Elevator pitch

Employees are more willing to work and put effort in for an employer that genuinely promotes the greater good. Some are also willing to give up part of their compensation to contribute to a social cause they share. Being able to attract a motivated workforce is particularly important for the public sector, where performance is usually more difficult to measure, but this goal remains elusive. Paying people more or underlining the career opportunities (as opposed to the social aspects) associated with public sector jobs is instrumental in attracting a more productive workforce, while a proper selection process may mitigate the negative impact on intrinsic motivation.

Key findings

Pros

Employees work harder and are more motivated when their job is associated with a genuine social cause.

Some people are willing to give up part of their private compensation to contribute to the greater good.

Socially responsible firms are also more attractive to jobseekers.

Attracting a motivated workforce is particularly important for the public sector, where performance is more difficult to incentivize directly due to multiple objectives and an output that is usually harder to measure.

In the public sector, randomized controlled trials suggest that extrinsic incentives (pay, career options) can be useful to attract a productive workforce and do not necessarily crowd out intrinsic motivation to serve the public interest.

Cons

What represents a good cause may be subjective, and a good match in terms of mission between workers and their firm is crucial.

Corporate social responsibility can backfire if perceived as instrumental.

Attracting a motivated workforce can be challenging, and the public sector appears to have had limited success.

Highlighting the social aspects of a job in the public sector may not be an effective way to recruit motivated workers.

The evidence on workers’ motivation is growing but still limited, affecting the generalizability of study findings.

Author's main message

Organizations that support a social cause in a genuine way have an advantage in motivating employee effort. Jobseekers, customers, and investors view such companies as more attractive. The public sector, however, is generally not very successful in attracting motivated workers. Experimental studies show that using extrinsic incentives (better pay and career prospects) can be useful to recruit more productive workers in the public sector without necessarily having a negative effect on the intrinsic motivation to serve the public interest. This suggests that human resources practices from the private sector may also be useful in the public sector.

Motivation

Understanding what motivates workers is vital for enhancing productivity and designing effective compensation and retention policies. There is growing recognition that workers may be motivated to perform an activity even if they receive no apparent reward except the activity itself; that is, besides extrinsic rewards such as bonuses and promotions, intrinsic motivation also matters. In particular, a concern about the social cause pursued by the organization for which they work can be an important driver for workers.

This type of motivation is particularly important for employees in the public sector, who carry out critical tasks for the common good (e.g. in education, health care, and law enforcement) with multiple and sometimes conflicting objectives and whose output is usually difficult to measure. Outside of the public sector, the growing importance of not-for-profit and of corporate social responsibility practices among firms brings this type of motivation to the forefront. As summarized by The Economist in 2008, referring to a survey of corporate executives, “Ask almost any large company about the business rationale for its [corporate social responsibility] efforts and you will be told that they help to motivate, attract, and retain staff.”

Discussion of pros and cons

Many companies display a concern for the “greater good.” For example, a survey of 250 leading US companies reveals that they contributed $26 billion in total charitable giving in 2018, equivalent to around 1% of pre-tax profits. Many of these companies encourage the active involvement of their workforce in these charitable activities, for instance by committing to match their employees’ donations or by establishing formal employee volunteer programs and supporting their employees’ volunteering activities through paid release time, company-wide days of service, or other means.

These donations of money and time by businesses and their workers are examples of corporate philanthropy. Many firms also engage in other corporate social responsibility activities, such as adhering to operations codes of conduct involving, for instance, labor standards or environmental protection beyond that mandated by law. However, these practices are not always perceived as commendable; for instance, they could be considered as inappropriate for a firm, reflecting some corporate governance issue, or, even worse, as bogus and hypocritical.

Are workers more productive in firms advocating corporate social responsibility?

Studies have documented that customers respond to products whose production and distribution processes conform to some ethical notion (such as fairness or environmental sustainability). Examples include the willingness to pay more for organic cotton garments or for goods whose producers agree to donate part of the proceeds to charity. There is also some evidence that investors’ decisions are affected by ethical criteria (e.g. refraining from investing in companies involved in producing alcohol and tobacco, and in gaming).

What about one of the most important assets of any company, its employees? Does knowing that the organization they work for is concerned with the greater good motivate them to put more effort into what they do? Do socially responsible firms have an advantage in the recruitment of talents? Or are corporate social responsibility activities perceived merely as a public relations stunt or as “green washing?” Companies concerned with the greater good may be also different in several other dimensions, such as working conditions, career prospects, market success, and prestige, dimensions that are difficult or impossible to control for, so just looking at existing companies is not going to answer these questions.

