output, and there was no interaction between the performance pay and the motivational messages. To explain this backfiring, the researchers conducted the second experiment, where they exposed the workers to four different sets of instructions that build upon each other to implement charismatic signaling. The baseline setup involved neutral instructions containing a plain explanation of the task. The goal setup also included a goal that the workers should reach. In contrast, the full charisma setup contained the goal and a passage that aimed at providing frame, vision, and substance by using rhetorical elements. A fourth setup did not contain the goal part but the charisma part, to allow the researchers to disentangle the effect of goal setting from other charismatic signals. The results show that rhetorical signals indeed impacted the delivered performance (Figure 1). Even for this one-time, ten-minute job without any personal exchange and only text-based one-way communication, using the broad set of charismatic signals significantly increased output. Only announcing goals did not change the output, whereas using only a subset of charismatic signals backfired and even reduced delivered output compared to the neutral baseline. The charismatic signals only influenced the produced quantity but did not affect quality, which was high in all setups.

The above study focused on the impact of pure text-based communication, where non-verbal signals such as body gestures and tone of voice are missing [3]. The instructions built upon each other such that they all differed in length with the full charisma setup providing the longest instructions to the participants. In contrast, a different study from 2021 conducted several studies using video messages [2]. The sample mainly consisted of students hired to participate in an online experiment. The job was to prepare study cards for children in need. It should be noted that this job had a clear mission that might have provided intrinsic motivation in and of itself. In one setup, the students watched a video containing neutral instructions about the job they were expected to do. A trained actress used as many charismatic signals as possible in the other setup. Overall, the authors did not find a systematic impact of the two setups on delivered quality and quantity. The authors also studied the impact of culture by conducting the experiment in a range of different countries (Austria, France, India, and Mexico), but they found no cultural differences.

Another recent study from 2022 focuses on the impact of text-based, audio, and video messages on performance in the gig economy on Mturk [4]. The experiment included a typing task that had inherent meaning. Text fragments were to be digitalized to become part of an extensive collection that scholars and the general public could access. However, the task had no clear moral component, such as the tasks used in [2] and [12]. The gig workers were exposed either to a neutral task instruction or a task instruction using charismatic signals. The instructions were presented as plain text, a video, or an audio recording. In the video or audio recordings, a trained actor also used non-verbal charismatic signals such as facial expressions or intonation where appropriate. This setup allows the impacts of verbal and non-verbal signals in different communication modes to be disentangled. In addition, the data allow the impact of charismatic signaling in each communication mode to be studied. The results show that gig workers indeed perceived the leader to be more charismatic and prototypical if they used charismatic signals. This effect is most vital for video communication. The delivered output was significantly higher in the charisma video setup compared to the neutral video setup. In addition, the comparison of neutral text, versus audio, versus video messages revealed that sending a neutral video message backfired and led to lower output levels. In contrast, there were no significant differences in output when comparing the communication modes under the charisma setup. The delivered quality was not affected by the different setups and was generally high.

Summing up, results from the various studies reveal that the delivered quality of work on Mturk was high no matter which incentive system and which leadership signals were sent. This finding is very encouraging because even in an anonymous online labor market, most regular participants are not shirking. Given that the tasks outsourced to such labor markets are usually those that a machine or artificial intelligence cannot do, this is reassuring. The results differ between the studies concerning the impact of communication signals on the delivered output. However, taken together, it is possible to deduce the following: as a leader, it is essential to deliver a congruent picture. Using rhetorical elements helps to be perceived as charismatic. If non-verbal charismatic signals are absent, this has a strong negative effect. Also, if text-based communication only contains parts of the charismatic signaling instruments, this communication seems to be perceived as non-congruent, and the attempt to motivate followers backfires.

Limitations and gaps

Remote collaborations, the rapid development of new information and communication technology, and their integration into work life are prevalent in today's labor markets. The situation is highly dynamic, and the adoption of new forms of leadership and collaboration is an ongoing process calling for further research and well-developed randomized controlled trials providing clear causal evidence.

The literature on e-leadership providing causal evidence of leadership communication on observed follower behavior is still sparse. The evidence presented in this article is mainly based on data gathered on Mturk. Even though Mturk is one of the largest online labor markets, and controls for demographics help mitigate potential confounds, the rules and regulations of the platform might have led to sorting among potential participants in this particular online labor market. Workers self-select into these gig labor markets and might possess different personality traits and preferences than average employees in organizations. In addition, the samples often consist of workers based in the US. A notable exception is the international study from 2021, which collected data from Austria, France, India, and Mexico [2]. However, the discussed studies use either a student sample or Mturk workers, neither of which have strong ties to an organization and are both groups who self-selected into remote work arrangements. While these studies provide solid insights into the impact of communication in short-term, remote leader-follower exchanges in online labor markets, researchers still lack insights into the efficiency of these communication techniques within organizations where leaders and followers have long-term relationships and occasionally meet face-to-face. In such organizational settings, communication is often not one-way and asynchronous, as in the Mturk samples.

Summary and policy advice

The prevalence of remote work and online collaboration calls for leaders who can lead remotely and communicate efficiently. The evidence shows that leadership based on rewards and punishment is effective but that this type of motivation has its limits. Communication elements that signal charisma, on the other hand, can be effective even in purely remote settings such as the gig economy. Leaders must keep in mind that text-based or audio communication reduce non-verbal signals and the complexity of information sent; they must therefore adapt the chosen communication mode to the complexity of the message. If the message is simple, pure text-based communication is efficient, but if the message becomes more complex, a richer communication mode such as video messaging might work better. It is essential that leaders deliver a congruent picture, meaning that both verbal and non-verbal signals must match each other. If leaders do not use communication instruments carefully, there is a risk that they will not be perceived as genuine, resulting in lower follower performance.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [3], [4].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Petra Nieken