To establish convincingly whether workers are motivated by the greater good, many studies have used the methodology of experimental economics. Experimental studies have the advantage of determining causal effects in a credible and precise way—in this case, the impact on productivity from linking a job to the greater good. Convincing evidence would be very difficult to attain using observational data because people self-select into different types of jobs and their job preferences may be correlated with some other characteristics that affect their productivity but are difficult to account for. Moreover, quantifying and comparing output across jobs may prove very challenging. Experiments solve these issues by designing easy-to-quantify tasks and randomly allocating participants into different environments.

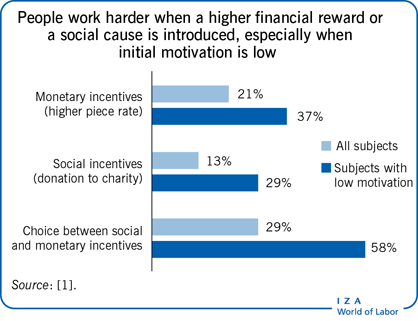

One study sets up an online experiment on boosting productivity among more than 300 subjects working remotely for four hours at a data entry task [1]. The study compares the effectiveness of financial incentives (in the form of a piece rate) and social incentives (in the form of a charitable donation) for boosting productivity. Not surprisingly, the study finds that subjects are sensitive to the strength of financial incentives; they work harder when the piece rate is higher. Introducing a charitable donation is also effective in boosting productivity: individual performance (entries per hour) improves 13% on average (see the Illustration).

However, whether the charitable donation is linked to productivity through a “charity piece rate” or whether it is a lump sum does not matter for productivity [1]. Neither does the amount transferred to the charity. In so far as a donation to a charity is included in the compensation package, subjects respond by increasing their effort, but they do not respond to the strength of the social incentive. Moreover, the effects of both financial and social incentives are concentrated among subjects initially lacking in motivation to perform the task. Individuals with low initial productivity respond very strongly to the introduction of a charitable donation, increasing their productivity by almost 30%. The presence of social incentives seems to enhance a worker's identification with the job, providing some meaning to what would otherwise be just a repetitive task.

So, subjects respond when social incentives are introduced, but would they be willing to sacrifice some of their private compensation to benefit a charitable cause? When given the opportunity, half of the subjects in the study do so, with women more likely to do so than men [1]. Comparing the different compensation schemes from the point of view of a firm reveals that engaging in corporate philanthropy increases productivity by less than an equally costly increase in private compensation, but the difference is small. Taking into account the other benefits related to corporate social responsibility (including the impact on customers and investors, plus potential tax benefits), it could be contended that corporate philanthropy may be more effective than financial incentives. Also, giving subjects the opportunity to choose whether to include a charitable donation in their compensation package is the most effective way to increase performance.

The positive impact of social incentives on motivation has been corroborated by other experimental studies. For instance, a large real effort experiment on the online platform MTurk has recently compared different incentives, including donations to a charity [2]. The results confirm a significant impact on performance, with a lack of sensitivity to the exact amount, so that 1-cent and 10-cent donation piece rates have the same impact. The results also show less effectiveness compared to private incentives, so that a 1-cent donation piece rate increases performance less than a 1-cent private piece rate, albeit donations outperform other behavioral interventions that are popular in the human resources literature based on social comparison, ranking, and task significance.

An important aspect is a good match between workers and a firm's mission. A study took advantage of the 2012 presidential election in the US to recruit participants to work for one of the two major candidates (Barack Obama, a Democrat, or Mitt Romney, a Republican), filling and addressing envelopes containing letters to independent voters [3]. After measuring participants’ political preferences a few weeks before the experiment, the study randomly assigned participants to work for either the Republican Party or the Democratic Party campaigns. Workers’ preferences were aligned with their jobs when Republicans were assigned to work for the Republican campaign and Democrats for the Democratic campaign, and misaligned when workers were assigned to work for the opposite campaign. The experimenters also varied financial incentives, either paying a flat wage for the job or adding a supplement contingent on the number of letters completed.

The study finds that matching preferences has a very strong impact on productivity: output is 72% higher when preferences are aligned compared with mismatches. Financial incentives also work: adding performance-contingent pay boosts output by 35% compared with offering just a flat wage. It is interesting to note that the effect of financial incentives is strong in the case of mismatches, while it is rather muted when employer mission and employee preferences are aligned. These findings suggest that financial incentives can partly compensate for misalignment, but, of course, they are expensive.

Experimental studies thus underline how “doing good” is a powerful motivational driver for workers, but that what “doing good” means may be subjective. To maximize productivity, it is important that workers’ preferences align with the mission pursued by the organization.

Beyond productivity, prosocial incentives can have an important effect on job satisfaction, as found in a field experiment with airline captains testing the effect of four distinct management practices, including a donation to a charity conditional on achieving certain targets [4]. Also, there may be benefits in terms of attracting talent. A recent field experiment compares the effect of corporate social responsibility and financial incentives on hiring and motivating workers for a data entry job [5]. In this setting, corporate social responsibility was a notice about the firm charging at cost non-profit clients engaged in good causes. The study finds that corporate social responsibility has a strong impact on application rates, also improving the quality of applicants in terms of their baseline productivity and accuracy, thus reducing per-unit production costs. The estimates of the benefits are such that, given the type of job, a US$1m corporate social responsibility annual expense would be profitable for a firm with 411 workers or more.

There are also possible drawbacks of corporate social responsibility. A field experiment hiring people on MTurk to perform a short transcription task found that corporate social responsibility, again in the form of donations to charity, increases employee misbehavior, in that more people take the opportunity to shirk by getting part of the payment without actually performing the task or falsely claiming text to be illegible [6]. The finding is consistent with moral licensing, so that “doing good” in one domain frees people to behave unethically in another domain. Also, charitable incentives may backfire if used instrumentally in order to profit the firm, in that their use may actually worsen the perception of the firm. There is indeed growing evidence about the strategic use of corporate philanthropy that can become in reality a lobbying activity, as shown in a recent work that analyzes grants made by philanthropic foundations associated with Fortune 500 and S&P 500 corporations, which estimates that 7% of total US corporate charitable giving is politically motivated [7].

There is therefore a risk that corporate social responsibility may become the victim of its own success, if it starts to be perceived as just another device in the managerial toolbox and, therefore, fails to provide meaning to the job and to convey a credible signal about the true intentions of the employer.

Is the public sector attracting motivated workers?

The evidence presented so far suggests that pursuing the greater good can be an important motivational driver for at least some workers. What about workers in the public sector? In a well-functioning democratic society, the public sector should, by definition, pursue objectives that aim to achieve the greater good and so should be well positioned to attract a workforce that is sensitive to this type of motivation. Moreover, agency problems are arguably more serious in the public sector than in the private sector, because public organizations pursue multiple objectives and have many different stakeholders, some with divergent interests. Output and performance can thus be very challenging to measure in sectors like education, health care, law enforcement, and public administration, because they lack a monetary measure such as revenues or profits and quality is inherently difficult to quantify.

These characteristics of the public sector make it particularly prone to corruption, regulatory capture, and waste. Having a motivated workforce can act as an important antidote against such negative outcomes. Finally, and partly for the reasons highlighted above, extrinsic incentives like bonuses or the threat of firing are less common in the public sector, making intrinsic motivation more prominent. It is important, then, to understand whether the public sector is able to attract a particularly motivated workforce and what strategies can be put in place to achieve such a goal.

A common methodology to assess whether public sector workers are intrinsically motivated to serve the public interest in carrying out their jobs—whether they have a public service motivation—is to compare private and public sector workers along some dimension of prosocial behavior. For instance, are public sector workers more likely than their private sector counterparts to donate to charities, to volunteer, to give blood? Several studies have answered this question affirmatively, at least for a subset of public sector employees.

A study published in 2019, for instance, finds that applicants to the police force in Germany are more trustworthy and more willing to enforce norms than a comparable control group [8]. A study in the Netherlands from 2012 looks at what people choose as a reward for completing a survey, where the options are a gift certificate, a lottery ticket, or a charitable donation [9]. Focusing on workers at the start of their career, the study finds that those in the public sector are more likely to choose the charity than those in the private sector. As tenure increases, however, the difference disappears and even reverses. This is partly explained by the fact that public sector employees feel that they have already contributed to society by working at a public sector job that they believe underpays them.

Indeed, one issue with several studies comparing private and public sector workers is that the types of jobs may be inherently different in the two sectors, which could have an impact on the behavior that is used as a proxy for public service motivation. As an example, a nurse (working in the public sector) may have plenty of opportunities to behave altruistically on the job and thus may not differ much from other workers in her prosocial activities out of work, even if he or she is genuinely more altruistically motivated. The same issue arises for other characteristics that may differ between jobs in the public and private sectors and that may be difficult to control for (such as required effort, career incentives, and job security).

To overcome these difficulties, a 2014 study uses a representative survey in 12 European countries of individuals who are at least 50 years old to look at whether public and private sector workers differ in their propensity to volunteer for a charity [10]. Crucially, this study also looks at people's behavior after retirement, where differences in working conditions no longer exist. The finding is that former public sector workers are indeed more likely to volunteer than are former private sector workers, but this finding is entirely explained by differences in the workforce composition of the two sectors. On average, public sector workers are more educated and employed in more skill-intensive occupations, characteristics that are associated with a higher propensity to volunteer. Once these two factors are accounted for, there is no difference in propensity to volunteer between the two sectors. Disaggregating the data across the main occupations in the public sector confirms the overall picture for public administration and health and social work; for education, however, former public sector employees are more likely to volunteer even after controlling for a rich set of characteristics. Disaggregating the data across countries confirms the overall picture for most of them, although in some countries the positive differential between public and private sector employees in volunteering persists even after controlling for differences in workforce characteristics.

What can be done to improve recruitment in the public sector?

All in all, the evidence suggests that the public sector as a whole may not be very successful in attracting particularly motivated employees. Given the crucial role of public service motivation emphasized above, it is important to learn what can be done to improve the selection of the workforce for the public sector. In recent years, several randomized controlled trials (RCT) have explored different aspects of the workforce selection process for the public sector. These studies took place in low- or middle-income countries, but their findings can also be instructive for more advanced economies, despite the fact that the structure of the labor market, in particular the role of the private sector, can be quite different.

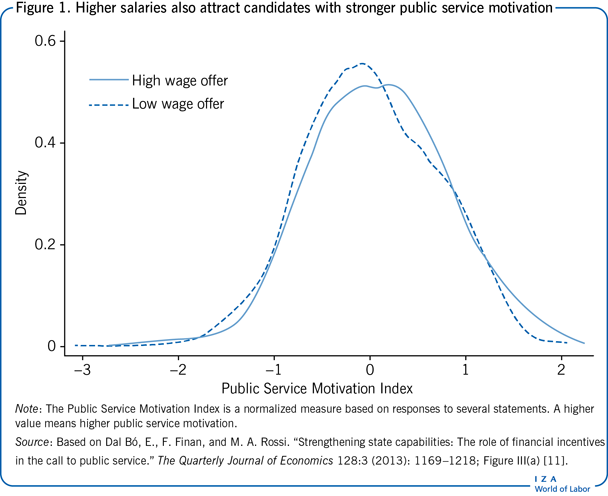

An organization could offer higher salaries to attract better people. For the public sector, however, there is a concern that high salaries may be counterproductive, as they may attract people without high intrinsic motivation to work in the sector (people lacking public service motivation). A 2013 study addresses this issue in a credible way by exploiting a 2011 recruitment drive for public sector positions in Mexico [11]. The drive to recruit community development agents took place across 106 recruitment sites, with salaries randomly assigned across sites. In some localities, the posted wage was 5,000 Mexican pesos a month (approximately US$500 at the time), corresponding to the 80th percentile of the wage distribution for the population in those localities. In other localities, the posted wage was much lower, at 3,750 pesos per month.

A great deal of information is available about the candidates: earnings in other jobs, measures of raw cognitive ability (IQ), and market skills (such as computer use and years of schooling), as well as standard measures of personality traits and public service motivation. The main finding is that higher wages attract better candidates, as measured by quality—candidates with higher earnings in other jobs, a better occupational profile (in terms of experience and white-collar background), higher IQ, and preferable personality traits. Higher salaries also attract candidates with stronger public service motivation (Figure 1), suggesting that higher salaries do not crowd out motivation.

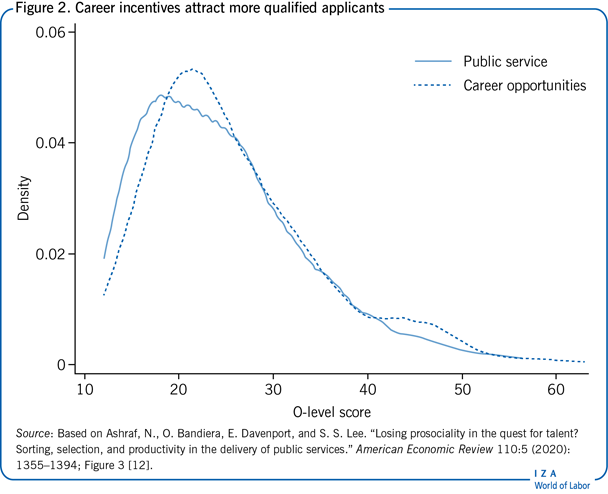

Another way to attract motivated workers to the public sector might be to underline the social dimension of public service, a mechanism explored by an RCT that took place in 2010, when Zambia created a new civil service cadre called the Community Health Assistant [12]. The main task was visiting households to provide health care services in underserved areas. The roughly 330 newly created positions were advertised through recruitment posters in public spaces across 48 districts. In half of the districts, which were randomly selected, the poster advertised the career opportunities associated with the position (“Become a community health worker to gain skills and boost your career!”), while in the other half the advertisement had more of a public service emphasis (“Want to serve your community? Become a community health worker!”).

A first finding is that the message matters: in districts with posters highlighting career incentives, candidates were on average more qualified, as measured by their high school results (Figure 2). This suggests that emphasizing career incentives was instrumental in attracting a pool of qualified applicants who would not have applied otherwise. The average applicant when emphasizing career incentives was, at the same time, also less prosocial. The selection process, however, was such that recruits at the end had the same high level of prosociality across the two treatments, while those treated with the career message were more talented. This study also tracks the activities of the newly recruited community health assistants over a period of 18 months and finds that personnel recruited through the career incentives pitch performed better, both in terms of providing more inputs (e.g. household visits), as well as improving health practices and outcomes (e.g. share of underweight children).

As in the Mexico study [11], extrinsic incentives (in this case career opportunities) enable the recruitment of better-performing candidates. This is, however, not the case for an experiment conducted in Uganda in 2012 to recruit health-promoters [13]. Manipulating expected earnings, the experiment shows how higher financial incentives attract more applications but discourage those with strong prosocial preferences. Other studies look at students and their interest in public service jobs. A study in India measures the propensity to cheat among 669 final-year college students in the city of Bangalore using a dice game [14]. It also measures pro-sociality using a dictator game, in which a student allocates a sum between themselves and another recipient. The authors find that students who cheat are 6.3% more likely to want a government job and also that more generous students in the dictator game prefer private sector jobs over government jobs. Then, using a sample of 165 public health nurses, the study finds that the measure of cheating based on the dice game is correlated with actual corrupt behavior among these public sector workers, in this case fraudulent absenteeism from work. The study thus finds evidence of negative selection into public sector jobs in India. A 2014 study with Danish students, however, finds the opposite result, documenting strong self-selection of more honest individuals into public service [15].

Limitations and gaps

As underlined above, gathering sound evidence on workers’ motivation and its implications for productivity and other dimensions of job performance is subject to tough methodological challenges. Experimental methods (either laboratory experiments or RCT in the field) have been used to address some of these challenges. To be credible, findings from laboratory experiments need to be complemented by evidence from the field, but there have been only a few RCT, because their implementation can be very demanding. As a result, the evidence on workers’ motivation is still rather limited, which affects the generalizability of the study findings. For instance, it is questionable how much evidence gathered from Zambia can guide policy in Germany. This challenge is particularly relevant for employment in the public sector, as the role of the public sector can be very different in different countries. The contrasting results between India [14] and Denmark [15] in terms of honesty and selection into public service point at this. Evidence on important aspects of motivation—for instance, its psychological determinants and how it evolves over the career of individuals—is also scarce. This limited knowledge can nonetheless provide some useful guidance to policy.

Summary and policy advice

In the private sector, promoting a worthwhile social cause can be an important tool for motivating an organization's workforce (and its customers and investors). This is an element in favor of corporate philanthropy or other forms of corporate social responsibility in the private sector. If such practices are deemed beneficial for society as a whole, they should be actively promoted. One way to put this issue at the forefront would be to require companies to report on social and environmental matters, as mandated in the UK 2006 Companies Act for public companies.

Workers’ motivation is particularly important in the public sector, and appropriate policies should be in place to attract and retain the right types of workers. The evidence on specific policy measures is growing but still sparse, and there may also be significant variation across professions, a person's income level, or other factors. Because of this, a rigorous evaluation of the impact of new policies would be desirable. This would generate stronger evidence on which to base further policy interventions. In particular, human resources practices developed in the private sector could represent an important source of inspiration, as the evidence indicates that extrinsic incentives do not appear to necessarily crowd out intrinsic motivation.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors, as well as Michael Vlassopoulos, for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article describes an additional “Con” in which corporate social responsibility can backfire if perceived as simply for the profit of the firm, includes a new Figure 2, and discusses the most recent evidence on the topic, updating the “Key references.”

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Mirco Tonin